Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

wisconsinhistory.org

2010 by State Historical Society of Wisconsin

For permission to reuse material from Monster Fire at Minong (978-0-87020-447-0), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

Photographs identified with WHi or WHS are from the Society's collections; address requests to reproduce these photos to the Visual Materials Archivist at the Wisconsin Historical Society, 816 State Street, Madison, WI 53706.

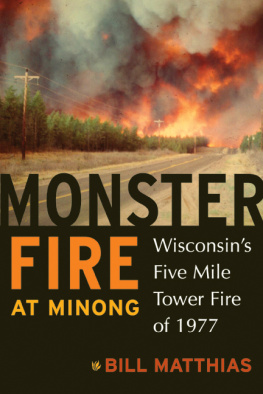

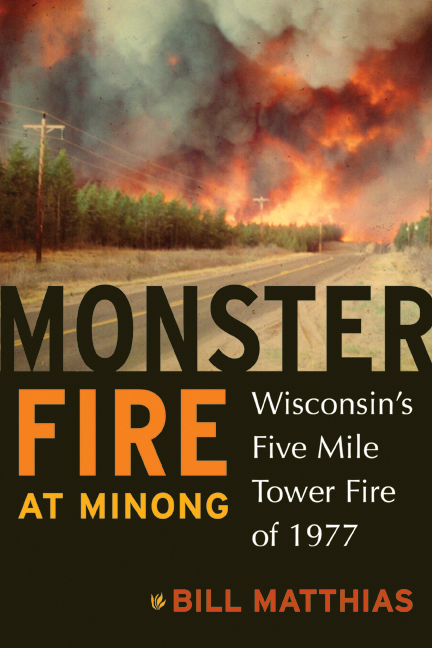

Front cover photo: Wisconsin DNR file photo by Bill Hoyt

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Andrew Brozyna, AJB Design

Interior design by Jim Primock

14 13 12 11 10 1 2 3 4 5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Matthias, Bill.

Monster fire at Minong: Wisconsin's Five Mile Tower Fire of 1977 / Bill Matthias. 1st ed.

p.cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-0-87020-447-0 (alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-87020-447-0 (electronic)

1. Five Mile Tower Fire, Wisconsin, 1977. 2. Washburn County (Wis.)History 20th century. 3. Douglas County (Wis.)History20th century. 4. WildfiresWisconsinPrevention and control. I. Title.

SD421.32.W6M48 2010

363.370977515--dc22

2009023093

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

Dedicated to my parents, Vilas Matt" Matthias (1914-2004), professor emeritus, University of Wisconsin College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, and Gladys (Wehrwein) Matthias.

Since they purchased property in the sandy soils of northwest Wisconsin in the mid-1950s, I have grown to love the pines, scrub oaks, and deep, cold, clear lakes of the region.

Publication of this book was made possible in part by donations from

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

Wascott Volunteer Fire Department, in memory of Jamie Forbes

John Deere Construction & Forestry Co.

Gladys Matthias

John R. Liautaud

Ellen F. Buck

GR Manufacturing, Inc.

Biewer Wisconsin Sawmill, Inc.

Pierce Family Fund of the Minneapolis Foundation

L. Peter Patrick

Mary Beth Smith

Chester J. Hoversten and Clenora Hoversten

Richard A. Nelson

During research for Monster Fire at Minong, the author interviewed more than 135 people about their experiences on the Five Mile Tower Fire and its aftermath. He also incorporated his own recollections about the fire. Every attempt has been made to capture an accuate description of the events, participants, and experiences, and any inaccuracies or omissions are unintentional. If you are aware of any errors in this text, please send your comments to billmatthias@hotmail.com.

There are thousands of stories about this fire, and limited time and space to record them in this book. The author would like to hear from you if you had an experience in this fire that you would like to share for possible inclusion in a future edition of the book.

Introduction

I bend down to tee up the ball. On a warm day in 2006, my wife, Karen, and I are enjoying nine holes of golf at Fire Hill Golf Club in Gordon, Wisconsin. Chunky clouds race across the sky, pushed by spring's southwest-prevailing winds. Most people who play here dont know how the course got its name, but as my typical amateur opening drive slices into the jack pine grove, I know. I look across the expanse of green fairway to the forest in the distance and see the trees there, all the same size. I shiver as memories flood back.

Nearly thirty years earlier I was in this area under much different circumstances. The winds were blowing then, too, hot and full of smoke and soot. The trees were twice as tall, and our world was burning. Near 3:00 a.m. I was driving my pickup truck behind a group of Gordon fire trucks on Hill Road. As we turned into the driveway of the Russell Hill estate, the jack pines burned on both sides of the narrow path. We had to close our windows so our arms wouldnt burn. Suddenly we came to a clearing, where the main house stood ready to burst into flames. Two garages, a painting studio, and a barn were already on fire. The grass, pine needles, and trees in the compound were bright with flames. I jumped out of the truck to help haul fire hose. Only a few feet away, a fifty-foot-tall red pine exploded. Several of us scrambled away from the tornado of sparks and flying embers. The noise was so loud we had to shout to be heard. I looked up and saw that stately tree turn into a swirling, flaming beast, shooting a spiral of fire one hundred feet into the sky. The falling chunks of burning bark and twigs immediately set off hundreds of other fires in the dry leaves, needles, and brush. We ran from the deadly shower. Our small group had saved the Hill home, but all of the other buildings were reduced to flaming skeletons as we watched the roofs cave in.

That was in 1977. Along with hundreds of others, I had been fighting a monster fire for twelve hours, and it still wasnt out. I was dirty, smelly, tired, hungry, and thirsty. Wherever I looked across the fire scene, spread over twenty-two square miles, I saw death of animals, destruction of forestlands, flames here, blackness there. Trucks, men, women, equipment, dozers, and plows. People hunched over from the weight of heavy, water-filled backpack can sprayers. Men and women with shovels following plowed trails to put out lingering flames.

Two years earlier, I had been selected by the five-member North-wood School District Board of Education to be its district superintendent. Northwood was a small district; I was the administrator for two principals, forty teachers, and five hundred students in two schools with ten bus routes. Our district was spread over 430 square miles of forestlands, a few farms, and many beautiful lakes. Student density was just over one student per square mile. Everyone living in the region was attuned to rural life, enduring such realities as long travel distances, few close neighbors, severe cold in the winter, and swarms of mosquitoes, wood ticks, and biting deerflies come summer. But such remote living offered many benefits. There was hunting in beautiful wooded settings, fishing in clear, cold lakes, and the enjoyment of regularly seeing deer, bear, coyotes, foxes, eagles, and osprey. And as far as the eye could see, there were trees.

I also was a private pilot and often rented Piper airplanes at Bong Field in Superior and flew south to look over our region. I would marvel at the trees carpeting northwest Wisconsin from horizon to horizonso dense it was hard to spot major roadways from the sky.

In the mid-1950s, my parents had purchased red pine plantations and oak forestlands in Wascott, between Pickerel and Bond Lakes. I had grown to love these lands and lakes, and when Karen, our young son, Mark, and I returned from a year in Tripoli, Libya, where I was the principal of the Oil Companies School, we dreamed of the possibility of living and working in the Wascott area. When I was hired as superintendent, we moved into an A-frame cabin we had built on Bond Lake six years earlier.

Having been a forestry student in my early days at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and now living so close to the landeating venison and fish, burning wood I cut and split myself, and wishing to help protect the precious resource of forestlandsI was acutely interested in firefighting and forest protection. I worked with the school board, staff, students, and Department of Natural Resources (DNR) rangers Bill Scott from Minong and Barry Stanek from Gordon to establish two student forest firefighting crews made up of mostly juniors and seniors at Northwood High School. The school board had approved the necessary policies, and parent permission slips were on file. Parents fears were allayed by the knowledge that the youths were trained properly and covered by state insurance policies, including workers compensation.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.