IMAGES

of America

FIRE LOOKOUTS

OF OREGON

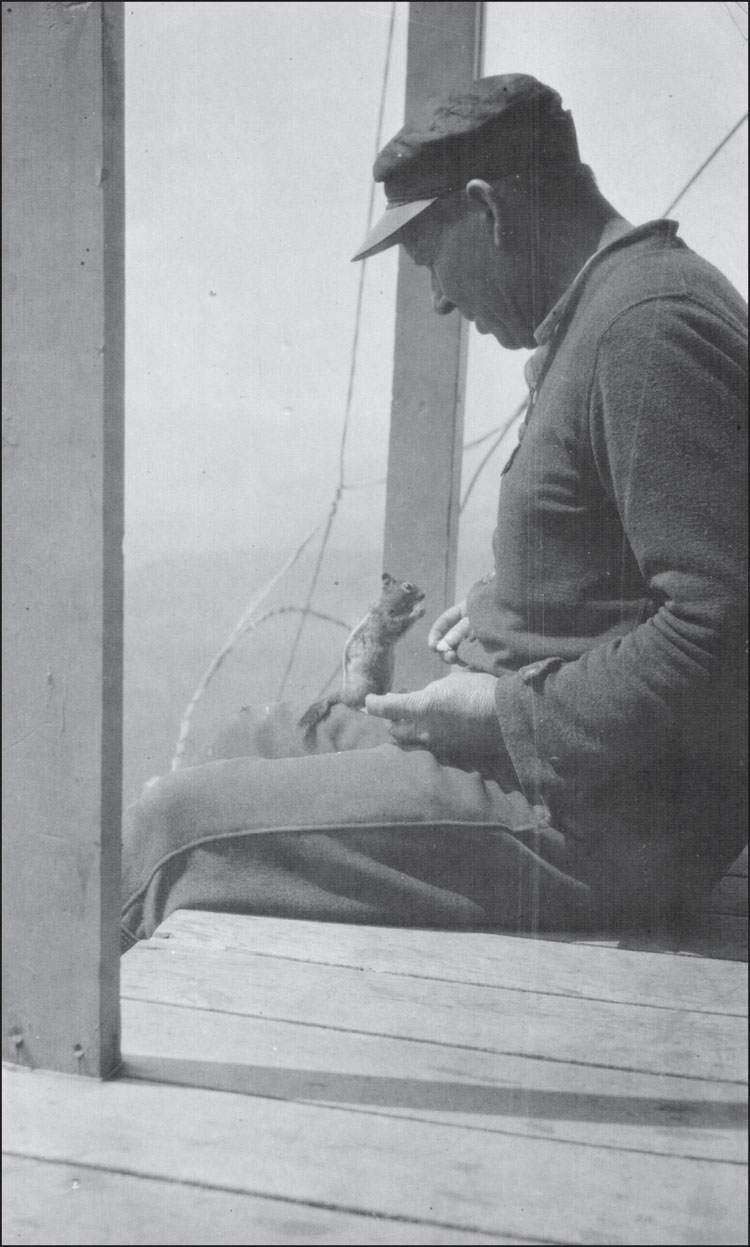

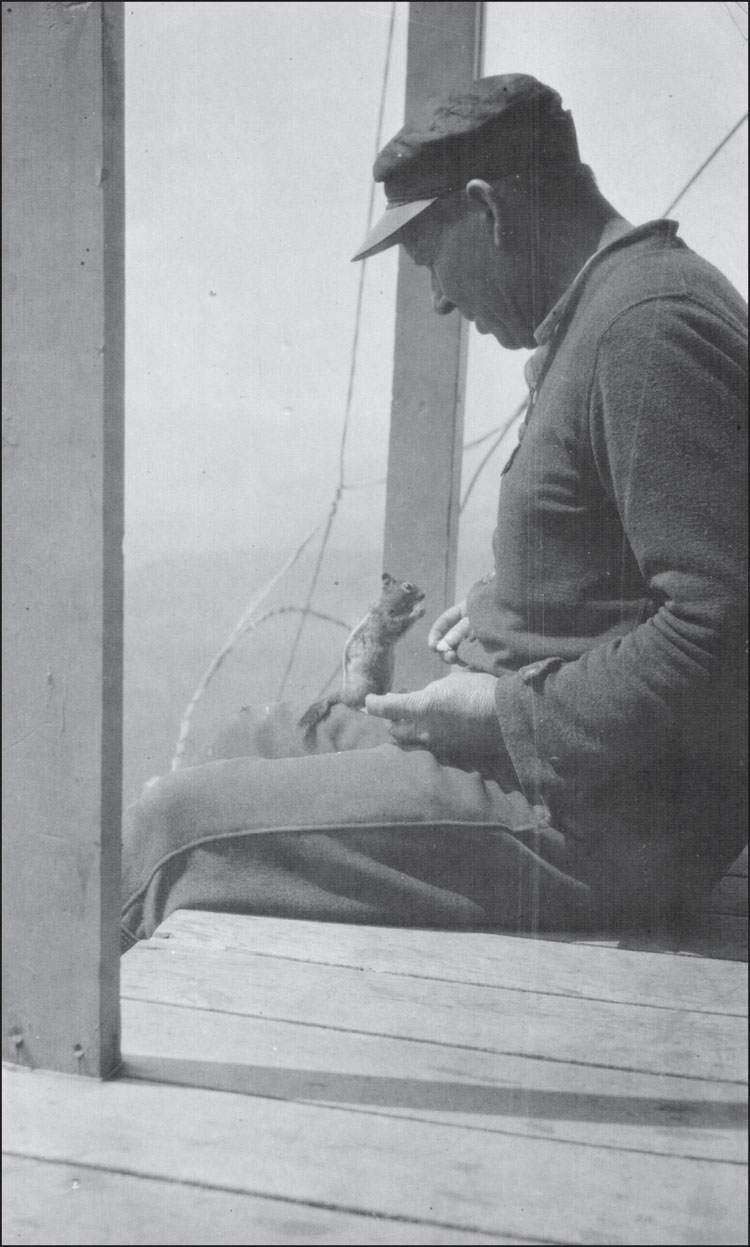

An unidentified man feeds a ground squirrel from the catwalk of a lookout. Some lookouts brought pets with them, but others often made friends with the local wildlife, especially ground squirrels, which are notorious beggars.

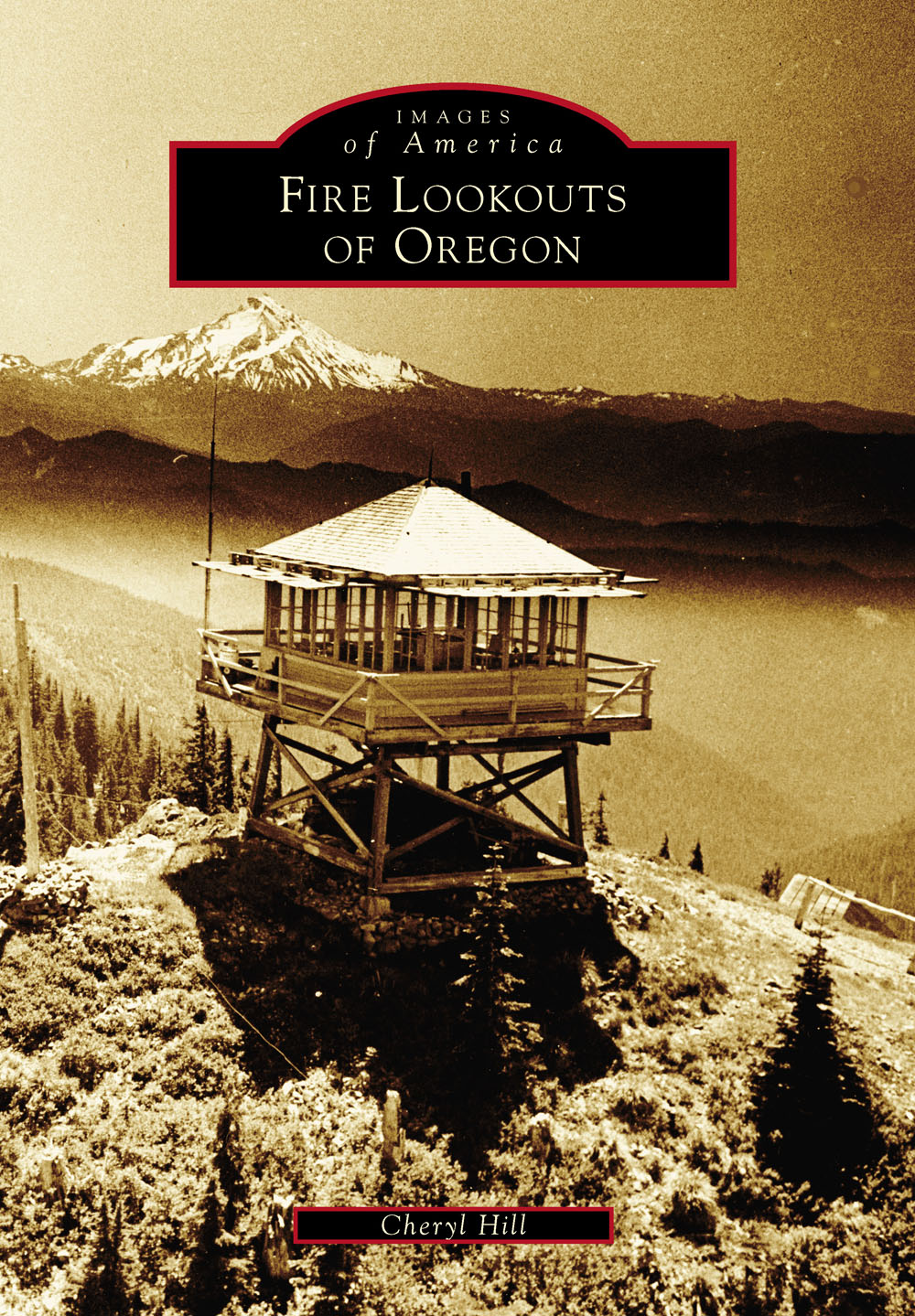

ON THE COVER: The Bull of the Woods lookout was built in 1942. The 10-foot-tall tower now sits at the heart of the Bull of the Woods Wilderness, which was created in 1984. It is the oldest of the seven lookouts still standing in the Mount Hood National Forest, although it is no longer staffed.

IMAGES

of America

FIRE LOOKOUTS

OF OREGON

Cheryl Hill

Copyright 2016 by Cheryl Hill

ISBN 978-1-4671-3486-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439655078

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015947044

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated to my parents, who nurtured my love of history.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

There are many lookout experts and enthusiasts out there, and I have been lucky enough to enlist the help of some of them. Thank you to Ray Kresek, Ron Kemnow, and Don Allen. Thank you also to La Vaughn Kemnow for your editing expertise.

Thank you to the history keepers at the national forest offices and other locations who took time out of their schedules to unearth boxes and albums of old photographs for me to scan and who shared their knowledge with me. Thank you to Debra Barner, Jacob Barnett, Denise Berkshire, Penni Borghi, Kevin Bruce, Sarah Crump, Chris Friend, Cathy Lindberg, Matthew Mawhirter, Patty McNamee, Jen Warren, and Alexandra Wenzl.

One of the joys of this project has been talking to the numerous people who were willing to share their stories with me. Thank you to all the people who spoke to me about your lookout experiences or those of your loved ones. I was not able to use all of your stories in the book, but I thank you all the same. Thank you to C. Rod Bacon, Roger Brandt, Lois Christiansen Eagleton, Annette Finger, Mary Frost, Bob Hanshaw, Donna Henderson, Randall Henderson, Mary Beth Hurlocker, Paul Ingram, Lee Jacobs, Gary Johanson, Donavin Leckenby, Patti Luse, Dee Lynch, Fred Merten, Richard Moles, John-Erik Nilsson, Bill Noland, Lindy Oleson, Benny Parmele, Dan Pinson, Jancy Potterf, Linda Shaw, Al Sorseth, Vicki Timm, and George Wynn.

Unless otherwise noted, all images in this book appear courtesy of the US Forest Service. Other images appear courtesy of the Oregon Department of Forestry (ODF), the Lane County Historical Museum (LCHM), the National Archives, the Forest History Society, Ron Kemnow, George M. Henderson, Bill Noland, Patti Luse, Linda Shaw, and the authors personal collection.

Wherever possible, I have named the people who appear in these images; however, most of the photographs did not include identification.

INTRODUCTION

When immigrants started settling the West in the last half of the 19th century, they began inhabiting vast forests. Millions of acres of trees were free for the taking. The 1891 Forest Reserve Act allowed the creation of forest reserves, much to the dismay of timber barons, mine owners, and railroad companies who felt they should be able to do what they wanted with the land. In 1905, the Bureau of Forestry became the US Forest Service, a federal agency that was now in charge of 60 million acres of forest.

The summer of 1910 was hot and dry. In August, numerous small wildfires in Idaho joined together to create what later became known as the Big Blowup. The young Forest Service lacked the funding and manpower to properly fight the fire, and a lack of trails and roads made access to the fire line difficult. When the fire was over, the eastern third of the town of Wallace had burned down, and three million acres of forest were torched. Records vary, but about 85 people were killed. Oregon did not escape unscathed that year. Fires burned all over the state, including a fire that burned more than 60,000 acres in the Crater National Forest (now called the Rogue RiverSiskiyou National Forest).

In the wake of that bad year, the Forest Service adopted a policy of strict fire suppression. In each national forest, a fire detection system was organized consisting of lookouts and guard stations. Early communication between these stations was rudimentary, involving heliographs, flags, or even carrier pigeons. These communication methods were soon replaced by a telephone system, which entailed hundreds of miles of No. 9 telephone wire strung throughout the forest. Maintaining these lines was a major job.

In 1911, Forest Service employee William Bush Osborne developed an alidade device, which would become known as the Osborne Fire Finder. It sat upon a stand in the center of the lookout and allowed observers to easily take a directional bearing (azimuth) if they spotted smoke. Using known landmarks near the smoke, they could report its approximate location. The Osborne Fire Finder was simple and effective and is still used today in fire lookouts.

Early lookouts were sometimes primitive, often just a crows nest high up a tree or a fire finder affixed to a mountaintop stump. Later, several different styles of lookouts were developed. They ranged from ground cabins to 100-foot-tall towers. There were D-6 cupola cabins, R-6 cabins, and steel towers with cramped seven-by-seven-foot cabs on top. One of the most common lookout styles was the L-4 model, a 14-foot square frame cabin that was bundled in kits and hauled to the site via pack trains. It was adaptable enough that it could sit on a foundation on the ground or perch atop a tower.

The men and women who were stationed at fire lookouts were also known as lookouts. Their primary duty was to regularly conduct a check look, inspecting their entire territory for smoke. Lookouts also checked the weather and reported back to headquarters. When they were not on duty or when the weather was bad, they caught up on chores, such as building maintenance, trail maintenance, chopping firewood, washing windows, and hauling water from the nearest spring, lake, or creek.

Starting around 1918, women started staffing lookouts alone. Many were schoolteachers or college students on summer break. Such a job being held by a woman was shocking to some at that time. A 1920 Oregonian article called the job harrowing for delicate women. But with billions of dollars worth of timber to protect from wildfire, the Forest Service was willing to hire able-bodied women to staff lookouts.

The 1930s was a boom decade for fire lookout construction. Some lookouts were built on private timberland and by the National Park Service, but most were built by the Forest Service. With the help of the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Forest Service built miles of new trails and roads to peaks and then packed or drove supplies to the summits for the lookouts. A vast network of lookouts sprang up during the Depression.

During World War II, fire lookouts briefly served a purpose other than identifying fires. The US Army established the Aircraft Warning Service (AWS) in 1941 with the goal of spotting enemy aircraft in American airspace and reporting it before significant damage could be inflicted. The system comprised more than 500 observation sites in Oregon, staffed by people who were not fit for service in the regular Army. This resulted in many women serving with the AWS. Observation posts had to be on alert all hours of the day and night year-round, so they were staffed in shifts. Many lookout sites doubled as AWS sites until the program was discontinued in 1944.

Next page