Sei Shonagon - The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon

Here you can read online Sei Shonagon - The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Tuttle, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

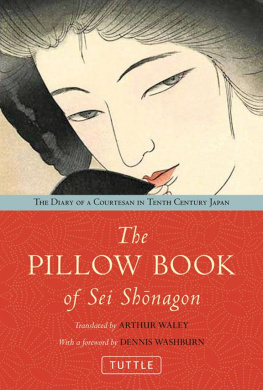

- Book:The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon

- Author:

- Publisher:Tuttle

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The

PILLOW BOOK

of Sei Shnagon

THE DIARY OF A COURTESAN IN TENTH CENTURY JAPAN

Translated by ARTHUR WALEY

With a foreword by DENNIS WASHBURN

TUTTLE Publishing

Tokyo | Rutland, Vermont | Singapore

To Hazel Crompton

Published by Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Copyright 2011 Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

Credit Images used with the permission of The Clark Center for Japanese Art & Culture

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sei Shonagon, b. ca. 967.

[Makura no soshi. English]

The pillow book of Sei Shonagon: The Diary of a Courtesan in Tenth Century Japan / translated by Arthur Waley; with a foreword by Dennis Washburn.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4629-0088-6

1. Sei Shonagon, b. ca. 967. 2. Courtesans--Japan--Biography. 3. Japan--Court and courtiers--Biography. 4. Japan--Court and courtiers--History. 5. Japan--Social life and customs--794-1185. 6. Japan--History--Heian period, 794-1185. I. Waley, Arthur. II. Title.

PL788.6.M3E56 2011

895.68103--dc22

[B]

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010026057

ISBN 978-1-4629-0088-6

Distributed by

North America, Latin America & Europe

Tuttle Publishing

364 Innovation Drive

North Clarendon, VT 05759-9436 U.S.A.

Tel: 1 (802) 773-8930; Fax: 1 (802) 773-6993

info@tuttlepublishing.com

www.tuttlepublishing.com

Asia Pacific

Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd.

61 Tai Seng Avenue #02-12

Singapore 534167

Tel: (65) 6280-1330; Fax: (65) 6280-6290

inquiries@periplus.com.sg

www.periplus.com

Japan

Tuttle Publishing

Yaekari Building, 3rd Floor

5-4-12 Osaki, Shinagawa-ku

Tokyo 141 0032

Tel: (81) 3 5437-0171; Fax: (81) 3 5437-0755

sales@tuttle.co.jp

www.tuttle.co.jp

First edition

14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in Singapore

TUTTLE PUBLISHING

is a registered trademark of Tuttle Publishing, a division of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

Foreword

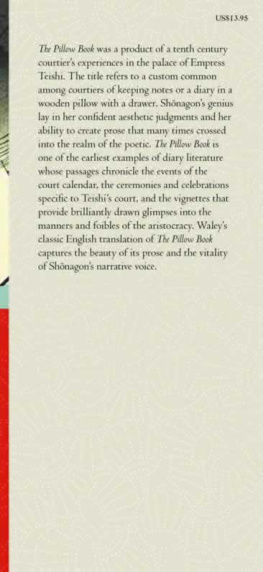

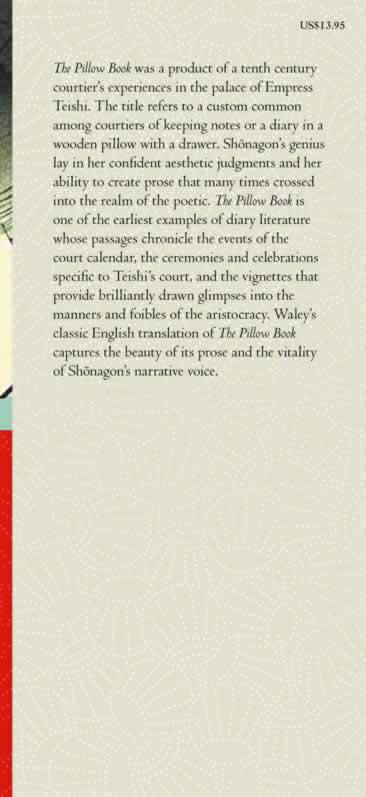

Arthur Waleys translation of Sei Shnagons The Pillow Book ( Makura no s shi ), which was first published in 1928, may strike contemporary readers as something of a literary curiosity. Waley informs us at the very beginning of his work that he has translated only about one-quarter of the original, omitting only those portions (i.e. a full three-quarters of the text) he found dull, unintelligible and repetitive, or that required too much explanation. Moreover, he does not provide a straightforward, stand-alone translation, but instead offers a mix of translated passages and commentary that contextualizes and explains the original text. These extraordinary decisions not only imply a rather severe critical judgment of the literary value of Sei Shnagons work, but also suggests in a somewhat backhanded manner that his English-speaking readership had neither the patience nor the imagination to deal with the original in its entirety.

At first glance Waleys approach seems to fly in the face of one of the most fundamental assumptions about translation, which is that it must somehow stay true to the original and preserve its integrity. To make radical cuts on the basis of practical considerations of length or intelligibility is an understandable though debatable proposition, but to select which passages to translate on the basis of subjective criteria (e.g. what makes one section dull and another interesting) is simply arbitrary. However, by the same token, to criticize Waley solely on the basis of the notion that the translator must preserve the integrity of a text, that he should essentially disappear from view so that the reader can engage the original without mediation, is also very much a debatable proposition, since determining what it means to stay true to an original almost always depends upon subjective criteria. In producing his version of The Pillow Book, Waley was certainly as much an editor as a translator, and as such his work challenges widely accepted notions of the role of the translator. In order to judge his work fairly, to account for its strengths and weaknesses, we need to consider the validity of the reasons behind his choices.

In 1928, Waley undertook his translation of The Pillow Book during a remarkably productive period of his life. He had begun his studies of Chinese and Japanese in 1913 after taking a position cataloguing the British Museums Oriental Prints and Manuscripts collection, and he started his career as a translator a few years later with a focus on Chinese poetry a project that led to a brief professional association with Ezra Pound. Following on from his work with Chinese literature, he spent over a decade translating Murasaki Shikibus The Tale of Genji , eventually publishing his version in six volumes between 1921 and 1933. The acclaim he received secured his reputation as both a writer and a scholar, and established him as a seminal figure in the history of Japanese cultural studies in the West.

Given the demands placed on him by his other projects, Waleys decision at that time to turn his attention to The Pillow Book seems extraordinarily ambitious. He certainly had personal reasons to undertake the project, since his success helped create a readership for translations from Asian literatures. There was, however, a compelling historical justification for the project as well. Shnagons work has been considered canonical in Japan for a millennium, and it is usually placed alongside Murasakis masterpiece as one of the most of important achievements of the aristocratic culture of the Heian court. Taking that shared history into account, the value and appeal of translating The Pillow Book simultaneously with The Tale of Genji is apparent.

Comparisons between these works are sometimes a bit forced, since they are in fact quite different in form and conception. However, there was a long history in Japan of linking the works less on the basis of literary considerations than on the perception of a personal rivalry between the two authorsa rivalry occasionally expressed as a contrast between personalities, with Shnagon being (supposedly) bright, perky, and audacious and Murasaki being dour, melancholy, and profound. While there is some textual basis for claiming this difference in temperament, any conclusions about the personal lives of these women remain speculative. What is not speculative is that they both employed their literary talents in the service of empresses who in fact were political rivals; and while Shnagon and Murasaki may not have been in direct competition (though it is clear from Murasakis diary that they were aware of one another) their literary works were produced in a cultural milieu that privileged highly refined aesthetic sensibilities. In that respect their writings were shaped by and provide vivid insight into the values that governed taste and behavior in aristocratic society.

Waley makes it clear in his introductory essay that he believed the most important connection between The Pillow Book and The Tale of Genji was this shared aestheticism, and he makes a number of sweeping generalizations about Japanese court culture to support his claim. He argued that it was a culture that lacked any true historical awareness, that courtiers were so absorbed in the present that the term modern always denoted a positive value. As a result, he sees in mid-Heian court culture a kind of intellectual passivity and an obsession with proper form and ritual that led the aristocracy to place great emphasis on aesthetic pursuits.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon»

Look at similar books to The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.