A NOTE ABOUT THE COVER

Meanwhile word had spread around the island that money had come to these rocks. Merchants of every description could be seen struggling up the hill. And when they arrived, they spread the richest fabrics of India between the two humble huts. There were the finest brocades from Goudelour; there were handkerchiefs from Pulicat and Masulipatnam; there were muslins from Dacca that were in turn plain, stripy, embroidered and as transparent as daylight. There were fine white calicoes from Surat and rare chintzes of all colours, with green branches growing over sandy-coloured grounds. They unrolled the most gorgeous silks from China: white, grass green and dazzling red damasks; pink taffetas; armfuls of satin; pekins as soft as cashmere wool; white and yellow nankeens; and even some loincloths from Madagascar.

When Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierres novel Paul et Virginie was first published in 1788 it gained little attention, but as France moved towards revolution, it became increasingly popular. It tells the story of two children born of French parents in Mauritius: their mothers (one a widow, one a single mother) become friends, and the children grow up unencumbered by the rules of civilisation. But, as they reach puberty and their innocent love becomes more self-conscious, Virginia is invited to Paris to stay with a wealthy relative who wants to adopt her. Shes homesick, but when she finally returns to Paul theres a storm at sea. Unwilling to remove her clothes and reveal her nakedness, she drowns.

That last is the most dramatic of many key images tied explicitly to fabric. The story is directly modelled on the biblical tale of Adam and Eve, in which the moment when the protagonists lose their innocence and are cast into this brutal world is also the moment when they realise they have no clothes, and so they cover themselves.

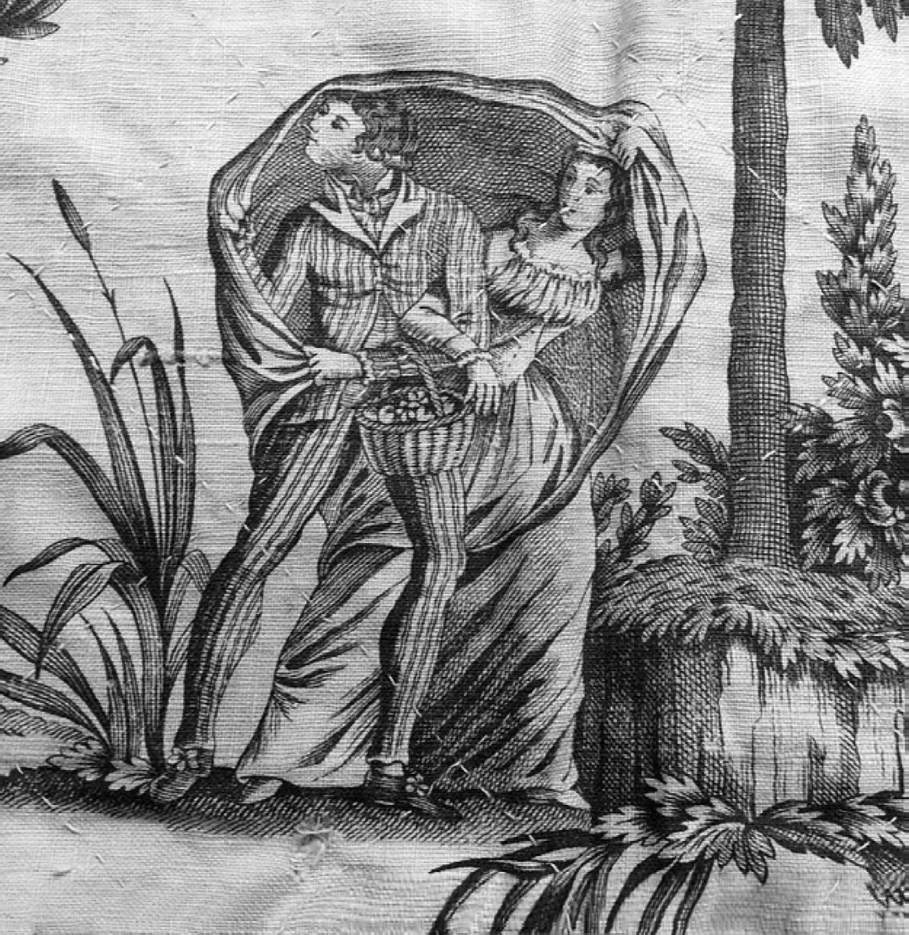

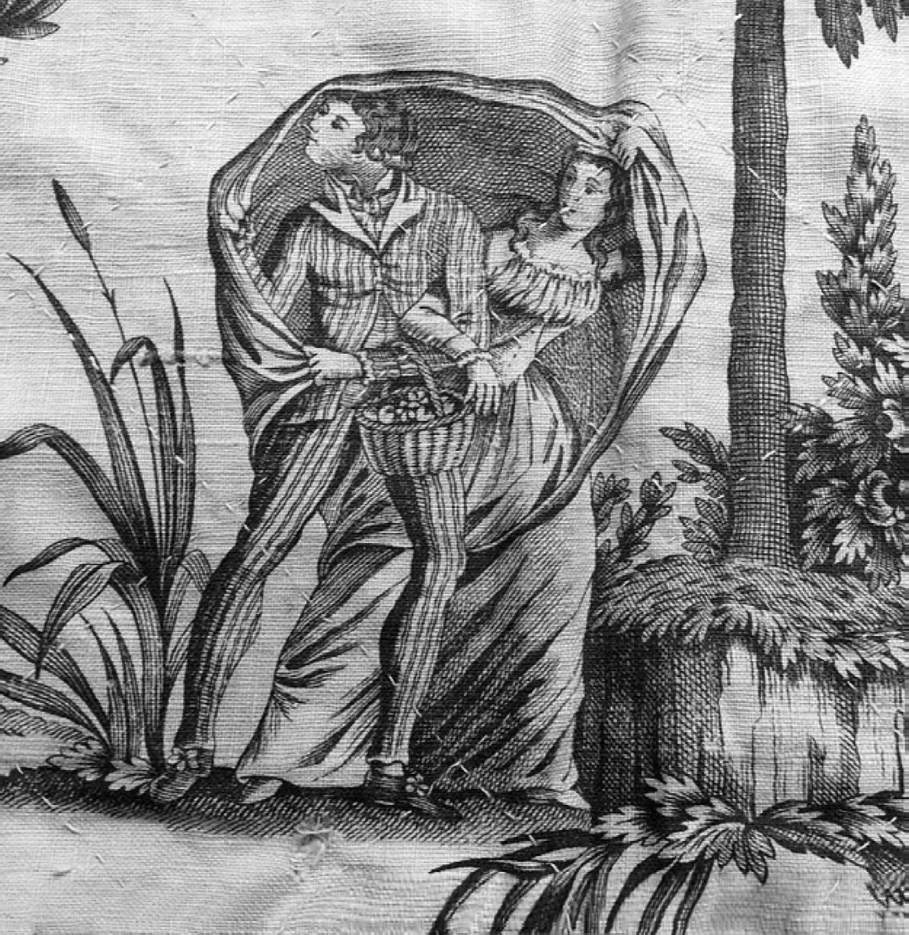

They were laughing fit to burst at being sheltered under an umbrella of their own making. Paul and Virginia made into upholstery fabric in France in around 1800.

So, in the book, the two mothers support their families by spinning cotton, the phrase while Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the Gentleman?, having been a call to revolution since at least the fourteenth century. And when the children get lost in the forest after trying to help a runaway slave woman, Paul covers Virginia with leaves to keep her warm. When Virginia is preparing for her journey to Paris, the textile merchants of the island visit her home, and spread out their wares as recounted above because it is only with fine clothing that shell be able to participate in the rigid (and ultimately morally destructive) life in the capital.

Saint-Pierre was a friend of the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The two men shared not only a love of nature, but also a belief that natural laws are the only ones by which we should live, and that so-called civilisation can only destroy us.

Napoleon Bonaparte kept a copy under his pillow during the Italian campaign in 1796. Or at least thats what he told Saint-Pierre. He told Thomas Paine exactly the same thing about his book, Rights of Man, so perhaps it was a habit of his to flatter in that way. Certainly, the deposed emperor was recorded as reading Paul et Virginie many times in Saint Helena, after he was exiled there in 1815.

The book was a sensation throughout the early nineteenth century in many European countries and in America. There were Paul and Virginia coffee cups and dinner plates and upholstery fabrics (of which this piece from the Victoria & Albert collection is an example, printed on calico around 1800 by Favre, Petitpierre et Cie of Nantes, originally with a crimson madder dye). There was even a Virginia haircut. It was like an older version of the kind of merchandising we now get for Harry Potter, except that all the items were meant for adults.

The scene on the cover of this book shows another turning point connected with fabric. It is told by the narrator, now an old man, who had once been a friend to both families.

One day, when I was coming down from the top of the mountain, I saw Virginia at the end of the garden. She was running towards the house under her petticoat, which shed lifted over her head to protect herself from a shower of rain. From a distance I thought she was alone, but when I got closer to help, I saw that she and Paul were arm in arm, and that both of them were almost entirely hidden under the same covering. They were laughing fit to burst at being sheltered under an umbrella of their own making. Those two lovely heads in the midst of that billowing petticoat made me think of the twin children of Leda, nestling inside the same eggshell.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Part way through writing this book I went to lunch with friends. I was recounting how Fabric had started out being just about fabrics but that it had turned and changed, almost by its own will, into a book about fabrics and grief. Oh! said someone further down the table. I do love grief! We looked at her in astonishment, until we realised that shed misheard, and had thought Id said Greece.

But this book did turn and change, and it did so almost by its own will, and it did take a long time, so Id like to thank my commissioning editor Rebecca Gray and her colleagues at Profile Books, especially Penny Daniel, Cecily Gayford and Calah Singleton, first for having the idea to ask me to write it and later the forbearance to wait for it to arrive. Also my agent Simon Trewin for helping at the critical contract moments and writing me encouraging postcards when I needed them most. And Susanne Hillen, for a brilliant and careful copy-edit, both delicate and precise. And most of all my editor Shan Vahidy, for cutting and tailoring the first, long manuscript so sensitively. And for writing comments in the margins that made me laugh aloud.

Many, many other people have helped. They include: Tim Aldred of Carloway Mill in Lewis; Mark Atkin and Bruce Mitchell who gave advice about PNG; Andrew Baker in Brisbane for sending catalogues; Roya and Brian Boustridge; Paul and Nicky Bray for deciding to keep pedigree Ryelands, and putting them in a field on my walk just when I needed them to be there; Clare Brown, machine interpretation supervisor at the National Trusts cotton mill museum at Quarry Bank in Manchester for checking the weaving and spinning bits; Malcolm Butler for the beer on the train, and the anecdote about jute; Mariel Carr and Annabel Pinkney from the Science History Institute in Philadelphia for their help with the stills from Bob Gores oral history video; Pamela Christie at PNG Trekking Adventures who introduced me to Florence Bunari; Dekila Chungyalpa, who reminded me about the khadags; Rosie Collins for those wonderful maps; Teresa Coleman of Teresa Coleman Fine Art in Hong Kong, who let me use her pictures of the long pao dragon robe; Mike Even, my friend in New England, for telling me about the snow; my brother, Nick Finlay, for trusting me to do this right; Serena Frascon at Maya Traditions Foundation for checking my account of backstrap weaving; Jan Hasselberg who told me more about tattoos in Papua New Guinea; Clarice Hui for giving access to the Hong Kong Polytechnic University library; Jen Jones, owner of Ada Joness patchwork quilt, which started me on this journey, and her colleague Hazel Newman who helped with the details; Ketkan Kumphuang in the library at the Queen Sirikit Museum of Textiles in Bangkok, who let me keep reading until the last moment despite a secret and unscheduled visit to the compound by a member of the royal family; Ian Lawson, Frances Lennard; Margaret Lewis, curator at the Allhallows Museum in Honiton, Devon; Edna Longley; Michael Longley, who not only gave permission for me to use his poem The Design as the epigraph to this book, but recited it to me on a coach, driving between World War I battlefields in northern France; Maria de Los Angeles Gimenez in St Gallen; Fachruddin Mangunjaya for the Bahasa origins of the word gingham; Katia Marsh for being my companion and photographer in Papua New Guinea and elsewhere; Andy Mills for spending a whole day talking tapa; Mark Miodownile; Nell Nelson for being my Scottish friend; Mel Ruth Oakley, curator at Verdant Works, for checking the jute section; Anna Ploszajski for reading through the science; Helen Peden (and colleagues including Maddie Smith and Alexa McNaught-Reynolds) at the British Library for enabling my close examination of Alexander Shaws barkcloth book when it was out for conservation; Kari-Ann Pedersen at the Norwegian Museum of Cultural History; Ian Potts for the shirt; Gwynedd Roberts for checking the lace section; Isabel Robertson in Melbourne for encouraging me, a complete stranger, to keep going with my PNG plans; Professor Neil Robertson; Erin Rodgers at Kew; Rabbi Daniel Sperber and Phyllis Magnus, for checking the Hebrew; Hilary Stevens for giving me a demonstration of hand-spinning in her garden, with the alpacas peering over the fence; David Suddens (and Zara, Ruud, Marjo, Jana and Cor) for arranging such a splendid day at Vlisco; Marci Tate Davis at the High Museum; Dr Barry Teperman and his colleagues from No Roads Expeditions for giving me antibiotics when I needed them; Taqadus Wani; David Weir for hunting out obscure references at Paisley Library; Mary Ann Wise of Multicolores in Guatemala; John Wooding of H. Huntsman & Sons in Savile Row; Helen Wyld at the National Museums of Scotland for help about Janet Gothskirks tunic. And everyone working at