How to Lie with Statistics

There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Disraeli

Statistical thinking will one day be as necessary for efficient citizenship as the ability to read and write.

H. G. Wells

It aint so much the things we dont know that get us in trouble. Its the things we know that aint so.

Artemus Ward

Round numbers are always false.

Samuel Johnson

I have a great subject [statistics] to write upon, but feel keenly my literary incapacity to make it easily intelligible without sacrificing accuracy and thoroughness.

Sir Francis Galton

More Praise for How To Lie with Statistics

"This puckish riff on how math can be manipulated is only 142 pages; most people could read it on a train ride or two, or in an afternoon at the beach. As light as the book is, however, it is nevertheless profound. In one short take after another, Huff picks apart the ways in which marketers use statistics, charts, graphics and other ways of presenting numbers to baffle and trick the public. The chapter 'How to Talk Back to a Statistic' is a brilliant step-by-step guide to figuring out how someone is trying to deceive you with data."

Wall Street Journal

"This department turns with pleasure to Darrell Huff's delightful How to Lie With Statistics. It is hard to think of a form of statistical skullduggery that he has not laid bare."

"The Business Bookshelf," New York Times

"Illustrator and author pool their considerable talents to provide light, lively reading and cartoon fare which will entertain, really inform, and take the wind out of many an overblown statistical sail."

Library Journal

"A timely tonic...This book needed to be written, and makes its points in an entertaining, highly readable manner."

Management Review

Also by Darrell Huff

HOW TO TAKE A CHANCE

with illustrations by Irving Geis

CYCLES IN YOUR LIFE

with illustrations by Anatol Kovarsky

THE COMPLETE HOW TO FIGURE IT

with illustrations by Carolyn R. Kinsey

How to Lie with Statistics

By

DARRELL HUFF

Illustrated by IRVING GEIS

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York London

To my wife

WITH GOOD REASON

Copyright 1954 by Darrell Huff and Irving Geis

Copyright renewed 1982 by Darrell Huff and Irving Geis

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huff, Darrell.

How to lie with statistics / by Darrell Huff: pictures by Irving Geis.

p. cm.

1. Statistics. I. Title

HA29.H82 1993

519.5dc20

93-28401

CIP

ISBN: 978-0-393-31072-6

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Contents

Acknowledgments

T HE PRETTY little instances of bumbling and chicanery with which this book is peppered have been gathered widely and not without assistance. Following an appeal of mine through the American Statistical Association, a number of professional statisticianswho, believe me, deplore the misuse of statistics as heartily as anyone alivesent me items from their own collections. These people, I guess, will be just as glad to remain nameless here. I found valuable specimens in a number of books too, primarily these: Business Statistics, by Martin A. Brumbaugh and Lester S. Kellogg; Gauging Public Opinion, by Hadley Cantril; Graphic Presentation, by Willard Cope Brinton; Practical Business Statistics, by Frederick E. Croxton and Dudley J. Cowden; Basic Statistics, by George Simpson and Fritz Kafka; and Elementary Statistical Methods, by Helen M. Walker.

Introduction

T HERES a mighty lot of crime around here, said my father-in-law a little while after he moved from Iowa to California. And so there wasin the newspaper he read. It is one that overlooks no crime in its own area and has been known to give more attention to an Iowa murder than was given by the principal daily in the region in which it took place.

My father-in-laws conclusion was statistical in an informal way. It was based on a sample, a remarkably biased one. Like many a more sophisticated statistic it was guilty of semiattachment: It assumed that newspaper space given to crime reporting is a measure of crime rate.

A few winters ago a dozen investigators independently reported figures on antihistamine pills. Each showed that a considerable percentage of colds cleared up after treatment. A great fuss ensued, at least in the advertisements, and a medical-product boom was on. It was based on an eternally springing hope and also on a curious refusal to look past the statistics to a fact that has been known for a long time. As Henry G. Felsen, a humorist and no medical authority, pointed out quite a while ago, proper treatment will cure a cold in seven days, but left to itself a cold will hang on for a week.

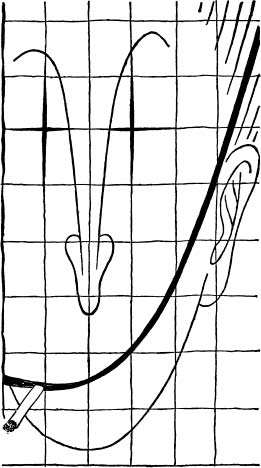

So it is with much that you read and hear. Averages and relationships and trends and graphs are not always what they seem. There may be more in them than meets the eye, and there may be a good deal less.

The secret language of statistics, so appealing in a fact-minded culture, is employed to sensationalize, inflate, confuse, and oversimplify. Statistical methods and statistical terms are necessary in reporting the mass data of social and economic trends, business conditions, opinion polls, the census. But without writers who use the words with honesty and understanding and readers who know what they mean, the result can only be semantic nonsense.

In popular writing on scientific matters the abused statistic is almost crowding out the picture of the white-jacketed hero laboring overtime without time-and-a-half in an ill-lit laboratory. Like the little dash of powder, little pot of paint, statistics are making many an important fact look like what she aint. A well-wrapped statistic is better than Hitlers big lie it misleads, yet it cannot be pinned on you.

This book is a sort of primer in ways to use statistics to deceive. It may seem altogether too much like a manual for swindlers. Perhaps I can justify it in the manner of the retired burglar whose published reminiscences amounted to a graduate course in how to pick a lock and muffle a footfall: The crooks already know these tricks; honest men must learn them in self-defense.

CHAPTER 1

The Sample with the Built-in Bias

T HE AVERAGE Yaleman, Class of 24, Time magazine noted once, commenting on something in the New York Sun , makes $25,111 a year.

Well, good for him!

But wait a minute. What does this impressive figure mean? Is it, as it appears to be, evidence that if you send your boy to Yale you wont have to work in your old age and neither will he?

Two things about the figure stand out at first suspicious glance. It is surprisingly precise. It is quite improbably salubrious.

There is small likelihood that the average income of any far-flung group is ever going to be known down to the dollar. It is not particularly probable that you know your own income for last year so precisely as that unless it was all derived from salary. And $25,000 incomes are not often all salary; people in that bracket are likely to have well-scattered investments.