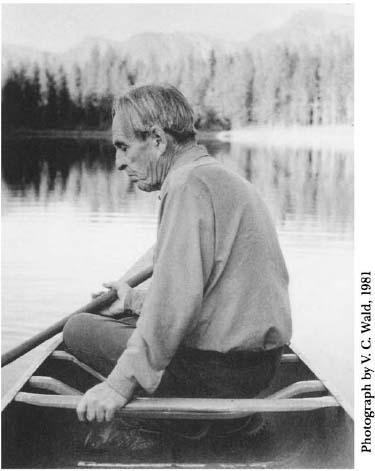

NORMAN MACLEAN was born in Clarinda, Iowa, in 1902 and grew up in Missoula, Montana. He worked for many years in logging camps and for the United States Forest Service before beginning his academic career. A scholar of Shakespeare and the Romantic poets, Maclean was William Rainey Harper Professor of English at the University of Chicago until his retirement in 1973. His acclaimed book A River Runs Through It and Other Stories was published by the University of Chicago Press in 1976. Norman Maclean died in 1990.

Young Men & Fire

NORMAN MACLEAN

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

1972 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 1992

Paperback edition 1993

Printed in the United States of America

08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 11 12 13 14 15 16

ISBN: (cloth) 0-226-50061-6

ISBN (paperback) 0-226-50062-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Maclean, Norman, 1902-90

Young men & fire / Norman Maclean.

p. cm.

1. Forest firesMontanaMann GulchPrevention and control 2. SmokejumpersUnited States. 3. United States. Forest ServiceOfficials and employees. I. Title. II. Title: Young men and fire.

SD421.32.M9M33 1992

634.96180978664dc20

92-11890

CIP

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

eISBN: 9780226500621

Contents

As I get considerably beyond the biblical

allotment of three score years and ten, I feel

with increasing intensity that I can

express my gratitude for still being around on

the oxygen-side of the earths crust only by

not standing pat on what I have hitherto

known and loved. While the oxygen lasts, there

are still new things to love, especially

if compassion is a form of love.

NORMAN MACLEAN

Notes written as a possible forepiece to

Young Men and Fire , December 4, 1985

Publishers Note

T HOUGH HE HAD HOPED for many years to write about the Mann Gulch fire, Norman Maclean did not start work on this book until his seventy-fourth year, after publication of A River Runs Through It and Other Stories. He began Young Men and Fire partly in the spirit of what he liked to call his anti-shuffleboard philosophy of old age, but partly, too, out of a deeper compulsion. In Macleans files after his death were found some notes toward a Preface, written in 1984. The problem of self-identity, Maclean wrote, is not just a problem for the young. It is a problem all the time. Perhaps the problem. It should haunt old age, and when it no longer does it should tell you that you are dead. Young Men and Fire was where, near the end, all the lives he had lived would merge: the lives of a woodsman, firefighter, scholar, teacher, and storyteller.

When Maclean died in 1990 at the age of eighty-seven, Young Men and Fire was unfinished. The book had resisted completion because the facts of the catastrophe proved so protean and because Macleans stamina began finally to wane. But more important, Young Men and Fire had become a story in search of itself as a story, following where Macleans compassion led it. As long as the manuscript sustained itself and its author in this process of discovery, it had to remain in some sense unfinished.

After Macleans death, it was left for the press to prepare Young Men and Fire for publication. Our editing has not altered the structure of the book, and we have kept substantive interpolations to a minimum. We have done the kind of stylistic editing that we believe Maclean himself would have done if he had had the time, and we have cut certain repetitions in the manuscript. Facts have been checked for consistency and accuracy and occasionally corrected, but they have not been updated beyond 1987, the year Maclean became too ill to work further on the manuscript. We have added the present chapter divisions, although the breaks within these chapters are Macleans, as is the division of the book into three parts. Black Ghost, the story that opens this book, was found in Macleans files after his death, his exact intentions for it unclear. We print it here as a fitting prelude.

Norman Maclean talked much of the loneliness of writing, but he also relished what he called its social side, and he planned to acknowledge the help he had received in writing this story. His greatest debts are recorded in the story itself: to Laird Robinson, Bud Moore, Ed Heilman, Richard Rother-mel, Frank Albini, and other men of the United States Forest Service; to women of the Forest Service, among them Susan Yonts, Beverly Ayers, and Joyce Haley; and to the survivors of the Mann Gulch fire, Walter Rumsey and Robert Sallee. Maclean would have thanked dozens more.

In editing the manuscript, the Press has benefited from the advice, at various stages, of Wayne C. Booth, Jean Maclean Snyder, and John N. Maclean. Laird Robinson was Norman Macleans partner in his quest for the missing parts of the Mann Gulch story, and we thank him for helping the Press in the same spirit. We are grateful, too, for the assistance of Joel Snyder, Dorothy Pesch, William Kittredge, Wayne Williams, and Richard Rothermel. We especially thank Jean Maclean Snyder and John N. Maclean for entrusting Young Men and Fire to the University of Chicago Press and working with us to bring it to publication.

Black Ghost

Black Ghost

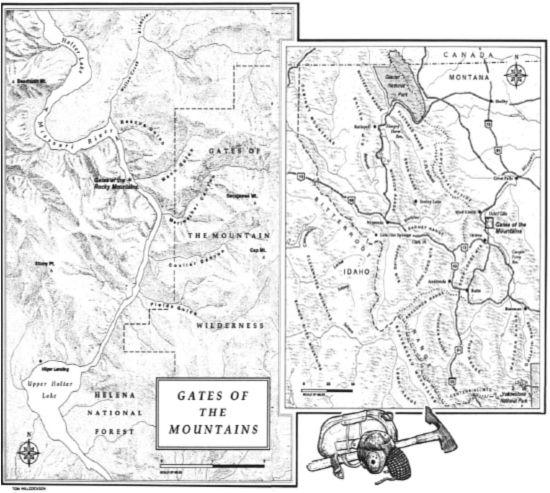

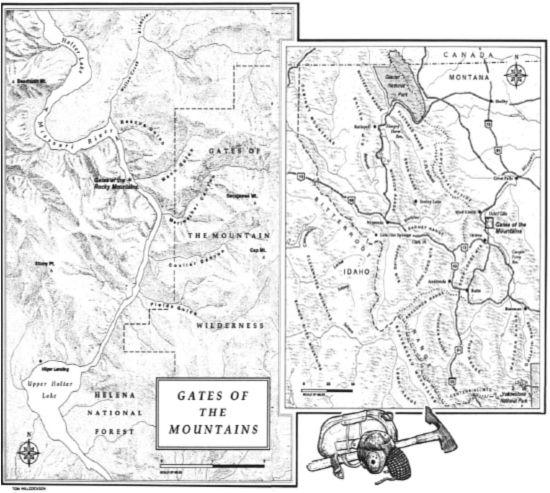

I T WAS A FEW DAYS after the tenth of August, 1949, when I first saw the Mann Gulch fire and started to become, even then in part consciously, a small part of its story. I had just arrived from the East to spend several weeks in my cabin at Seeley Lake, Montana. The postmistress in the small town at the lower end of the lake told me about the fire and how thirteen Forest Service Smokejumpers had been burned to death on the fifth of August trying to get to the top of a ridge ahead of a blowup in tall, dead grass. In the small town at Seeley Lake and in the big country around it there are only summer tourists and loggers, and, since the loggers are the only permanent residents, they have all the mailboxes at the post officethe postmistress, of course, has come to know them all, and as a result knows a lot about forests and forest fires in a gossipy way. Since she and I are old friends, I have a box, too, and every day when I came for my mail she passed on to me the latest she had heard about the dead Smokejumpers, most of them college boys, until after about a week I realized I would have to see the Mann Gulch fire myself while some of it was still burning.

I knew, of course, that a fire that big would be burning long after it had been brought under control. I had gone to work for the Forest Service during World War I when there was a shortage of men and I was only fifteen, four years younger than Thol, the youngest of those who had died in Mann Gulch, so by the time I was his age I had been on several big fires. I knew, for instance, that the Mann Gulch fire would be burning for a long time, because one November I had gone back with my father to hunt deer in country close to where I had been on a big fire that summer, and to my surprise I had seen stumps and fallen trees still burning, with smoke coming out of blackened holes in the snow.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.