Sommaire

Pagination de l'dition papier

Guide

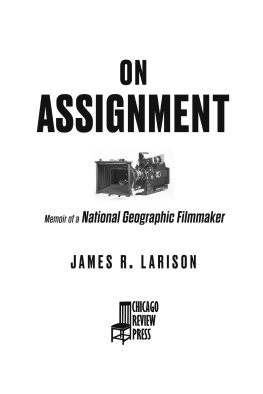

Copyright 2022 by James R. Larison

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-64160-523-6

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021942406

Typesetting: Nord Compo

Unless otherwise indicated, all images are from the authors collection

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

In memory of a brilliant, thoughtful friend

taken from us too soon.

Donald M. Cooper

Associate Director and Acting Director

Educational Films Division

National Geographic Society

AUTHORS NOTE

THIS MEMOIR SPANS MORE THAN sixty years. To make it more readable, I have taken the liberty of collapsing time and occasionally bringing events that may have happened at separate locations together for the sake of clarity and brevity. Otherwise, this memoir captures events and people as best I can remember them.

I have changed and omitted some names to protect people and their privacy.

I make no apologies for my defense of nature, wildlife, and intact healthy ecosystems. I am an ecologist. I believe the future of the entire planetary biological system, which includes human beings, depends on the preservation and conservation of wild lands and wildlife.

I hope this book will inspire its readers to look to nature for peace of mind.

PROLOGUE

ONE INCH AT A TIME, I crawled on my belly into an underground cave cradling my Arriflex motion picture camera. There was not enough head room in the cave to turn over let alone sit up. Snakesthousands of themcarpeted the cave floor. The only sound came from the snakes themselves as countless individuals slid over top of one another in a continual roiling mass of writhing, scale-covered bodies. The snakes had no interest in me. The males were trying to mate with the females. The females were trying to escape the craziness. I was just trying not to panic. Gently, I pushed the snakes to the side as I struggled to move deeper into the dark. But the snakes were implacable, and soon they began crawling over top of me, through my clothes, and under my armpits. I could feel an especially big one starting up the inside of my left pant leg headedwho knows where. The deeper I went into the cave, the more the walls and snakes seemed to close in on me. I was on the verge of a full-blown panic attack, but if I panicked and had to suddenly get out, I would have had to shimmy feetfirst, back the way I came in.

You might ask, what was a person who harbors an irrational fear of snakes and another, perhaps not-so-irrational, fear of closed-in spaces doing in a tiny cave in springtime when snakes like to breed by the tens of thousands in these tight underground spaces?

That would be a good question. Many of the things I did in those days a normal person might consider reckless, but I did them because I cared more about the footage I might obtain and the film I wanted to make than I did about the panic welling up inside of me. I came to film red-sided garter snakes coming out of hibernation for the National Geographic Society, and I was not going to leave until I got that footage, no matter how many snakes crawled inside my pants.

For nearly two decades, my wife Elaine and I worked for the Television and Educational Films Division of the National Geographic Society. It was the best job in the world, even when underground in a snake pit. Every assignmentand there were nearly one hundred of themcame with its own set of challenges. Underground in a snake pit in Manitoba one day, and not a year later, I was in a frozen northern Wisconsin lake photographing a mud minnow that breathed air from tiny bubbles trapped on the underside of a sheet of ice two feet thick. Other times, Elaine and I would willingly strap ourselves to the side of a mountain with an eleven-millimeter rope affixed to a single ice screw, a thousand feet of mostly air beneath our feet. Then, before you knew it, we would be bathing in the warm waters of the South Pacific with a two-thousand pound, twenty-foot manta ray gliding silently overhead.

We went to these places and we did these things because we wanted to share our love of wilderness with others. I thought if I could just show enough people what was out there, if I could use my skill as a filmmaker to capture the essence of wilderness, if I could make others feel nature the way I felt it, they too would believe in the importance of wild places. They too would want to save as much wilderness as possible. Yes, there were risks and there were challenges, but these were the choices Elaine and I had to make every day of our lives, just to do this spectacularly rewarding job.

In a continual struggle to maintain a reasonably normal family life, we took our two young sons with us most everywhere we went. John and Ted spent two years on a desert mountain in eastern Oregon, six months snorkeling on the Great Barrier Reef, and most of one summer living with bears in Alaska. They learned to scuba dive in Palau, map the stars in the sky above Bora-Bora, and climb ice on Athabasca Glacier in Alberta.

Not surprisingly, when they came home from one of their many long trips, our sons wanted to share their experiences with classmates. One time we got a call from our oldest sons teacher, who told Elaine we needed to do something about our son telling such tall tales. So, what exactly did John say? Elaine respectfully asked. The teacher repeated Johns story about a blue-ringed octopusone of the most poisonous animals in the worldcoming to within a few inches of his dive mask. Elaine simply asked, Did you ever consider that he might be telling the truth?

Our lives were different, always challenging, and often dangerous. A lot of people have had trouble wrapping their minds around what we did; a few of my best friends have even told me I was crazy to dive with man-eating sharks, hang on the outside of helicopters, and climb vertical ice, but when I look back at the break points in our lives, it occurs to me that we never really considered any other options. We wanted so badly to do this job and make a difference in the struggle to preserve the environment. For us, there was only one choice, to eagerly accept that next assignment and break our own trail in pursuit of those priceless National Geographic images, and to tell the story of wilderness.

PART I

COMING INTO THE WILD

LAKE TIMAGAMI

WITH LITTLE MORE than a seventeen-foot wood-and-canvas canoe, two paddles, and a youthful certainty that all would end well, we launched our marriage from a gravel bar at the eastern end of Lake Timagami (now Temagami) and cut our own path into a largely undisturbed Canadian wilderness. It was the summer of 1967, and Elaine and I were on our honeymoon, just two eighteen-year-old kids with vivid dreams and insufficient experience. Elaine took the bow of our canoe, using her paddle to set a four-count rhythm while I sat in the stern using a J-stroke to provide power and direction. Of course it couldnt last, but our lives began smoothly enough with our canoe gliding effortlessly across glassy, still, and deep waters. In those endlessly quiet moments, the wilderness spoke to us in a language of its own. As we listened, the bonds between the three of us grew, and I came to understand that one could do far worse than to build a marriage in a place of such beauty, harmony, and elegance.

Together, we slid across the mirrorlike surface of the lake, our own images reflecting back at us, everything tinted in a surreal golden glow. Each time Elaine would pull her paddle through the water and retrieve it in preparation for the next stroke, a glistening sheet of water would slide down the paddle blade and drain hypnotically back to the lake. Driven by a light cool breeze, a constant procession of parallel ripples slid across the watery expanse, each in its turn coming to lap gently against the bow of our Old Town canoe. The hollow slapping sound drifted away and came back seconds later as rhythmic echoes from a distant shore. It was peaceful and quiet and we were deliriously happy together.