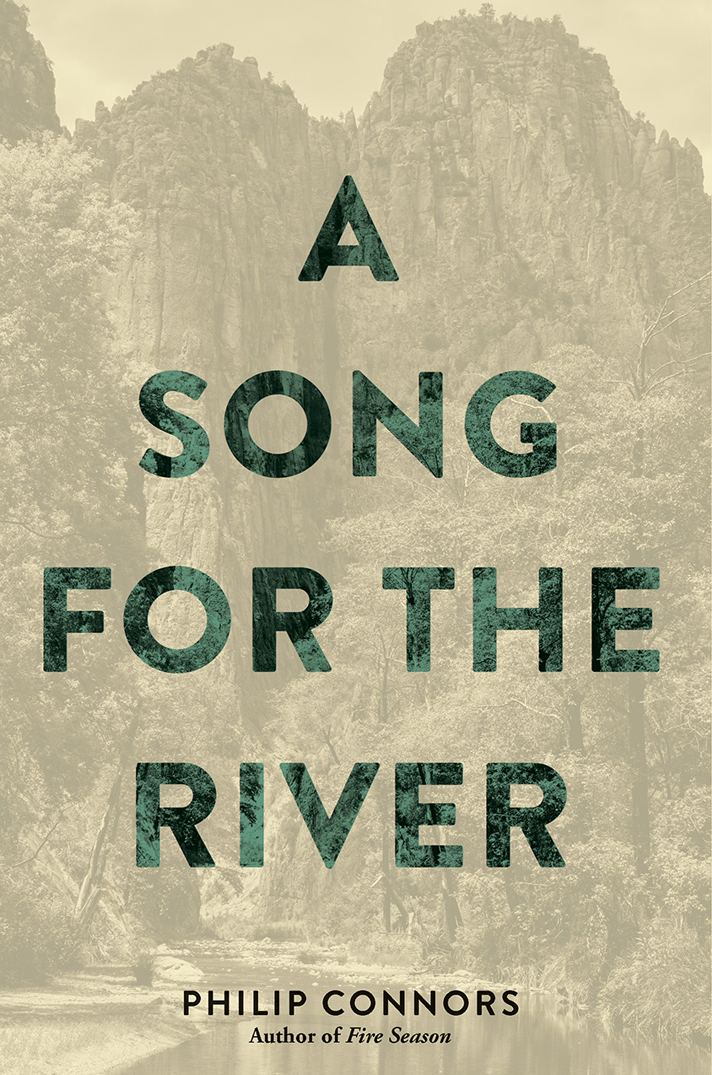

A Song for the River. Copyright 2018 by Philip Connors. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written consent from the publisher, except for brief quotations for reviews. For further information, write Cinco Puntos Press, 701 Texas Avenue, El Paso, TX 79901; or call 1-915-838-1625.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint copyrighted material:

Patrice Mutchnick and the estate of Ella Jaz Kirk for excerpts from the writings of Ella Jaz Kirk, including Cord Fluidity and A Prayer to the Raven, copyright 2018 by Ella Jaz Kirk.

Counterpoint Press for an excerpt from the poem The Lookouts, from Left Out in the Rain by Gary Snyder. Copyright 1986 by Gary Snyder. Reprinted by permission of Counterpoint Press.

FIRST EDITION

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Connors, Philip, author.

Title: A song for the river / by Philip Connors.

Description: First edition. | El Paso, Texas: Cinco Puntos Press, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017057947 | ISBN 9781941026922 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Connors, Philip. | Fire lookoutsNew MexicoGila National ForestBiography. | Gila National Forest (N.M.)

Classification: LCC SD421.25.C658 A3 2018 | DDC 634.9/61809789692dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017057947

Book and cover design by Anne M. Giangiulio

Cover photographs by Jay Hemphill

This is it! (Isnt that what you heard, Mary?)

Also by Philip Connors:

Fire Season: Field Notes From a Wilderness Lookout

All the Wrong Places: A Life Lost and Found

FOR MNICA

IN MEMORIAM

JOHN KAVCHAR

Signal Peak Lookout May 2012

ELLA SALA MYERS, MICHAEL SEBASTIAN MAHL, ELLA JAZ KIRK

Gila River April 2014

Like any Romantic, I had always been vaguely certain that sometime during my life I should come into a magic place which in disclosing its secrets would give me wisdom and ecstasy-perhaps even death.

Paul Bowles

The whole show has been on fire from the word go. I come down to the water to cool my eyes. But everywhere I look I see fire; that which isnt flint is tinder, and the whole world sparks and flames.

Annie Dillard

A river loves the water / that it can never keep.

Benjamin Alire Senz

Table of Contents

Guide

SUMMER 2016

AFTER ILLNESS and divorce did a number on my body and soul, after wildfires burned the mountains and an airplane fell from the sky, after a horse collapsed on my friend and two hip surgeries laid me up for the better part of a yearloss piled on loss, pain layered over painI found I wanted nothing so much as to be near moving water.

So I went once more to the river.

The river emerges from springs and ice caves high in the mountains and gathers rain and snowmelt from a watershed of nearly 2,000 square miles. For more than a decade I had kept watch over those mountains and found the experience a two-hearted deal, living amid calamity and resilience. In the beginning I simply wished to remove myself from human company. I had my reasons, not at all unusual. But I kept returning for the communion of creatures that made my mountain hum, a beautiful Babylon of owls hooting and nutcrackers jeering and hermit thrushes singing their small and lovely whisper songa palace of organisms, a heaven for many beings, a temple where life deeply investigates the puzzle of itself, as a wise man once said. The vultures, the ravens, the hawks, the Stellers Jays, the foxes and bears, the elk and deer, the salamanders in their holes, the ladybugs in their tens of thousands: all of them were part of the mountain, and so were death and rebirth.

To watch a mountain you love murmur and chirp and howl and green up from rain and bloom with flowers, then see it succumb to flame and be blackened by heat only to live once more from the ashes, was to absorb an object lesson in transience and renewal. From my perch above the shaggy pines and stately firs, I looked down on a world burning itself up, most of us burning ourselves up in work and striving and the peculiar game of consumption and accumulation without endthe whole world on fire from our appetites and their costand I sometimes thought it would not be a terrible fate to lie down for the last time in ashes, preferably on a mountain.

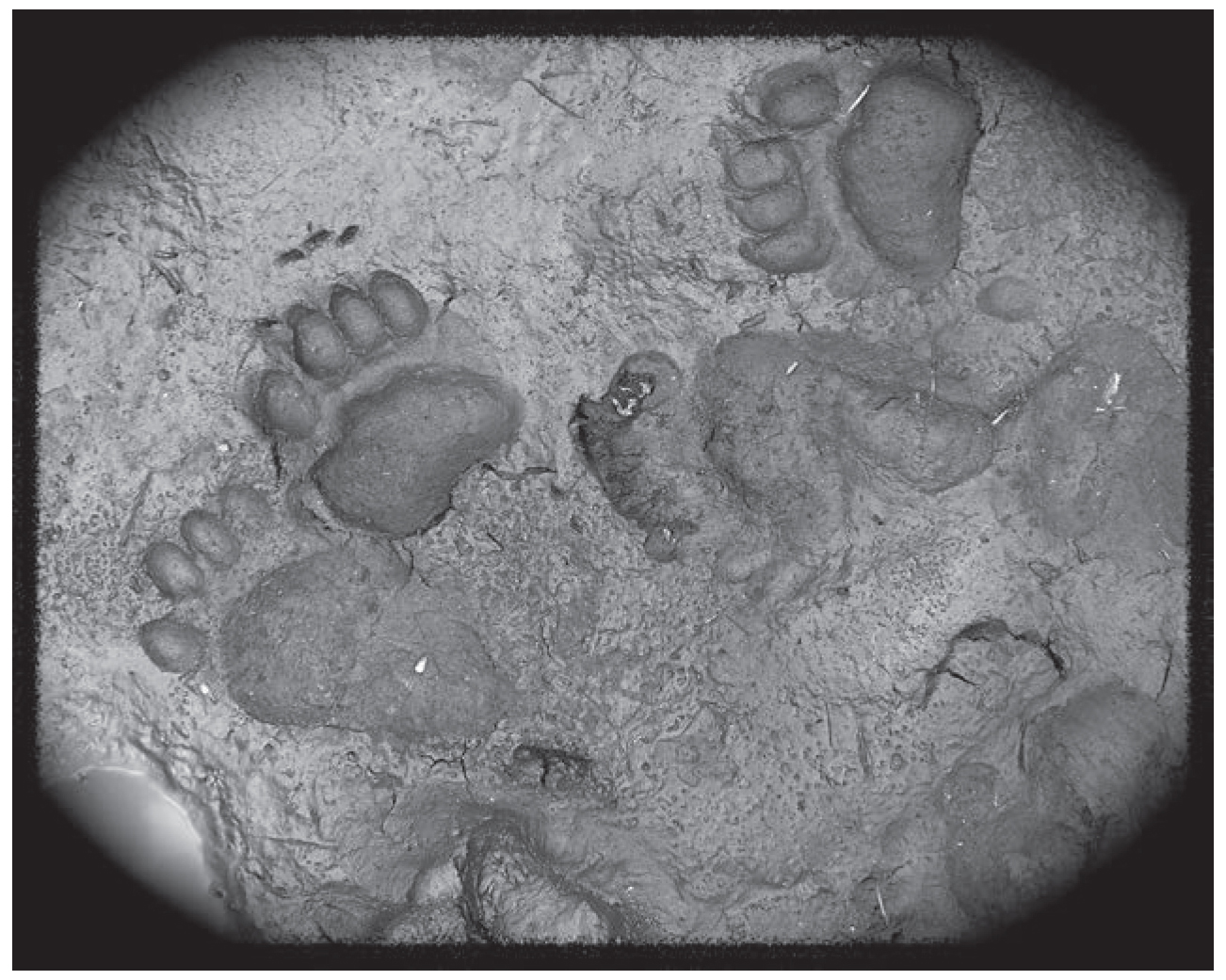

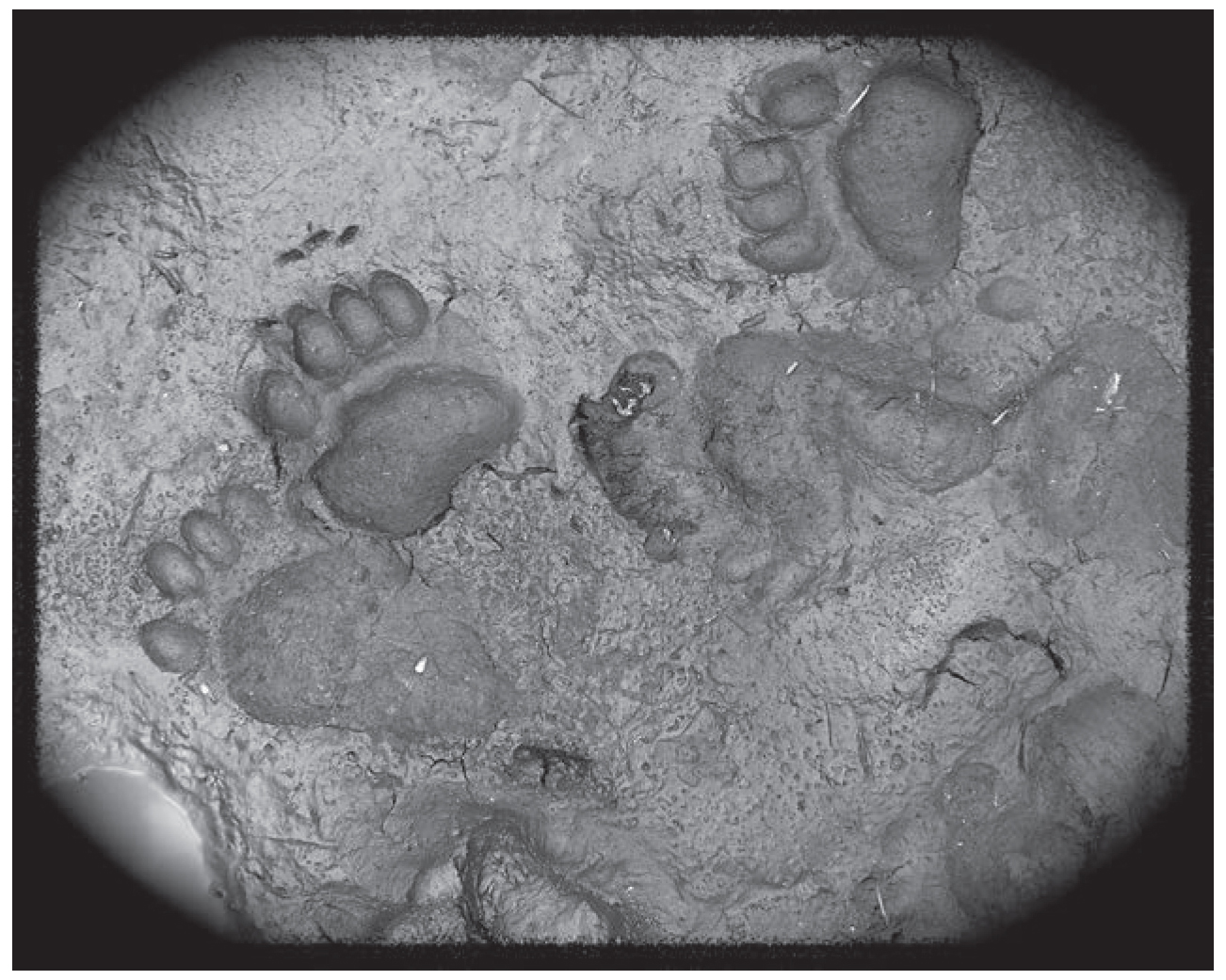

On a mountain, ashes do not remain still for long. They are worked on by wind and water and follow ancient courses decreed by the laws of hydrology, which are determined by the laws of gravity. When enough of these watercourses converge in a form that pulses and recedes but does not cease, we call the convergence a river. In the mud along the banks of the river, mud dappled by the pawprints of bears, were remnants not just of the forests in the mountains but of people I had loved and admired, and their remnants also arrived there having been transfigured by flame to ash.

The river drew its shape from volcanic upheavals thirty-five million years ago, and for untold millennia creatures have gone about their mysterious business along its floodplain and in the substrate of its waters. Some of the mysteries have been revealed to us, thanks to people who make it their business to interpret them. I spent time with a team of biologists in the river that summer, wading hip deep in the big pools, watching their stream-dance as they high-stepped with dip nets and seine nets and hauled up fish to measure and count before returning them to the water unharmed.

They spoke of things they had learnedfor instance how native loach minnows excavate a pocket beneath a flat rock in cobble. There the female lays her eggs for the male to fertilize. Being buoyant, the eggs adhere to the bottom of the rock. The male acts as the lookout over his progeny, cleaning away any fungus that attaches to the eggs and warding off insect predators and bottom-feeding desert suckers, until the eggs hatch and another generation takes its place in the weave of life that constitutes the river.

A threat hung over all this, another reason I went to the river. The threat appeared in the form of a concrete diversion dam that, if built, would put an end to the upper Gila River as a living entity. I wanted to find solace and strength in nearness to my friend John, a forest guardian while he lived, and my inspiration Ella Jaz, a river guardian while she lived, each of whom had gone before me in ash down the riverJohn after falling to his death beneath his horse, Ella Jaz after dying with her friends in the fiery wreckage of a plane. I wanted to hear, if I could, not just the voice of the river but the voices of my friend and inspiration, each of whom had known a thing or two about countering hubris and greed with logic and poetry. I wanted to pay homage to their memory as I rejoined the work of defending that sinuous green gallery of beauty from any attempt to defile it. I wanted to assure them we continued to speak up for the array of life that made the river singthe yellow-billed cuckoo and the willow flycatcher and the spikedace minnow and the narrow-headed garter snakein contrast to the bureaucrats, engineers, and county commissioners who uttered not an honest word in favor of the creatures that depended on the river, but instead sang hymns of praise to concrete berms, coanda screens, grouted boulder weirs, and prefabricated booster stations.