Victoria Finlay - Jewels: a secret history

Here you can read online Victoria Finlay - Jewels: a secret history full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York, year: 2006, publisher: Ballantine Books, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Jewels: a secret history

- Author:

- Publisher:Ballantine Books

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- City:New York

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jewels: a secret history: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Jewels: a secret history" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jewels: a secret history — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Jewels: a secret history" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Contents

For Martin

And for Patrick, my father.

Please stay with us a little longer.

Authors Note

11 110

In 1802 the wealthy Viennese banker Jacob Friedrich van der Nll bought up eleven of Europes top mineral collections, and decided he wanted them to be cataloged and classified. He selected a young German mineralogist called Friedrich Mohs, whose only serious work experience to date had been as a pit foreman in the Neudorf silver mines. Mohs wrote ample notes on the different stones brittleness, specific gravity, magnetism, electricity, taste, odor, and hardness. The most difficult one to measure was hardness. He puzzled for a long time about how he could quantify how much harder a lump of topaz is than a nugget of gold, or how much harder a diamond is than everything else.

Mohs genius lay in realizing that he had been approaching the problem from the wrong direction. Instead of finding a way of determining the absolute hardness of minerals, he decided to develop a comparative scale instead. So he chose ten minerals of which every preceding one is scratched by that which follows it, and gave them each a number according to his new scratching order. The softest was talc, which scored one, while the hardest was diamond, which therefore got ten. Everything else came somewhere in the middle. Glass turned out to have a value of just over five, and Mohs soon discovered that the so-called organic gemstones, including jet, pearl, and amber, were always softer than glass, while most mineral gems were harder. He acknowledged that the values were arbitrary, diamond at ten being several times harder than rubies at nine, but the system was at least easy to use. You can do it at home: anything that can be scratched by a fingernail is below two; anything that takes a mark from a pocketknife blade is below five; anything that can scratch quartz is above seven. Even today Mohs scale is an important element in gem classification. It is the logic behind the organization of this book, and it is also a useful thing to know before choosing a gemstone. Diamonds, rubies, and sapphires are extremely durable and therefore good for rings; emeralds at eight are a little softer, while amber at around 2.5 will easily lose its polish and is usually better as earrings or a necklace or part of a glittering imperial wall panel.

Preface

BEGINNING THE SEARCH

I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the sea shore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.

SIR ISAAC NEWTON

Im not suggesting we stop analyzing stones, but am just proposing a better balance. The heart of our product is its beauty and the romance surrounding it. Todays gemmology is too often a heartless shell. We are selling illusion. We need to become conjurors.

RICHARD HUGHES

When traditional Russian icon painters begin work on a new piece, they start by covering a simple wooden panel with a mixture of chalk and glue. The whiteness will shine out from the finished painting, representing the purity of the human soul. Then they give their saints shape and color, using paints made of traditional materialsbright blue from Afghan mines, pale green from corroded copper, deep red from Spanish mercury. Then, if the icon is a special one, they cover most of the picture with gold, often leaving only the saints face to peer out of a little window. And the final step, if it is a very special icon indeed, is to set precious stones around it. They do this because, while the paint represents the earth, the jewels are the symbols of heaven.

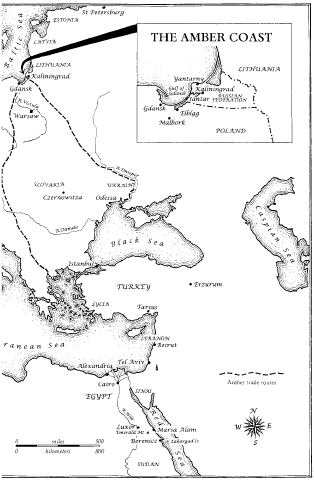

My first book was inspired by those paint materials: the twigs, stones, and beetles that are the raw materials of human art. But as I was researching it I often heard stories about jewelsthose other, more famous, sources of color. I heard of how people were once hanged for picking up amber pebbles from the beaches of northern Europe; how the deepest color for black was named after a rare jewel formed by the same process as coal; how Christopher Columbus was thrown into prison for not admitting to his royal sponsors that he had found pearls; and, perhaps most extraordinary of all, I heard how, with recent discoveries of how to make gem-quality diamonds in laboratories, the market for the most precious stones is tottering on the edge of change.

And then I was given a ring. It is an engagement ring, and its three small square stonesone pale green, like chewing gum; one dark green, like a sea-worn bottle; and one deep red, like a smooth brickare made of glass. They dont have a carat value like most jewels but they do have a wonderful story. They are eight hundred years old, and they were scraped from a wall almost eighty years ago, by a boy who later became a bishop, in a place whose sacred beauty had affected the lives of entire empires.

Perhaps the greatest church in Christendom is the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, which was once Constantinople, the capital of Byzantine Christianity for many centuries. But in 1453 the Muslims captured the city, and the Hagia Sophia became a mosque. This was greatly resented by many people over the centuries, including one Christian boy who grew up there in the 1920s. He and his friends sometimes pretended to be Muslim and went up to the womens section in the gallery, put their hands behind their backs, and pretended to pray while they prized out the mosaic stones from the wall to sell to tourists in the marketplace. When this boy grew up he became a priest, then a metropolitan, or Orthodox bishop, and he forgot his childish mischief. But one day, some years ago when he was very old, he found his three last stones and gave them to my fianc. Later, when we decided to make them into an engagement ring, they became jewels in their own rightand a reminder to me of how the most precious thing about stones in a jewel box is not always their rarity, their size, or their perfection. It is their stories.

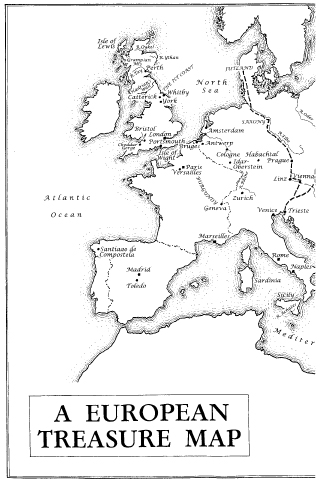

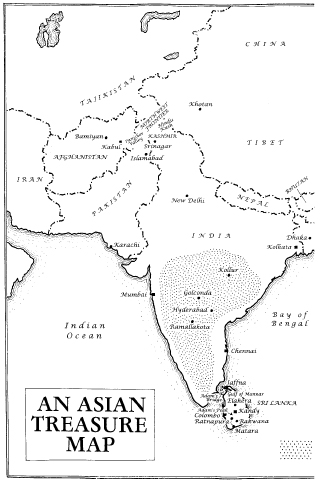

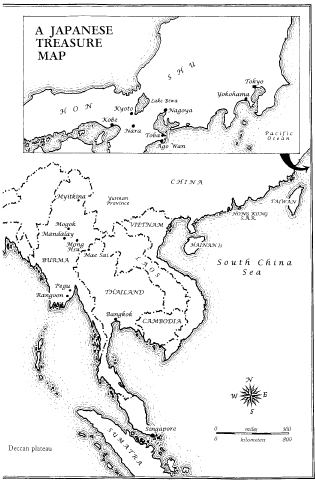

So, with my new ring on my finger, I set off on journeys to find themnot so much the gems as the stories behind them. The search took me to the greatest gem fair in the world; to the ancient City of Jewels in Sri Lanka; to Burma to visit the fabled ruby mines of Mogok; to the Japanese village where a young noodle-seller dreamed of growing pearls in oysters; to Antwerps busy diamond district; and to California, to meet a man whose father invented emeralds, and who himself has found a way to make perfect yellow diamonds.

This book is, mostly, written in praise of small things. There are a few boulders in its pages, but they are really just for show. Even the biggest jewels are mostly rather small: the word in English comes from the Old French for little joys and in gem terms the phrase hens egg usually means gigantic. The book is also, largely, a celebration of mineral things. Only jet, coral, and the creatures that reluctantly make up the insides of some rare pearls have ever been alive, while other prized stones, including amber, plant-opals, and ordinary pearls, have exuded and/or been extruded from living things. But most gems are crystals that have formed in the depths of the earth and emerged millionsor in one case hundredsof years later, with a beauty for which men and women have, on occasion, been prepared to commit theft, treason, torture, and murder.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Jewels: a secret history»

Look at similar books to Jewels: a secret history. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Jewels: a secret history and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.