Appendix

The Heain Setting: Illustrations

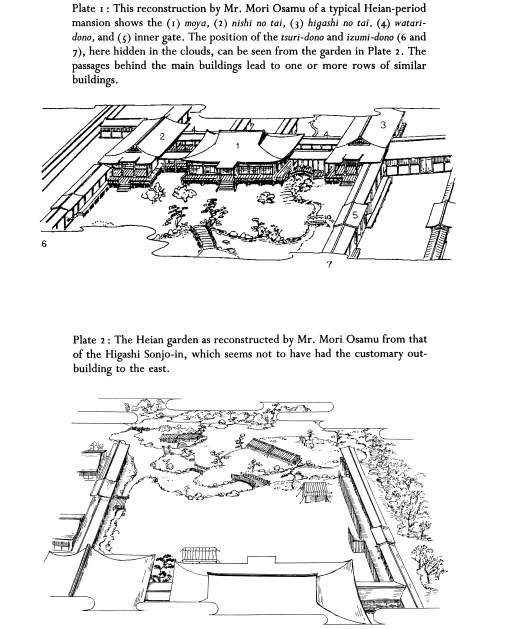

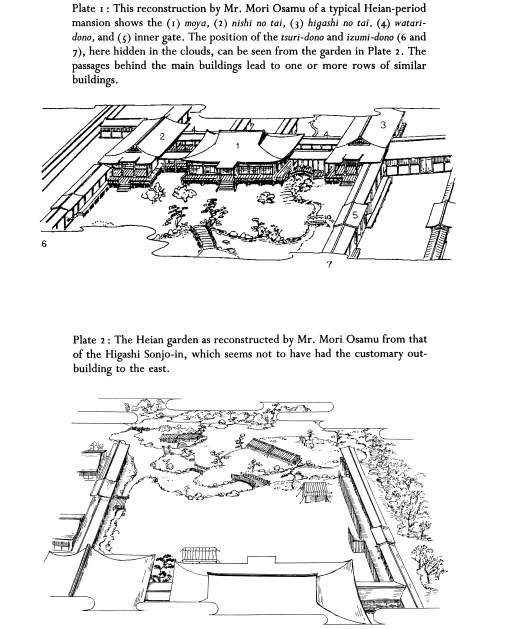

1. The shinden -style Heian mansion

. Panoramic view of the Heian garden

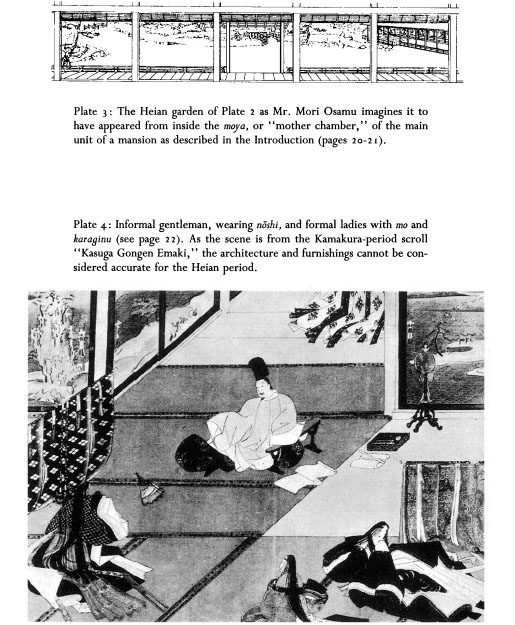

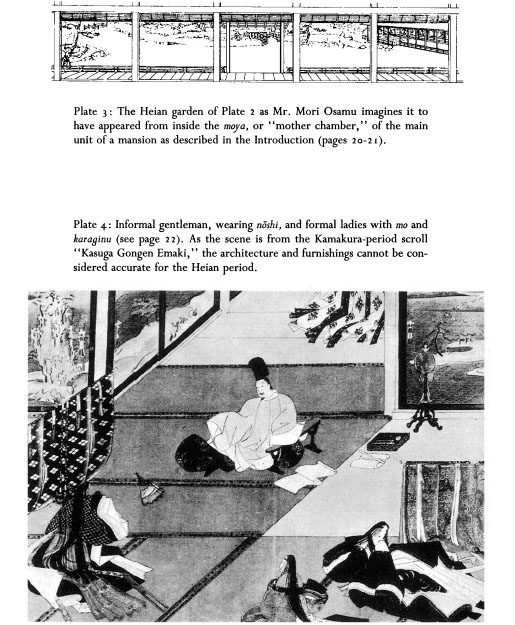

The Heian garden viewed from inside a mansion

Heian courtiers in formal and informal dress

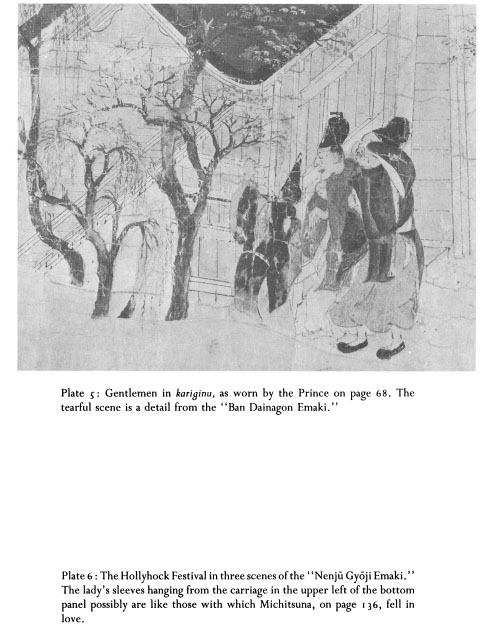

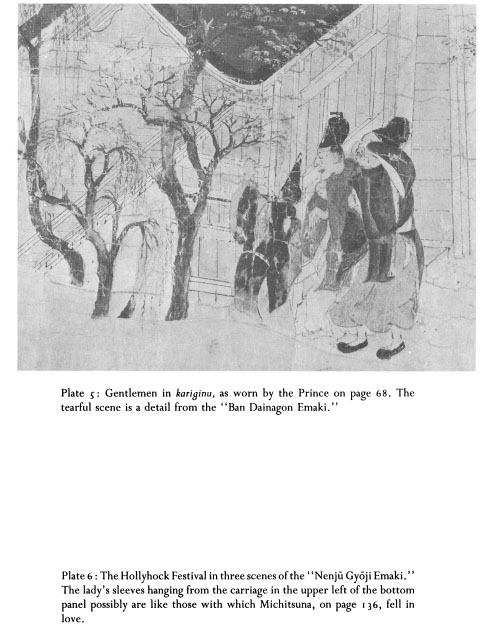

Gentlemen attired in kariginu

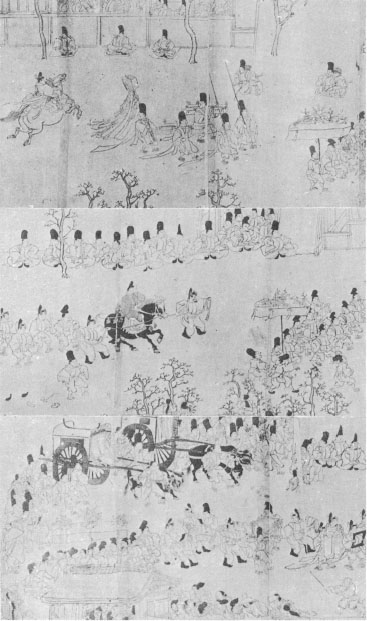

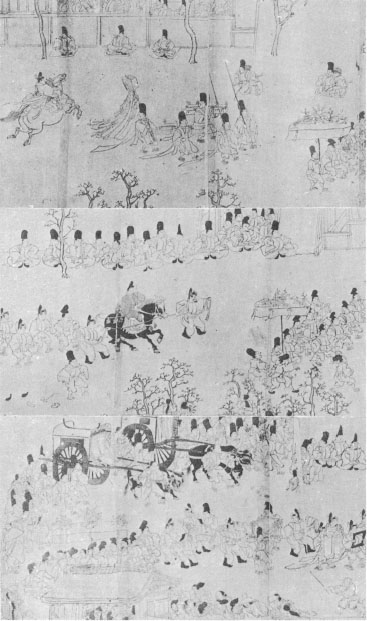

Scenes from the Hollyhock Festival

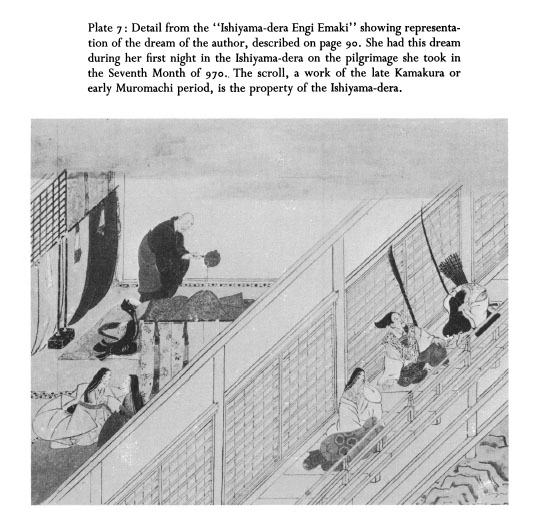

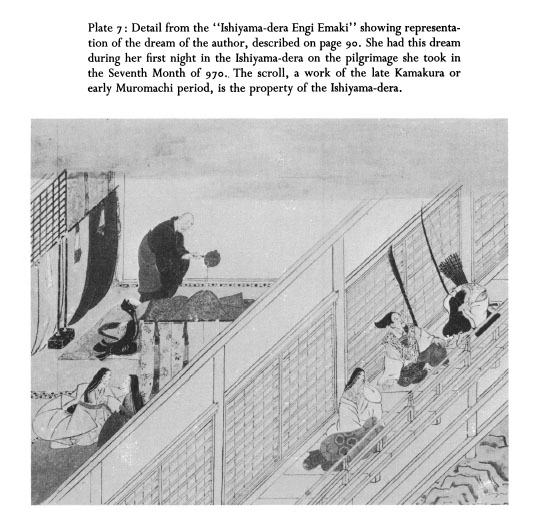

Detail from the Ishiyama-dera Engi Emaki

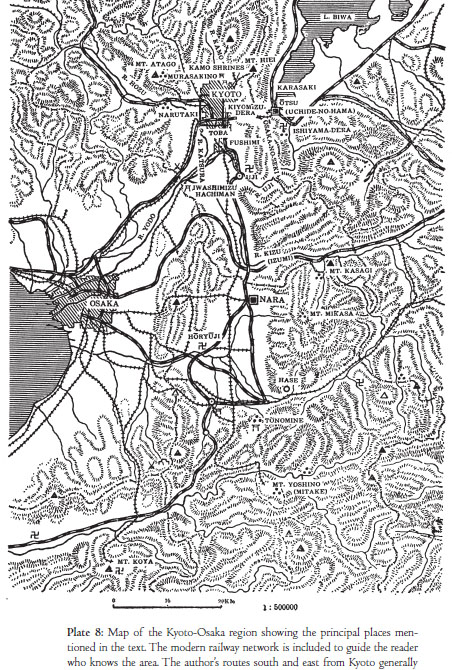

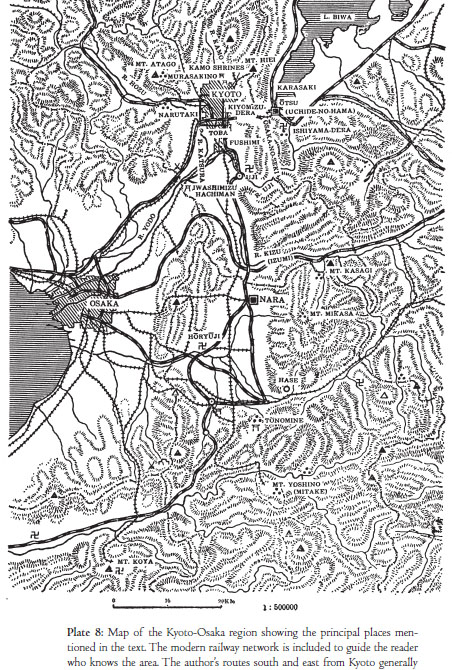

Map of the Kyoto-Osaka Region

Book One

Book One

THESE times have passed, and there was one who drifted uncertainly through them, scarcely knowing where she was. It was perhaps natural that such should be her fate. She was less handsome than most, and not remarkably gifted. Yet, as the days went by in monotonous succession, she had occasion to look at the old romances, and found them masses of the rankest fabrication. Perhaps, she said to herself, even the story of her own dreary life, set down in a journal, might be of interest; and it might also answer a question: had that life been one befitting a well-born lady? But they must all be recounted, events of long ago, events of but yesterday. She was by no means certain that she could bring them to order.

The Eighth Year of Tenryaku (954)

The Eighth Year of Tenryaku (954)

I SHALL not touch upon the frivolous love notes I had received from time to time. Now the Prince was beginning to send messages. Most men would have gone through a suitable intermediary, a lady in waiting perhaps, but he went directly to my father with hints, possibly half-joking at first, that he would like to marry me; and even after I had indicated how inappropriate I found the idea he sent a mounted messenger to pound on my gate. I scarcely needed to ask who it was. With the house in an uproar, I finally had to take the message, though I would have preferred to refuse it. My women only became noisier.

It consisted of but one verse: "Sad am I,'mid talk about the warbler. May not I too hear its voice?"

The paper was rather unbecoming for such an occasion, I thought, and the handwriting was astonishingly bad. Having heard that he was a most accomplished penman, I wondered indeed whether he might not have had someone else write it.

I was half-inclined not to answer, but my mother insisted that a letter from such a gentleman was not to be ignored, and finally I sent off a return poem: "Let no bird waste its song in a wilderness where it finds no answer."

That was the beginning. There came other poems, but I let them go unanswered. There was this, for instance: "Shall I liken you to the noiseless waterfall of Yamashiro? And when, I wonder, do we come to the pleasanter shallows?" I continued to turn his messengers back with promises that I would answer later, until my mother was aroused to action by this piece of doggerel:

"Perhaps now, perhaps now, I whisper to myself. But you do not answer. I am left desolate."

"You cannot continue to ignore such a man," she said. "You must stop being so kittenish."

And so I had one of my ladies compose a poem, suitable but hardly warm, and even at this secondhand reply he seemed delighted. I was besieged with poems. One of them suggested that my failure to write my own letters probably told of other and more interesting suitors:

"The plover's tracks are gone from the beach. Is it that the waves are higher now?" This too I answered by proxy.

"The sincere tone of your notes is as I would have it," he remarked at the end of one rather earnest letter, "but if you persist in having someone else write them I must conclude that you are heartless. 'Two of you there are, and I hesitate to choose between you; but let me now hear from her who has scorned to show herself.'"

Still I declined to answer directly, and we continued to correspond on into the autumn without entering into a more serious relationship. And then I finally sent my own reply to this one:

"I suspect that someone is interfering. I have tried to remain calm, but how is it that,'though my village lies quiet, untroubled by the calls of the night-wooing deer, my nights are sleepless?'"

"This last statement of yours is indeed strange," I answered. '"Even in the mountains above Takasago, one hears, they sleep well despite the deer.'"

And again, somewhat later, he wrote:

The barrier of Osaka, the gate to pleasant meetings,

Is so very near and yet, alas, so difficult to cross.

I answered with a similar word play:

Well may you speak of Osaka, which summons and forbids.

But what of famous Nakoso, that Barrier "Come-not-my-way?"

And so the letters went, and then one morning-when might it have been? -he sent me this verse: "Like the River Oi awaiting a flow of logs, my tears pour on as I await the eve."

And I answered: '"Countless as the logs upon the Oi are my misgivings; and, try though I may to stop them, my tears outflow the river.'"

Two mornings later came another poem: "I was swept away like the dew in the rising sun; and my heart seemed to die within me."

Again my answer: '"Powerless as the dew-how wretched that must be. But think of me, more feeble yet, made to rely on the dew!'"

The days went by. He came to visit me one evening when, for certain reasons, I was away from home, but he went back early the following morning and left behind this note: "I had hoped to spend at least today with you, but the indications are that this would not be convenient. Have you left me and become a hermit?"

I answered with but one verse: "The wild carnation in the alien hedge is broken and can no longer support the dew."

Toward the end of the Ninth Month he stayed away for two nights running and sent only a very hasty note by way of explanation. I replied in verse:

My sleeves still wet from last night's dew-then why

Must I wake to find another cloudy sky?

He sent back immediately:

Cloudy indeed. And shall I tell you why?

'Tis my troubled thoughts reflected in the sky.

He appeared before I had time to finish my answer.

Time passed. One rainy day, when I had not seen him for some time, he sent a messenger (or so I remember it) to say that he would visit me that evening.

"'In vain they look to the oak for protection,'" I answered.'"Night after night the rain drips through on the grasses under the grove."'

He came immediately, no doubt to avoid the bother of having to compose an answer.

Part of the Tenth Month I spent in penance, and this seemed to annoy him.

'"The sleeve of my turned-out robe is chill with tears,"' he wrote,'"and this morning even the heavens seem to weep.'"

I answered: '"Ah, but when one really loves, the warmth of one's thoughts should dry those turned-out sleeves.'"

Book One

Book One The Eighth Year of Tenryaku (954)

The Eighth Year of Tenryaku (954)