Table of Contents

RIVER OF FIRE

THE RATTLESNAKE FIRE AND THE MISSION BOYS

JOHN N. MACLEAN

COPYRIGHT 2018

::: ALL RIGHTS RESERVED :::

RIVER OF FIRE

The Rattlesnake Fire and the Mission Boys

COPYRIGHT 2018 John N. Maclean

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

An earlier version of this story was included in the book

Fire and Ashes , published in 2003 by Henry Holt and Co.

Cover and interior photos by Kari Greer kariphotos.com

Editing/design by AnderssonPublishing.com

Maps by John N. Maclean, Kari Greer and Kelly Andersson

NO PART OF THIS BOOK, WITH THE EXCEPTION OF BRIEF QUOTES OR EXCERPTS FOR REVIEW PURPOSES, MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR ANY MANNER, ELECTRONIC OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE AND RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE AUTHOR.

Some discounts may be available on quantity purchases by fire crews, associations, and others.

Contact the author at JohnMacleanBooks.com

ISBN: 978-0-692-07998-0

ALSO BY JOHN N. MACLEAN

FIRE ON THE MOUNTAIN

The True Story of the South Canyon Fire

FIRE AND ASHES

On the Front Lines of American Wildfire

THE THIRTYMILE FIRE

A Chronicle of Bravery and Betrayal

THE ESPERANZA FIRE

Arson, Murder, and the Agony of Engine 57

DEDICATION

To Kelly Andersson, my longtime backstop

INTRODUCTION

It was evening, about 10 p.m., when the wind over a brush-choked canyon in northern Californias Glenn County unexpectedly shifted and began to roar downhill.

A fire had been burning since midday on the upper reaches of the canyon on the Mendocino National Forest, a bit over 100 miles north of Sacramento. The fresh, violent wind picked up embers from the fire and spun them down into the depths of the canyon, where the embers transformed into a thunderous torrent of fire, as though a dam had burst.

The sight mesmerized veteran firefighters. Long, fatal minutes passed before they remembered a crew of twenty-four men stationed in the canyon below. The crew had hunkered down in a ravine to eat supper and had posted no lookouts.

The alarm was raised, but it was late. Fifteen of the men in the lower crew began a race with fire down the canyon while another nine scrambled upward to safety. Other firefighters watched in horror from canyon slopes as the torrent of fire hurtled toward the fifteen men and snuffed their headlamps, one after another.

The loss of fifteen firefighters on the Rattlesnake Fire, which occurred July 9, 1953, stood unmatched for many years, but it sparked a nationwide program to deliberately burn chaparral and reduce the risk of uncontrolled fire. The program, though, was severely curtailed under a series of environmental challenges beginning in the 1970s.

The Rattlesnake Fire helped inspire rules for wildfire safety that remain in force today. The Forest Service, conscience-struck by a mounting death toll from this and other fires, assembled a task force in 1957 that produced the Ten Standard Fire Orders, the bedrock of firefighter safety, and the number of multiple-fatality fires dropped dramatically after 1957.

The fire also provided a lesson about the limits of punishment for arson. Stan Pattan, the son of a prominent Forest Service engineer, confessed to setting the Rattlesnake Fire so he could get a job on the fire crew. He was taken into custody while working as a cook at the fire camp. Pattan served three years of a possible twenty-year sentence in San Quentin but he dodged murder charges and a more severe sentence because he had not intended to harm anyone. He returned home, where he worked many years as a wildlife artist and had no further trouble with the law.

The spring after the Rattlesnake Fire, two young Forest Service men, dismayed by the loss of life, took drip torches and on their own authority ignited a huge swath of chaparral near the site of the fire. Deliberate burning, they believed, would have prevented the deaths on the Rattlesnake Fire.

The Forest Service, to its credit, didn't discipline them but instead made the burn a model for the region.

Hopefully, there is some solace in the fact that this tragedy woke up the Forest Service and other firefighting agencies, Dan Chisholm, supervisor of the Mendocino National Forest, said at a 1993 memorial dedication near the fire site.

But fire remains a brutal teacher. The ongoing losses of firefighters underscore the truth that fire ultimately eludes human control. The effects of fatal fires linger like heavy smoke for those who knew and loved those who fell. Hope lies in sifting the ashes to learn a lesson, no matter how imperfectly.

~ From an op-ed by John N. Maclean

published in the Los Angeles Times, October 2013

FOREWORD PASSING IT ON

Don Will, May 2018

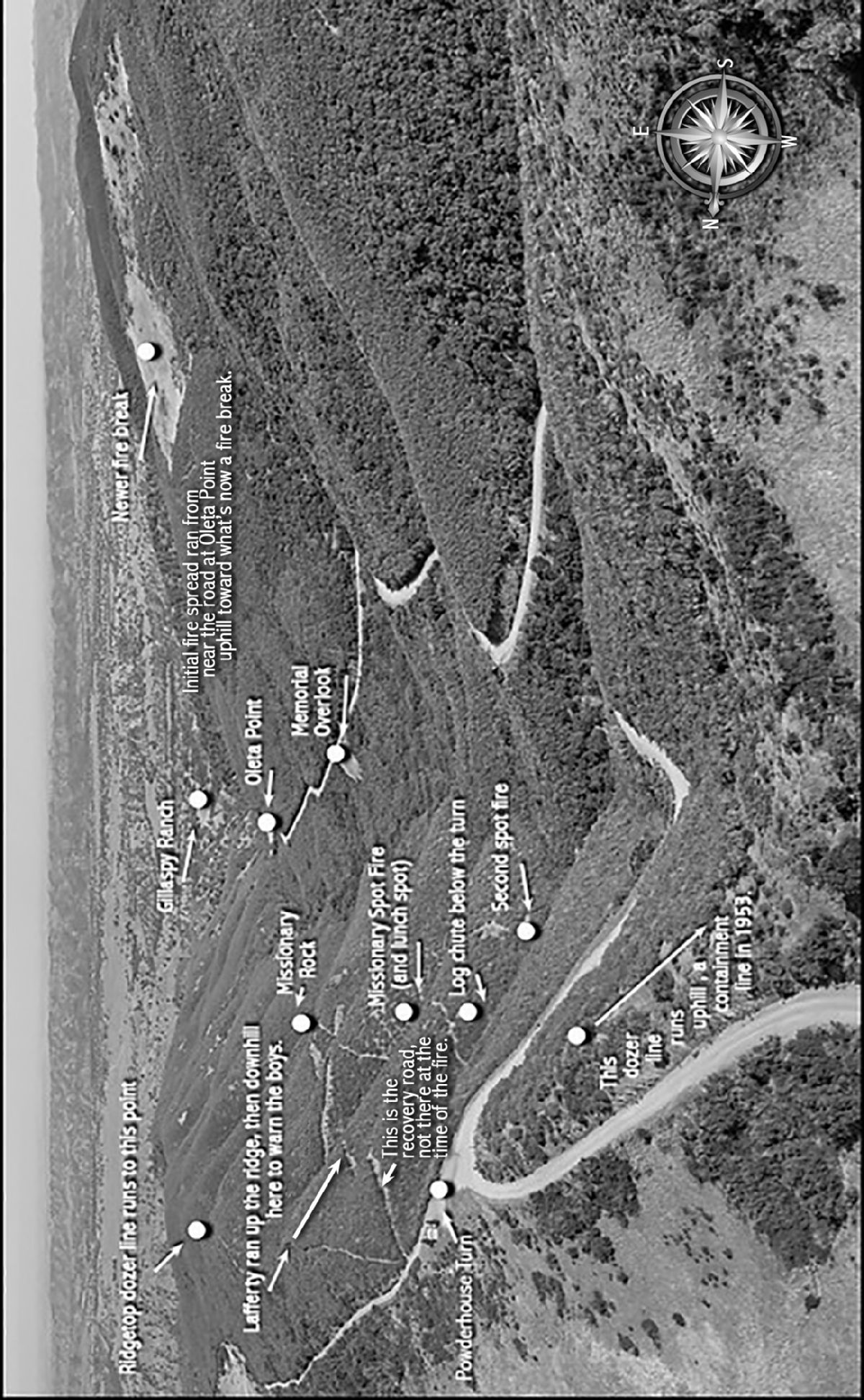

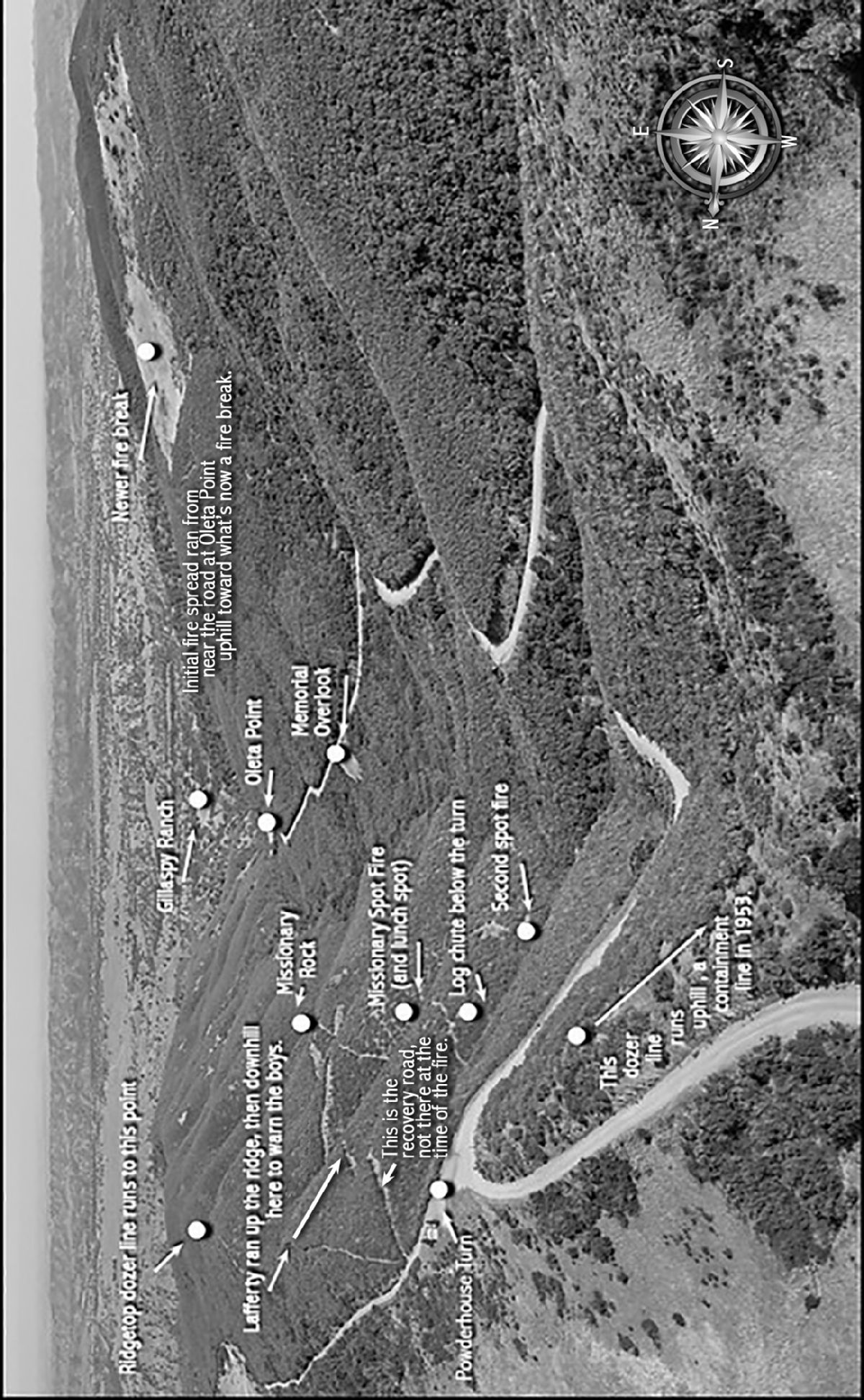

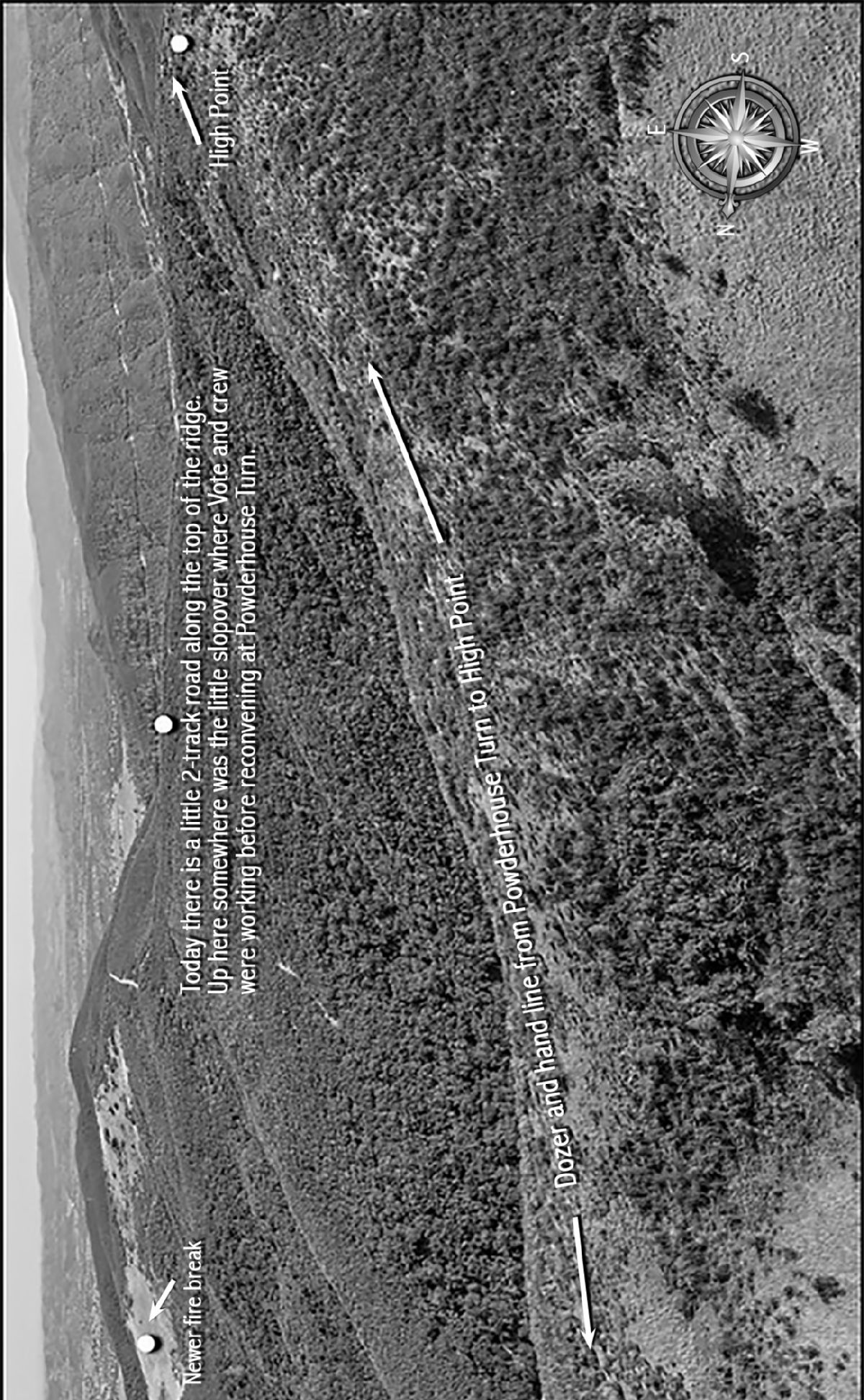

R ATTLESNAKE CANYON IS A SPECIAL PLACE to me. I find a strange sense of peace and tranquility every time I go there. Each spring I hook up my 23-foot travel trailer and head to Long Point and set up there for a couple of days. Its a nice flat ridge with a view off to the east, looking down on Powderhouse Turn.

I go there each year to reflect and remember. Remember young men who perished there. I consider it one of my duties, to remember and to be a conduit of the past, to keep their sacrifice alive.

View from the site of the old Long Point Lookout

While there I start each day with a slow drive down Forest Road 7, past the memorial the USFS put up on the new Highway 7, which leads one to look out over Grindstone Canyon. Its a misleading memorial, on the ridge that divides Rattlesnake Canyon and Grindstone Canyon. Its an error we corrected back in 1993 when the Mendocino Hotshots packed a big wooden cross into Rattlesnake under the cover of night and set it at the site where the Missionary boys perished.

I always park at Powderhouse Turn, and there I take a few moments to breathe the air, feel the wind, smell the spring chaparral.

I think of Charlie Lafferty, who was a family friend of my uncle, Gil Ward. He worked with Charlie and they were lifelong friends. Uncle Gil told me that he and Charlie used to drive up Forest Road 7 and burn out the turnouts in the spring, so that hunters stopping to smoke there wouldnt start a fire. I think often of Charlie and the remorse he carried for the rest of his days.

I always walk down to the site of the spot fire and sit. Its very pleasant there on a spring morning. Birds are flittering around, wildflowers are blooming, and the chaparral has a green-up fragrance. I sit right where the Missionaries sat and had their lunch that fateful night in 1953. I imagine I can hear their voices, hear their crew banter, hear their pre-meal prayer.

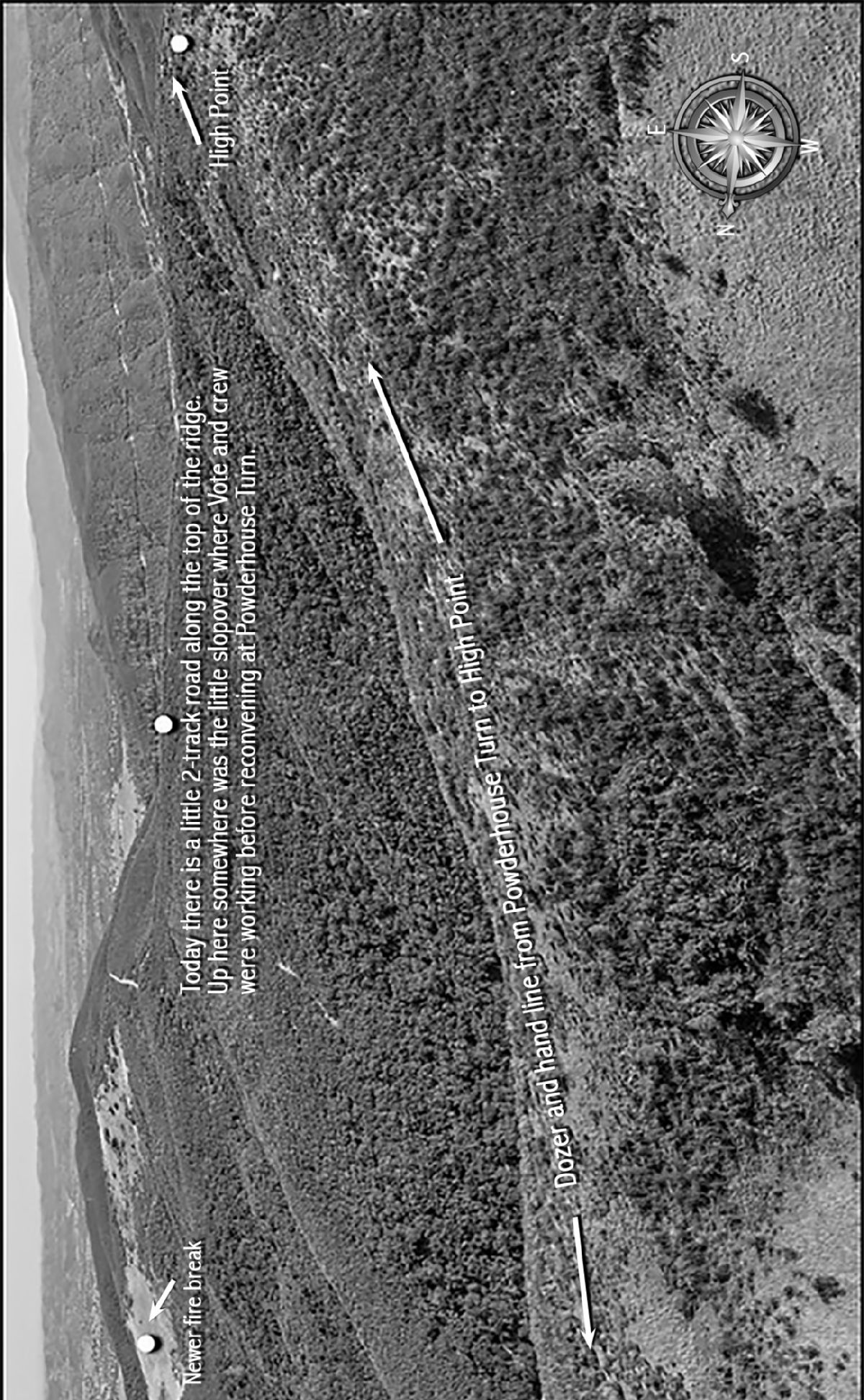

I continue on then, up the escape trail they took when Charlie made his gallant run to warn them to run downhill, away from the fire. I reach the first cross, then the next. I think of what they were feeling as the fire was chasing and overtaking them. I think of those young men in the prime of life clawing their way through the thick chaparral at night. I reach the small ridge where Stanley Vote broke away and bulled his way straight uphill trying in vain to reach the top of Powderhouse ridge, and safety. I always climb to his cross and let him know we remember.

Next page