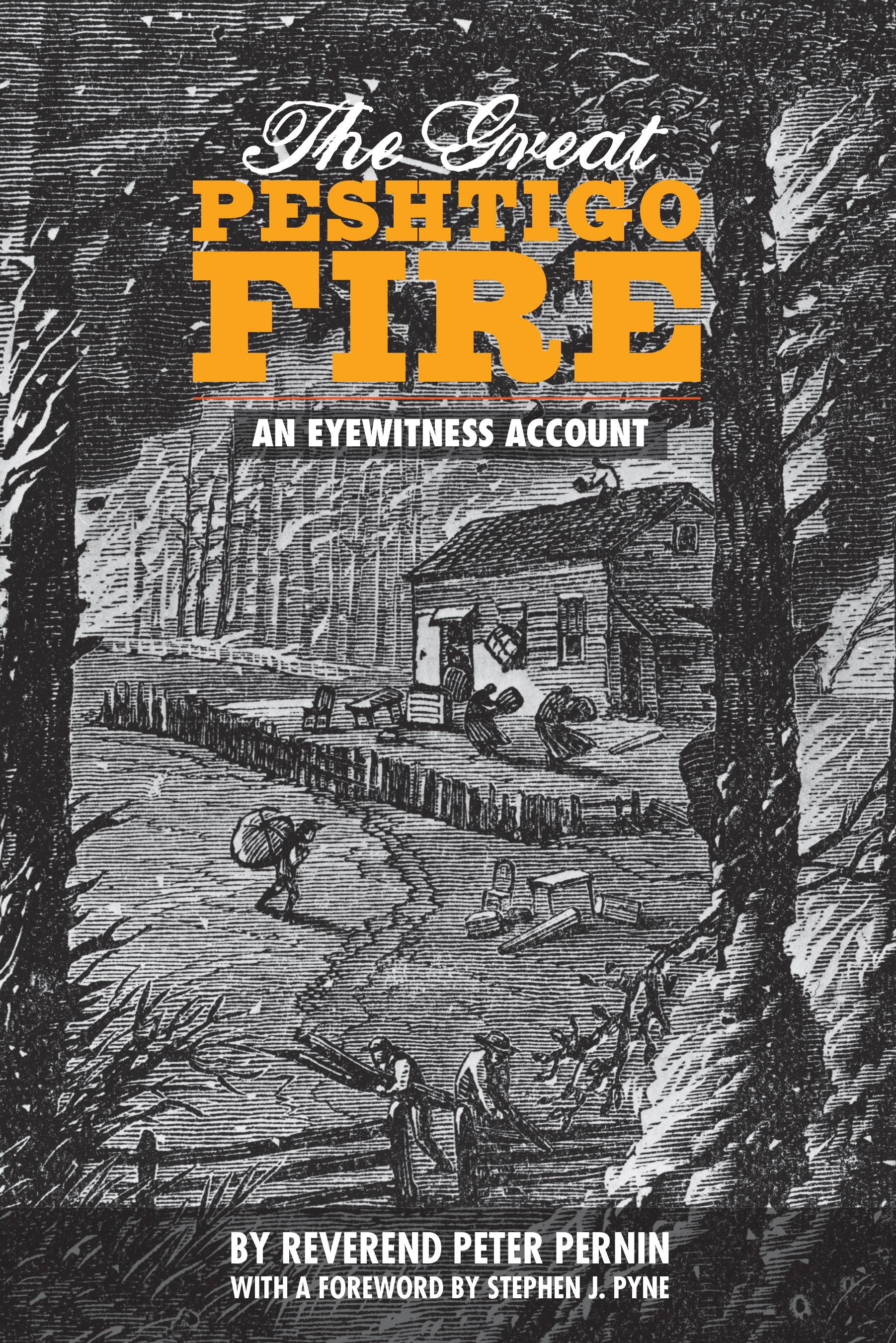

The Great Peshtigo Fire

An Eyewitness Account

By Reverend Peter Pernin

Second Edition

With a Foreword by Stephen J. Pyne

Introduction and Epilogue by

William Converse Haygood

Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Madison

1999

Copyright 1999

THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF WISCONSIN

All rights reserved. Permission to quote from or reproduce any portion of this copyrighted work may be sought from the publisher at

816 State Street, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706-1488.

ISBN 0-87020-310-X

The editors gratefully acknowledge the many people who made this edition possible. Special thanks to the local historians in Peshtigo who provided helpful information, including former Mayor Dale Berman. Cover design by Nancy Zucker.

On the cover: Illustration titled, Wisconsin House enveloped in flames . With special thanks to the Forest History Society, Durham, NC, for use of this image.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pernin, Peter, 19th cent.

The great Peshtigo fire: an eyewitness account /by Peter Pernin; with a foreword by Stephen J. Pyne and an introduction by William C. Haygood. --2nd ed.

ISBN 0-87020-310-X (paper)

1. Peshtigo Region (Wis.)--History--19th century. 2. Forest fires--Wisconsin--Peshtigo Region--History--19th century. I. State Historical Society of Wisconsin. II. Title.

F589.P48P471999

977.533--dc2199-27393

CIP

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

Maps

FORWARD

FORWARD

The Peshtigo Paradigm

By Stephen J. Pyne

Americas forgotten fire is anything but. It burned deeply into regional memory, its roster of dead qualifies it as one of the greatest quasi-natural disasters in North America, it springs from the pages of every survey of American fires, and its cachet as forgotten has paradoxically helped make it better known than almost any other rural conflagration, even the much larger Miramichi (northeast New Brunswick, 1825) and North Carolina (1898) fires. The holocaust that history knows as the Peshtigo Fire has never long passed from our national consciousness. In truth, the fire is one of a handful recognized generally throughout the world.

But these are far from the only reasons to recall it now. The firestorms meaningcall it the Peshtigo paradigmendures. The conflagration of October 8, 1871, illustrated a formula for forest fire disaster that has proved timeless. Its ravages contributed to a philosophy of conservation that has informed fire programs over the last century. And its descendant avatars flare today in Amazonia and Borneo, in California and Florida, and in the image of fire as the specter of ecological apocalypse. The fires of 1871 are not merely a historic relic: their story continues to be retold and deserves to be remembered.

What we call the Peshtigo Fire is a code name for a vast landscape of burning. The event raged within a regional complex that splashed across some 2,400 square miles and engulfed even Chicago. A prolonged drought, a rural agriculture based on burning, railroads that cast sparks to all sides, a landscape stuffed with slash and debris from logging, a city built largely of forest materials, the catalytic passage of a dry cold frontall ensured that fires would break out, that some would become monumental, that flames would swallow wooden villages and metropolitan blocks with equal aplomb. Far from diminishing the horrors of Peshtigo, the Chicago conflagration ensured that what happened in frontier Wisconsin would be recorded. Here was fires contribution to what environmental historian William Cronon has called Natures MetropolisChicago. Here was the grisly reality to match the metaphor coined for the post-Civil War era by Vernon Louis Parringtonthe Great Barbecue.

That domain of fire extended through time as well. When railroads punched into the North Woods after the Civil War, they set off a shock wave whose fiery aftertremors continued until the 1930s, when a combination of ecological exhaustion, economic conversion, and state intervention finally throttled routine wildfire from the land. These circumstances were not unique to the United States. Similar fires erupted along all of Europes colonial frontiers. They incinerated logging communities in northern Sweden; they pounced on Russian villages along the flanks of the Trans-Siberian railway; they gutted New Zealands North Island in 1885; they burned Gippsland, Australia, during the 1898 Red Tuesday fires; they blasted wooden towns in turn-of-the-century British Columbia and 1910s Ontario. Large fires were as characteristic of brash, relentless frontiers as wooden shacks and mud roads.

What happened in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, on October 8, 1871, was part of a ring of fire that continues to ripple around the globe. Analogous flames occur today. Substitute Xilinji and Ma Lin in Manchuria for Hinckley and Cloquet in Minnesota, and you have the Great Black Dragon fire that gutted three million acres in 1987 in Manchuria, devoured several rail-and-logging communities, killed hundreds, and left 33,706 homeless. The dynamics of wholesale land conversion in Amazonia, Borneo, and Sumatra that have so appalled contemporary environmentalists and have smothered Southeast Asia in smoke are exactly those that burned out the North Woods and forced lighthouses into action in midday along the shores of the Great Lakes. America was then a developing nation; it displayed the fire practices characteristic of one. If you want to understand why such immense areas are burning todaywhy they seem so intractableyou need only reconsider the Peshtigo paradigm and recall how stubbornly that fatal formula persisted in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota, well beyond the time when the United States considered itself an urban nation and a leading industrial power.

Again like modern fires, those of the late nineteenth century attracted critics and sparked calls for reform. Charred bodies, seared towns, and organic soils burned to sand were not inducements for further settlement, the investment capital of future wealth, or the signatures of a civilized people. Such fires argued for an emerging philosophy of conservation in ways that the subtle tracking of soil erosion or protests over killing of flamingos could not. The lethal burns shouted the inadequacy of laissez-faire settlement by ordinary folk. Gilded Age America was the burning Brazil of its day. Years later, when Aldo Leopold elaborated his ideas on land ethics and stewardship, he included the 1871 fires as an environmental milepost. His Sand County Almanac (1949) derived from a site logged, burned, and abandoneda synecdoche for the regional havoc that Peshtigo so aptly symbolized.

The actual reforms emerged elsewhere. The creation of public lands, particularly national forests, was intended to prevent the wholesale wastage that had so pillaged the North Woods. The immediate prods for federal fire protection, especially, were the 1903 and 1908 fires in the Northeast and the 1902 and 1910 fires in the Northwest. But behind them stood the memory of Peshtigo. The creation of a forestry establishment, in turn, helped dampen the fury of the rural fire scene. Peshtigo rose from the ashes. Eventually, tree farms replaced stump farms, the woods were reseeded, tourists succeeded transient loggers, fields regrew as summer home sites. And the fires returned.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

FORWARD

FORWARD