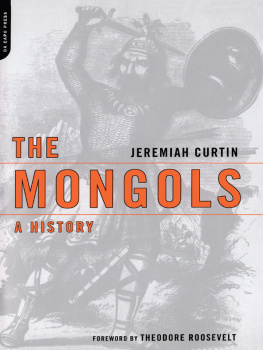

Jeremiah Curtin - The Mongols in Russia

Here you can read online Jeremiah Curtin - The Mongols in Russia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Perennial Press, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Mongols in Russia

- Author:

- Publisher:Perennial Press

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Mongols in Russia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Mongols in Russia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Mongols in Russia — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Mongols in Russia" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

IN MY HISTORY OF THE Mongols we have seen how Hulagu beguiled the Assassins and slaughtered them. We have seen also how he ended the Kalifat at Bagdad, showing no more regard for the heir of Mohammed than for the chief of those murderers who held that marvelous mountain-land south of the Caspian. The Kalif of Islam was trampled to death under horse-hoofs. The chief of the Assassins was treated with insult, endured for a time, and then slain like a wild beast.

We are now to consider an expedition planned at that Kurultai held during Ogotais election, and see what was done by its leader, an expedition which ruined large portions of Europe as far as the Adriatic, and made Batu, the nephew of Jinghis Khan, supreme lord of them.

The Mongols retreated from all lands west of the Carpathians and confined themselves exclusively to that part of Europe which we know as Russia. The West was too narrow for them, too mountainous, too much diversified, and contained too little pastoral land. It had too much culture, and differed too greatly from that immense open region which stretches from the Dnieper, or more correctly from the Danube, to that vast ocean of water which was later called the Pacific.

This region is made up of those spaces lying north of the Great Wall of China, that largest fence ever reared by man to ward off an enemy, and farther west by the greatest barrier raised upon earth through creation, and also used by man as a line of defense, a fortress of refuge, that unique mountain system extending from Eastern China to Persia, and then, with a break, to the Caspian. From the Caspian westward the immense space is bounded by the Caucasus and the Black Seat till it reaches the Danube and the mountains just north of that river.

This vast region, or Mongol careering ground as we may call it, began on the east at waters which are really the Pacific, and on the west touched the Danube, which finds its source very near the Rhone and the Rhine, both flowing into the Atlantic, since the North Sea, with its waters, is merely a part of that ocean.

The width of this region extends from the southern boundary just given to the Aretic, or Frozen Ocean. The entire southern part, somewhat less than Half of this entire area, was an open, treeless country, grass-growing land and sand plains. All along on the northern side of this southern division were great stretches of grass land, with small groves of trees, from one acre to one hundred in area. Lands of this kind are seen in Siberia to our day. In the center were fruitful spots, deserts and oases. In the east, next to the center, were boundless plains, with a greater proportion of forest toward the distant east and toward the north, but with clear spaces everywhere. On the south, from the Danube to the Chinese Sea, the country was open at all points.

Such was the Mongol careering ground, and after they had overrun Europe to the Adriatic and north of it they retired to the western part of this great open country of Eastern Europe, and made their capital at Sarai, just east of the Volga, and perhaps two hundred miles north of the Caspian.

But before writing of the Mongol invasion of Russia, it will be necessary to give a somewhat detailed history of Russia previous to that event.

It is, of course, not known when the Russians settled in their present territory. In the first half of the ninth century they occupied a large extent of land stretching from the Carpathians to the upper waters of the Don and the Volga, and from the neighborhood of Lake Ladoga to a point about half-way between Kief and the Black Sea. All this population lived in villages which were governed in patriarchal fashion by the heads of families. A number of village communities formed a volost, or district, which was the largest government unit in the country. The size of these volosts varied, according to the convenience or the necessities of the case, but in general they were small. As the Slavs were much attached to their village autonomy, and as there was an inexhaustible supply of land, it was quite impossible for a large community to subdue and absorb a weaker one, for the latter had always the power of removing to some unoccupied district and setting up its little republic in the wilderness.

The family system in force among the Slavs greatly favored this process, for a family was not, as in modern times, composed of parents and children only, but of two, three and even four generations. The head of this family was the oldest person in it, and its size was regulated by power of agreement among the members. There were often forty, fifty, or a hundred persons living in one family, all obeying a single head. A few such families formed a village, a few villages a volost, which was sometimes as large as one of our counties. The tendency of a society like this was altogether toward expansion. After reaching a certain size the village community divided, one part remaining in the old place, the other selecting a new field for its industry. It was only at a few points favorable for trade that a large number of people lived together Novgorod near Lake Ilmen was the most conspicuous example of this kind. It is evident that people living in this manner had little power of combination and could offer but slight resistance to invasion.

Novgorod, situated near the confluence of the different rivers, and in direct communication with the Baltic, became a great trading point, and was not only the most populous place in the whole country, but the first in which civil government began. It was a market-place for the goods of Europe and Asia, and soon rose to a position of wealth and importance. Its government was an extension of the communal system of the country, and was in fact a confederation of villages, held together very loosely. Such a place offered an excellent point of attack to the Northmen, the most enterprising and rapacious of mankind, who at that period left no European country in peace.

In the south the Kazars, a powerful Asiatic horde, took tribute and left the inhabitants to their own devices. This tribute was simply the price of being let alone. In the north it was different; the Scandinavians, who made their presence felt wherever they went, wanted not only profit, but power. They were greedy of rule, and wished to direct the affairs of Novgorod. This was unendurable; the citizens rose up, drove out the strangers, and began to govern themselves as in the old time. Theirs was no easy task, for the place was divided into parties, or rather factions, neither one of which had the power to govern. While affairs were in this troubled state, Gostomyal, the elder or president of the city, rose on a certain occasion and addressed the assembled multitude. Reminding them of their previous condition and present peril, he said that being easily inflamed by passion they were unfit to rule, that if they continued as they were the stranger would surely come, bringing dishonor to their wives and daughters and slavery to themselves, that too late they would shed bitter tears. He closed by advising them to invite from abroad some wise, strong man to govern according to their laws.

Under the immediate influence of this speech, a deputation was chosen and sent to the chieftain Rurik. The gist of their message was: Our lands are broad and rich, but there is no order therein; do thou come and rule over us.

Rurik came that same year, bringing with him his two brothers, Sineus and Truvor, and a certain force of his own, which was considerably increased after his arrival by native recruits. Who Rurik was is still a question among Russian historians, but it is generally conceded that he was a Scandinavian, though efforts have been made to show that he was from some Slav tribe on the southern coast of the Baltic.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Mongols in Russia»

Look at similar books to The Mongols in Russia. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Mongols in Russia and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.