The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

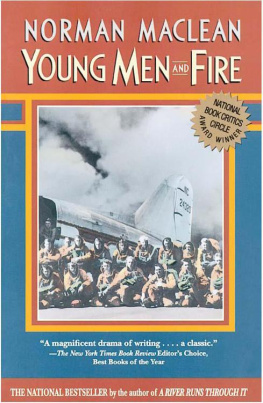

For my father and mother, Norman Fitzroy and Jessie Burns Maclean, in grateful memory

NORTHWEST REGULAR NO. 6 CREW LIST

NAME | POSITION | HOME DISTRICT |

Ellreese Daniels | Incident commander | Lake Leavenworth |

Pete Kampen | Crew boss trainee | Lake Leavenworth |

SQUAD ONE |

Tom Craven | Squad boss | Naches |

Beau Clark | Firefighter | Naches |

Jason Emhoff | Firefighter | Naches |

Karen FitzPatrick | Firefighter | Naches |

Scott Scherzinger | Firefighter | Naches |

Rebecca Welch | Firefighter | Naches |

SQUAD TWO |

Thom Taylor | Squad boss | Lake Leavenworth |

Armando Avila | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

Nick Dreis | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

Elaine Hurd | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

Jessica Johnson | Firefighter | Naches |

Matthew Rutman | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

Devin Weaver | Firefighter | Naches |

SQUAD THREE |

Brian Schexnayder | Squad boss | Lake Leavenworth |

Dewane Anderson | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

Emily Hinson | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

Jodie Tate | Firefighter | Naches |

Marshall Wallace | Firefighter | Naches |

Donica Watson | Firefighter | Lake Leavenworth |

CHAPTER ONE

You wont find any white collars here.

Dont come looking for easy cash.

We fight the fires in your lost canyons,

Faces stained by sweat and ash.

from Storm King Angels by Chip Kiger

As Kathie FitzPatrick struggled to bring a bickering home buyer and seller to terms, she stole a glance at her watch. It was almost 5:30 PM , and once again her workday had stretched into evening. Kathie had snatched a personal moment a few hours earlier to place a cell phone call to her eighteen-year-old daughter Karen, who had just become a wild-land firefighter for the Forest Service, much against her mothers wishes. Karen had left the night before for the first big fire of her career, in the North Cascades Range in central Washington, about two hundred miles north of the FitzPatrick home in the Yakima Valley. The phone had failed to make a connection, a regular occurrence since Karen had graduated from high school the previous month, in early June, and headed for the backcountry and out of cell phone range. Kathie would try again later in the evening, when Karen might be settled in a fire camp.

Kathie put in long hours as a real estate agent, was mother to three grown-up daughters, and in what time remained led a Christian ministry to juvenile delinquents, called the Young Lions Youth Ministry Program. The social fault line for the Yakima Valley, the heart of Washingtons bountiful fruit and hops industry, runs between orchard owners and their middle-class allies, and an underclass of low-paid migrant fruit pickers. The resulting high crime rate brought Kathie plenty of prospects to evangelize at the Yakima County juvenile detention facility.

Still, family was the first priority. Her youngest daughter, Karen Lee FitzPatrick, had been a tomboy until her midteens, a lanky, lantern-jawed girl with a handshake like a vise clamp. With the coming of adolescence, though, Karen had blossomed into a real dish, ladylike and elegant. What in the world had possessed the girl to become a firefighter? Kathie wondered. Firefighting was dirty, physically demanding, and dangerous, no occupation for a lady.

The callout for Karen and her Naches Ranger District fire crew, based near Yakima, had come just after midnight. They initially were assigned to the Libby South Fire, the first big blaze of the season in the North Cascades. Libby South had grown into a major rager, likely to destroy a lot of homes and other property if not stopped or turned. That effort would take many hundreds of firefighters, as well as aircraft, bulldozers, and other heavy equipment. Ironically, the fire had been started a day earlier, on Monday, July 9, 2001, by the hot exhaust of a state vehicle on fire patrol. Confined within a narrow canyon, the flames had made a series of wind-driven runs that first afternoon, lofting from the crown of one tree to another in what became a sweeping blanket of fire. Conditions had become so extreme that smoke jumpers, the airborne troops of firefighting and the first to fight the blaze, had pulled back from their lines in late afternoon. Thankfully, no one had been injured.

Weather conditions for the area for the next day, Tuesday, July 10, were a repeat of the first day: temperatures rose into the hundreds in hot spots, and the humidity dropped toward single digits nearly everywhere, on top of three straight years of drought. Gary Bennett, a fire meteorologist assigned to the Libby South Fire, awakened that morning with an ominous feeling that something could go seriously wrong. He had opened his morning briefing at fire camp by warning, Today will be a carbon copy of yesterday, by which he meant that firefighters should be alert for another wind-driven blowup.

Nobody missed the message. The dramatic fire runs the previous day had galvanized attention across the region. New blazes were sure to break out as well, and with the Libby South Fire grabbing attention and resources, the little fires could cause trouble if not dealt with quickly.

Indeed, a new smoke had been spotted the previous evening, Monday, July 9, not many miles to the north in the narrow Chewuch River canyon near the Canadian border. Named the Thirtymile Fire, the newcomer amounted to no more than a single thread of smoke when first observed. If it ever got going, though, it could burn out the canyon and rampage on into Canada. A local engine crew, dispatched within minutes, had driven into the canyon in the dark and found a handful of glowing spot fires spread over five or six acres along the Chewuch River, which is big enough to hold salmon.

The Thirtymile Fire should have been a mop-up operation, swiftly extinguished after being spotted early. But the fire was an elusive trickster, a grab bag of quirky moves and false signals that masked a lethal potential. Lone trees torched up or candled seemingly without an ignition source. Flames in the dense underbrush sent aloft streamers of embers, as though someone was shooting off fireworks left over from the Fourth of July. The glossy, fireproof look of the riverine vegetation was deceiving: the odd ember found a cozy nest in dry duff, incubated, and in time emerged as yet another darting flame or flaring tree.