INTRODUCTION

GLEAMING

EVERYWHERE

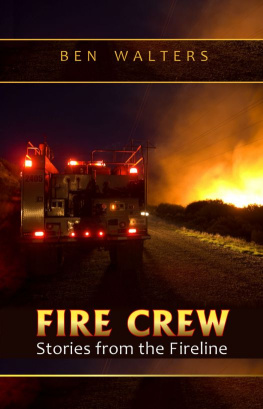

Mike was first to spot the smoke.

There, he said, and swung the nose of the helicopter a few degrees southeast.

A lazy white plume curled out of a pine stand near the crest of a ridge. Fanned by treetop wind, it quickly dispersed to haze. I keyed the radio.

Flathead Dispatch, this is helicopter Alpha-Hotel-Romeo. We have the smoke in sight. Stand by for a size-up.

We were close to Blacktail Mountain, in the Salish range, a dozen miles south of Kalispell, Montana. The crystalline expanse of Flathead Lake was two ridgelines to the east. It was August 26, 2000, and wildfires had been rampaging throughout the northern Rockies since mid-July.

In a minute we were over the newest one, Mike banking steeply to the left so I could gaze straight down into the trees. The fire was still small, partially hidden by the forest canopy and shielded from wind. A timely attack would catch it. Since it was near the top of the slope, there wasnt much room for it to run. Ground forces were rolling from Boorman Station at Little Bitterroot Lake but were nearly an hour away.

I had three crew members in the backseats, and over the intercom I offered a benediction: This one is ours.

Doug responded with a terse, emphatic, Yes!

As Mike swung the Bell 212 north to search for a landing zoneor helispotI radioed a brief report to Flathead Dispatch, then pointed to a clearing about 200 yards below the fire.

What about that, Mike?

Hed seen it but wasnt impressed. The wind was unfavorable for an easy landingthe air on the lee side of the ridge might be squirrelly, with troublesome eddies on the downslope. And the ground looked rough. As Mike eased us in for a better look, we saw it really wasnt ground at all but a thick mat of old logging slash. Still, it was ideal in reference to the fireunusually close and safely below.

Okay. Lets give it a try, he said, deadpan, as usual. To call Mike taciturn was an understatement. In nearly two months of fire and flying, Id yet to witness him agitated. He was forty-five years old and had 13,000 hours at the controls of a helicopter. He was cool to the point of cadaverous.

He brought Alpha-Hotel-Romeo in slowly, and I cracked open my door to gain a clear view of the left skid. The crew did the same in back, leaning out to scan for the best spot in the tangle of limbs and logs.

Looks good on this side, I said.

But in the rear Doug saw a protruding stump. A foot to the right!

Mike jiggled the cyclic stick a fraction of an inch.

Okay.

I could see he was struggling a little.

The ship settled and for a moment felt spongy. Mike lifted us a foot, crabbed left, and settled again. We were tilted slightly to the right, but it felt firm enough.

Just before I unplugged my avionics, Mike turned and said, deadpan of course, That was fun. I wont be picking you up here.

I grinned. Ten-four.

The thing was, we were here, now. At a fire. Wed worry about the pickup later.

I doffed my flight helmet, stowed it between the seats, and grabbed my fireground hard hat on the way out the door. Doug and the crew were muscling the 150-pound, 320-gallon Bambi Bucket from a cargo compartment, and I positioned myself forty feet in front of the ship so I could monitor the operation, acting as safety officer and, I thought, as a kind of priest.

Since June 1 wed practiced this bucket deployment in dry runs and wet runs, refining the sequence to the point of ritual. I once musedonly half in jestthat crew members were like altar boys or vestal virgins, precisely performing a sacred rite. We honed it to fine detail, knowing which hand would be used by what person to manipulate a given buckle, latch, or handle. The task was to hook the bucket to the belly of the ship and test it, then transform ourselves from air crew to fire crew. The goal was rapid perfection, speed without stumbling.

One of our training manuals asserts that fireground air operations, like maritime activities, are not inherently dangerous, its just that they unfold in a tenaciously unforgiving environment, intolerant of mistakes. One miscue can court disaster. I count this drill a ritual because it can kill you. I know of a colleague who, during such a procedure, made a mistake. A few seconds later, a helicopter was trashed, a pilot injured, and the colleague decapitated by a tail rotor. That was a sacrifice we wished to avoid.

One of the relief pilots called our crew a well-oiled machine. I preferred to think of us as ceremonial dancers, preparing for the next baptism of fire with careful choreography. Because the stakes are high and final. All summer wed been stationed in northeastern Minnesota, prepared for initial attack in the Blowdown25 million broken, uprooted trees, the biggest fuel load in North America. A July 4, 1999, megastorm had flattened 477,000 acres of the Superior National Forest, mostly in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, and in 2000 there was acute potential for magnificent, dangerous fires in remote and rugged terrain. We trained and drilled with that in mi n d. Sooner or later the Blowdown would burnbig-time. Meanwhile, there was Montana.

When the bucket was ready, our flight gear stowed, and our hand tools and fireline packs secured on the ground, the crew gathered behind me. I scanned earth and sky, searching for any defectsanother aircraft, a control head cable draped over a skid, a loose item in the rotorwash. Satisfied the scene was righteous, I gave Mike a jubilant thumbs-up. Alpha-Hotel-Romeo powered away for a nearby lake. Pulling my earplugs, I briefly surveyed the bright, open faces of the crew.

Shall we go? I asked.

A chorus of boyish hoots.

We donned our packs, picked up our pulaskis (a combination ax and grub hoe) and chain saw, and headed upslope for the fire, a happy band of brothers eagerly hiking toward the drudgery and perils of the fireground.

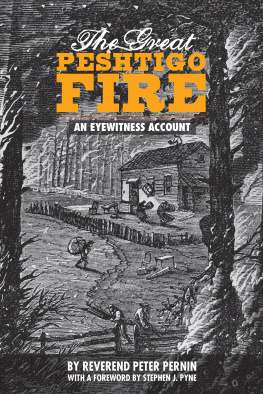

But this joyful anticipation of struggle is not the only face of fire. A happy band is not the only congregation to frequent smoky woods. The minions of terror and death are also illuminated by torching trees. And never with such an awful brightness than was seen in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, on an October day 130 years ago.

On September 22, 1871, the Reverend Peter Pernin, age forty-six, a Catholic priest in northeastern Wisconsin, was on a routine ministerial mission at the Sugar Bush, a collection of farms near the town of Peshtigo. The twelve-year-old son of a local parishioner offered to guide him on a pheasant hunt, and they ventured into surrounding woods. The Reverend recorded no kills, and a few hours later, near sundown, he suggested the boy lead him back to the homestead. Soon it was apparent they were lost. Darkness was settling, and the autumn forest was quiet except for the crackling of a tiny tongue of fire that ran along the ground, in and out, among the trunks of the trees, leaving them unscathed but devouring the dry leaves.

The summer of 1871 had been uncommonly arid, with only two rainfalls from July through September. Local farmers seized the opportunity to expand their fields, felling dense forest and burning the residue of limbs, foliage, and stumps. This was standard practice, slash-and-burn agriculturewhat we now consider Third World land mis-management. As historian Stephen Pyne has written, Gilded Age America was the burning Brazil of its day. In 1831, Gustave Beaumont, a companion of Alexis de Tocqueville, observed the pioneers of the young nation hacking farms out of forest. He noted there was in America a general hatred of trees. The autumn fires of northeast Wisconsin were no remarkable event, and Father Pernin wrote, In this way the woods, particularly in the fall, are gleaming everywhere with fires lighted by man.