Japan in the Tenth Century

W HEN the first volume of The Tale of Genji appeared in English, the prevailing comment of critics was that the book revealed a subtle and highly developed civilization, the very existence of which had hitherto remained un-suspected. It was guessed that so curious a state of society, with its rampant stheticism and sophisticated unmorality, its dread of the explicit, the emphatic, must have behind it a protracted history of undisturbed development, or (as others put it) must be the climax of an age-long decadence.

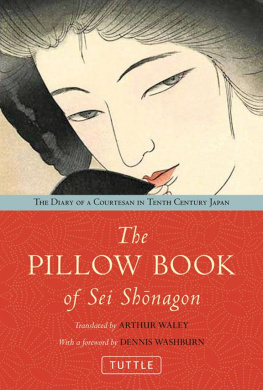

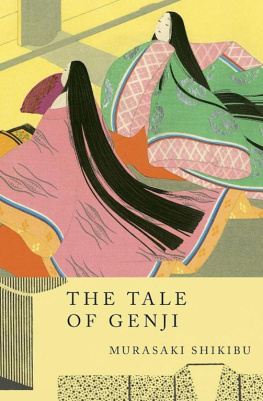

And it is indeed true that the unique civilization portrayed in The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book of Sei Shnagon corresponds to a unique record of isolation and tranquillity. The position of Japan, lying on the edge of the Oriental world, has been compared to that of England always in full communion with Europe, yet exempt from the worst perils of contiguityin fact, ideally semi-detached.

But the comparison has little force. Japan is eight times farther from the mainland than we from France. One cannot swim across the Straits of Tsushima. Yet phase after phase of civilizationagriculture, tools, domestic animals at an age long before history, then later, the Chinese ideograms, Indian religion, Persian textilesmanaged to filter across the Straits; while invasion, save for an occasional raid of pirates from China, not merely during those early years, but until the abortive Mongol descent in the thirteenth century, was almost unknown. In Europe and on the continent of Asia no single strip of land has ever enjoyed a like immunity. Across France, Hungary, Poland, Turkestan, how many armies marched during the long centuries of Japans absolute security! Thus arose a culture that, among other peculiarities, had that of not being cosmopolitan. Rome, Byzantium, Ctesiphon, even Chang-an were international cities. In the streets of Kyto a stray Korean or Chinaman was, as specimens of the exotic, the best that could be hoped for. The world, to a Japanese of the tenth century, meant Japan and China. India was semi-mythical, and Persia uncertainly poised somewhere between China and Japan.

Thus, since the establishment of the capital at Heian in 794, had grown up a highly specialized, intense and uniform civilization, dominated by one family, the Fujiwara; a state of society in which the stock of knowledge, the experience, the prejudices of all individuals were so similar that the grosser forms of communication seemed no longer necessary. A phrase, a clouded hint, an allusion half-expressed, a gesture imperceptible to common eyes, moved this courtly herd with a facility as magic as those silent messages that in the prairie ripple from beast to beast.

It was a purely sthetic and, above all, a literary civilization. Never, among people of exquisite cultivation and lively intelligence, have purely intellectual pursuits played so small a part. What strikes us most is that the past was almost a blank; not least so the history of Japan, extending even in mythological theory only to the seventh century B.C. and remaining fabulous for fifteen hundred years.

It is indeed our intense curiosity about the past that most sharply distinguishes us from the ancient Japanese. Here every educated person is interested in some form or another of history. The busiest merchant is an authority upon snuff-boxes, Tudor London, or Chinese jade. The remotest country clergyman reads papers on eoliths; his daughters revive forgotten folk-dances. But to the Japanese of the tenth century, old meant fusty, uncouth, disagreeable. To be worth looking at a thing must be imamekashi , now-ish, up-to-date. By Shnagon and Murasaki the great collection of early poetry (the Manysh ), on the rare occasions when they quote it, is always referred to in an apologetic way, as something that, despite its solid merits, will necessarily offend the modern eye. Nor did they feel that the futurewith us an increasing preoccupation in any way concerned them.

Their absorption in the present, the fact that with them modern was invariably a term of praise, differentiates them from us in a way that is immediately obvious. The other aspects of their intellectual passivitythe absence of mathematics, science, philosophy (even such amateur speculation as amused the Romans was entirely unknown)may not seem at first sight to constitute an important difference. Scientists and philosophers, it is true, exist in modern Europe. But to most of us their pronouncements are as unintelligible as the incantations of a Lama; we are mere drones, slumbering amid the clatter of thoughts and contrivances that we do not understand and could still less ever have created. If the existence of contemporary research had no influence except upon those capable of understanding it, we should indeed be in much the same position as the people of Heian. But, strangely enough, something straggles through; ideas that we do not completely understand modify our perceptions and hence refashion our thoughts to such an extent that the society lady who said, Einstein means so much to me was expressing a profound truth.

It is, then, not only their complete absorption in the passing moment, but more generally the entire absence of intellectual background that makes the ancient Japanese so different from us, and gives even to the purely sthetic sides of their culture a curious quality of patchiness. At any moment these men and women, to all appearances so infinitely urbane and sophisticated, may surprise us, even where matters of taste rather than intellect are concerned, by lapsing into a niaiserie far surpassing the silliness of our own Middle Ages. It is this insecurity which gives to the Heian period that oddly evasive and, as it were, two-dimensional quality, its figures and appurtenances seeming to us sometimes all to be cut out of thin, transparent paper.

Religious ceremonies were much in vogue, but were viewed chiefly from an sthetic standpoint. The recitation of sacred texts was an art practiced by the laity as well as the clergy. An exacting standard of connoisseurship prevailed, and if Buddhist services were packed to overflowing, it was upon appraising the merits of the performers rather than upon his own spiritual improvement that a Heian worshipper was bent.

Mimes, pageants, processions filled the Court calendar. Those organized by the Church had a certain tinge of exotic solemnity; for until the tenth century, Indian Buddhism continued to send out fresh waves of influence, which now reached China (and hence Japan) less circuitously than in former days.

But it would scarcely be an exaggeration to say that the real religion of Heian was the cult of calligraphy. Certainly writing was the form of conduct that was scrutinized most severely. We find beauty of penmanship not merely counting for almost as much as beauty of person, but spoken of rather as a virtue than as a talent, and the epithet good, when applied to an individual, frequently refers not to conduct but to handwriting. Often in Japanese romances it is with some chance view of the heroines writing that a love-affair begins; and if the hero happens to fall in love with a lady before he has seen her script, he awaits the first traces of her hand with the same anxiety as that which afflicted a Victorian gentleman before he had ascertained his fiances religious views. It was as indispensable that a Japanese mistress should write beautifully as that Mrs. Gladstone should be sound about the episcopal succession.