Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by Robert Sorrell

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.400.1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014956811

print edition ISBN 978.1.62619.817.3

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to thank the countless organizations, government agencies and people who have graciously contributed to this book, including, in no particular order, Lu Ellsworth of the High Knob Enhancement Corporation; Clinch Ranger District staff of the George Washington and Jefferson National Forest; Rabun County, Georgia Historical Society; Towns County, Georgia Historical Society; Union County, Georgia Historical Society; the Town of Unicoi, Tennessee; staff at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park; staff at the University of Tennessee Library and Great Smoky Mountains Regional Project; Charlie Roth, grandson of photographer Albert Dutch Roth; Friends of Great Smoky Mountains National Park; Tennessee Supreme Court justice Gary Wade; architect Tom Trotter; the staff at the Erwin Record newspaper; Phyllis Cline of Elizabethton, Tennessee; Betty Hodge of Bristol, Tennessee; Lisa Kestner Quigley of Hayters Gap, Virginia; Ron Stafford, Keith Argow and Krissy Reynolds, members of the Forest Fire Lookout Association; Tennessee State Library and Archives; National Register of Historic Places; Beth Bradford of New Jersey; the Morgan family of Bakersville, North Carolina; Doris Smithson Temple; Gale Colbaugh of Elizabethton, Tennessee; Rondall Ellis of Elizabethton, Tennessee; Lloyd Allen of Burnsville, North Carolina; Ted Wisniewski; Highlands, North Carolina Historical Society; Annie Laurie McDonald at the North Carolina Historic Preservation Office; Keith Peters; Interpretive Ranger Cathy Taylor at Paris Mountain State Park in South Carolina; staff at the South Carolina Forestry Commission; Virginia Department of Forestry; Friends of Cherokee National Forest; and Tusquitee Ranger District staff of the Nantahala National Forest.

I also want to thank the numerous people who have called me and sent e-mails and other correspondence with information and histories of fire towers. Lastly, thanks to the staff at The History Press for their support of this project.

INTRODUCTION

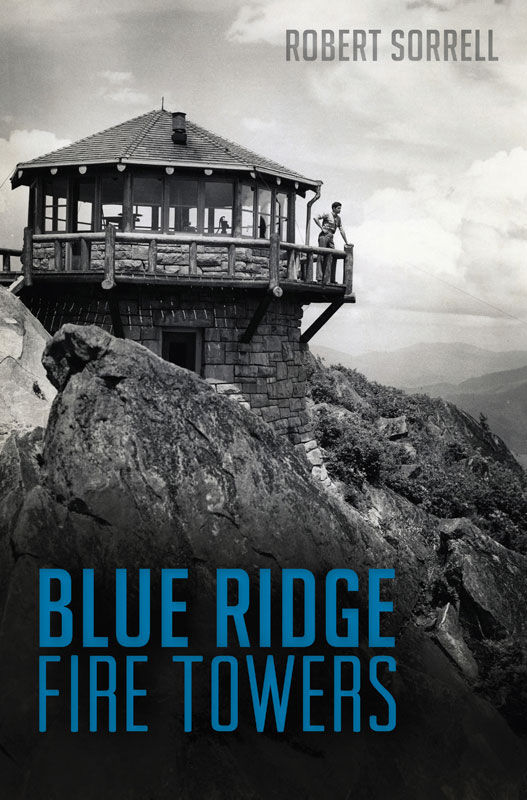

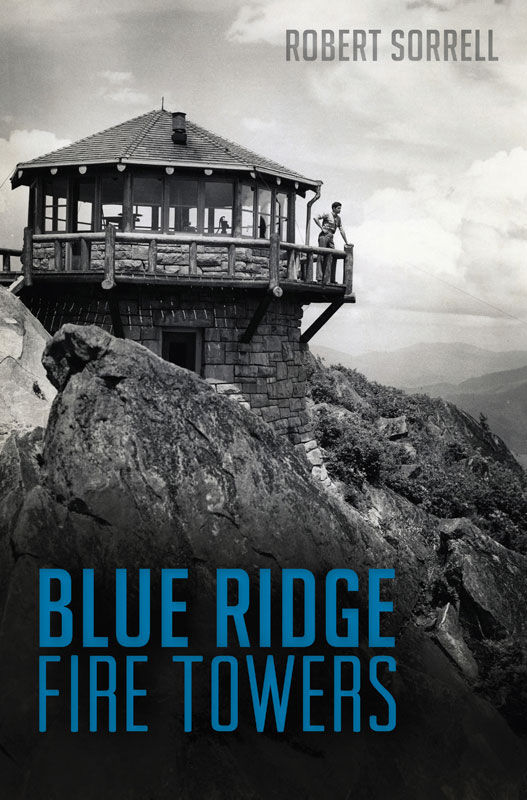

Keeping a watchful eye over the Blue Ridge Mountains in the eastern United States for more than a century, fire lookout towers have become icons in Americas great wild landscape. After decades of devastating wildfires that consumed millions of acres of forestland and communities across the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, conservationists created a network of fire lookout towers to protect the woodlands. They were designed so trained men and women, who manned the towers for days and weeks at a time, could spot flames and smoke from miles away. Using special fire finding equipment, such as the Osborne fire finder, lookouts would work together to pinpoint a fires location and communicate with headquarters to dispatch firefighters.

Working in solitude and sometimes high above the land in a small seven-by seven-foot wood box-like structure, lookouts became the eyes of the state and federal forestry departments. Lookout employees were, and still are, brave, smart and self-sufficient. They were also rapid and precise in spotting smoke, so firefighters could quickly venture into the mountains and douse the flames. They worked alone, not only watching for fires but also recording weather data, maintaining communications and greeting random hikers and tourists.

Lookout platforms, from which employees watch for smoke, come in all shapes and sizes. The earliest lookouts, those built before and shortly after 1900, included mountaintop tents, cabins and makeshift, temporary towers. Wood, steel and stone towers, typical of lookouts remaining today in the Blue Ridge, came later, primarily during the Great Depression era of the 1930s. Sometimes lookouts required no structure at all. A man or woman would simply stand at the highest point on a mountain and watch for smoke or flames with a pair of binoculars and the means to communicate with firefighters. Some lookout structures were also built in trees. A ladder would be attached to the side of a tall tree, and a seat or platform would be constructed near the trees top.

Over the years, temporary towers have been replaced with permanent towers. A small makeshift tower would be torn down and replaced with a large steel tower. In many cases, especially since the late twentieth century, towers have been taken down and replaced with nothing at all.

And while lookouts come in all shapes and sizes, many of the structures in the Blue Ridge are tall, sleek towers, rising above the balds and ridges of the mountains. These are the structures that give visitors with weak stomachs and frail nerves a case of the heebie-jeebies. Connie Miller of Blount County, Tennessee, recalled a visit to the old steel Look Rock Tower in the Great Smoky Mountains back in the late 1950s. She made the mistake of climbing the tower and looking back down from the lookouts cab. She froze. Thankfully, she was not alone, and her friends helped her back down the tower.

Government agencies, conservation organizations, businesses and private individuals have built thousands of lookout towers across the country. Idaho, with nearly one thousand towers, had more than any other state. According to the U.S. Forest Service, the state had fewer than two hundred towers in 2014. Kansas is the only state to have never had a lookout tower. Most towers built in the United States were constructed between the 1930s and 1940s. There were lookouts in the late nineteenth century, but none remains today. Lookout towers, although not generally used for fire watching, are still built today, if only for tourism.

The first known tower for forest fire detection in the United States was built in 1902 on private lands in Idaho. The Forest Lookout Museum said that the 1902 site was a woman who climbed a makeshift ladder and sat on a big tree limb at Bertha Hill, Idaho.

An even earlier fire lookout was constructed in Helena, Montana, but it was especially built to warn citizens of fires in the town. The Guardian of the Gulch Fire Tower was originally built in 1874 and had a bell to warn citizens of fire. The tower still stands over Helena and has had several repairs over the years.

The U.S. Forest Service built its first fire tower in 1915 in Oregon. The first tower in the eastern United States was built in the Adirondack Mountains of New York in 1909. The first full-time female fire lookout was hired in 1914.

Although fire lookouts were used as early as 1900 in the Blue Ridge Mountains, towers started to be constructed in the 1910s. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), two postGreat Depression government agencies, built a vast majority of the towers in the Blue Ridge and elsewhere in the country. Young unemployed men enlisted by the thousands, lived in CCC camps, similar to military barracks, and worked hard labor. The CCC worked with the U.S. Forest Service, the National Park Service, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the Bureau of Land Management on various projects, including the construction of fire towers and firefighting.

Next page