THIS BOOK WAS PUBLISHED WITH THE ASSISTANCE OF THE

Z. Smith Reynolds Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

1939 The University of North Carolina Press

Commentary by Benjamin Filene 2019 Benjamin Filene

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Set in Miller and Real Head Pro types by Rebecca Evans

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

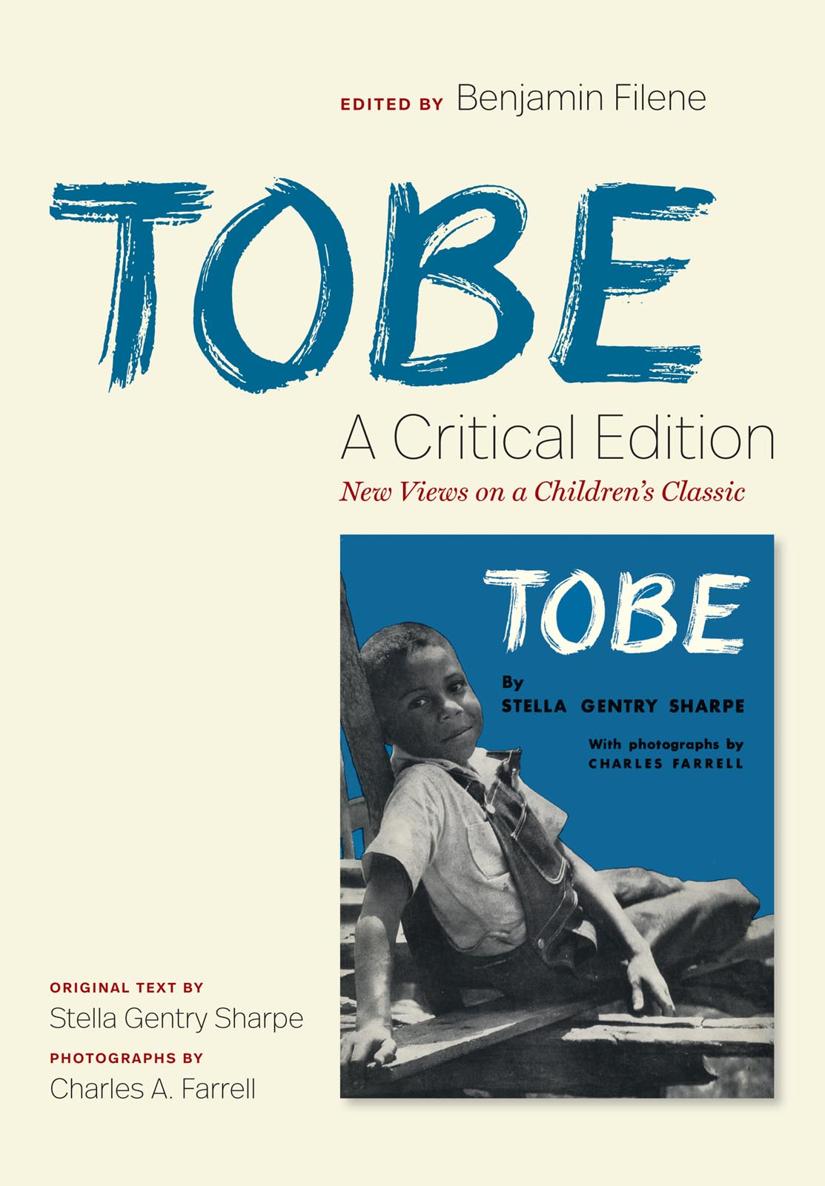

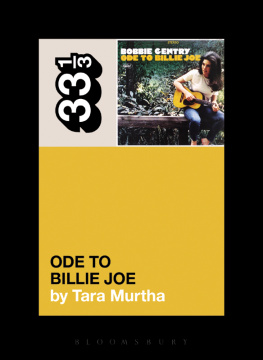

Cover illustration: The cover of the 1939 edition of Tobe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Sharpe, Stella Gentry, author. | Farrell, Charles (Photographer), illustrator. | Filene, Benjamin, editor.

Title: Tobe : a critical edition : new views on a childrens classic / original text by Stella Gentry Sharpe ; photographs by Charles A. Farrell ; edited by Benjamin Filene.

Description: 1. | Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019027163 | ISBN 9781469654164 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469654171 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469654188 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Sharpe, Stella Gentry. Tobe. | Sharpe, Stella GentryCriticism and interpretation. | African American childrenNorth CarolinaJuvenile fiction. | African American farmersNorth CarolinaJuvenile fiction. | African American familiesNorth CarolinaJuvenile fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3537.H31555 T633 2019 | DDC 813/.52dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019027163

A Small Book with Big Reach

Tobe is hopelessly dated; Tobe speaks to our times.

Tobe is progressive; Tobe is retrograde.

Tobe is fiction; Tobe is documentary.

Tobe is not great literature. Well, okay but can it provoke great discussion and reflection?

The reissue of this book, eighty years after its publication, is an opportunity to probe fruitful tensions. In its troubling datedness and troubling timeliness, its progressiveness and its limits, its hokeyness and its humanity, this book speaks to enduring questions about how we see ourselves and each other and the stories we tell to make sense of the uncertain answers.

The deceptive simplicity of the book is what drew me to Tobe and led me on a years-long quest to uncover the story behind the story. My project started not with big themes but with people. I stumbled across Tobe in the archives of the North Carolina Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and immediately I was struck by the photographs. Who were these people? What were they thinking on the day these photos were taken? What did they think of the resulting images (or did they see them?)? How did this moment and this book come about? And what happened next, after the shutter clicks ended?

The dust jacket from the 1939 book offers the first story behind the story. It recounts that in the mid-1930s, an African American boy asked his neighbor, a white schoolteacher, a simple question: Why does no one in my books look like me? She began to wonder the same thing and set out to write a different kind of childrens book: one that featured African American characters in a way that countered the grossly stereotyped depictions in most childrens literature of the time. This would be a dignified, true-to-life story of her young neighbor and his family. It would be Tobes story.

Except the boy who asked the question was not named Tobe. He was Clay McCauley Jr. He lived in rural Orange County, North Carolina. At the time, his father was a tenant farmer, renting land that belonged to Luther Sharpe, the husband of Stella Sharpe, the white schoolteacher. No one knows why she gave Clay the nickname Tobe in the book she wrote about him and his family. But the other names in the bookRaeford, twins Alvis and Alton, William, and Rufusmatch those of Clays siblings. And Sharpe based Tobes story on the life of work and play that she saw the young McCauleys live.

Except that the photographs in Tobe werent taken on the McCauley farm and those arent McCauleys in those pictures. Letters in the archives at the University of North Carolina show that Sharpe did take photos of the McCauley children to illustrate her book, but the story goes that they werent high enough quality to use, and by the time the University of North Carolina Press was ready to go forward with the project, the children were too old: they could no longer play the roles of themselves.

So UNC Press hired a professional photographer, Charles Farrell, and told him to find Tobe. Farrell had taken hundreds of photographs for the Greensboro Daily News and ran a local art shop. For this assignment, he went to an African American neighborhood right down the road, an area called Goshen. He may have known of it because a woman who worked as a domestic in his home went to church there. In any case, Farrell drove up to rural Goshen, just outside the Greensboro city limits and, the story goes, he met a boy. That boy was Charles Winslow Garner; friends knew him as Windy. Farrell had found his Tobe. Over the next several months, Farrell took photos of Windy, his parents, siblings, cousins, and friends: the Garners, Herbins, and Goinses. The photographs richly documented the childrens day-to-day livestheir actual house, school, church. At the same time, staged scenes enabled these real people to stand in for characters in a fictionalized story.

A childrens book might seem an unlikely match for a scholarly publisher like UNC Press, but the time was right for Tobe in several respects. In the 1920s and 30s, the press had published a series of cutting-edge books on African American culture and on the sociology, economics, and culture of race. As the first university press in the South, UNC Press felt it had a special opportunity and obligation to investigate the region. In 1936, it published UNC sociologist Howard W. Odums Southern Regions of the United States, which (across more than 650 pages) set out to definitively depict the forces shaping southern life. Odum saw the South as a laboratory where, through the new tools of social science, scholars could reveal and resolve the issues of the day. There was a belief amongst Southern academics, writes scholar Sharon Suchma, that the North was incapable of speaking about, or resolving, Southern issues. Under the leadership of director William T. Couch, UNC Press aimed to publish leading-edge scholarship and shape popular understandings of the region.

At the same time, Tobe tapped into a broader passion for stories of overlooked or marginalized people. The Great Depression had caused a surge of interest across the country in documenting the power and dignity of the common man and womanfrom Dust Bowl migrants in poignant Life magazine photos and post office murals featuring heroic farmers to a folk music revival in such unlikely places as Washington, D.C., and New York City. Feeling that traditional sources of powergovernment, big business, cultural eliteshad failed them in the economic collapse, many Americans searched for alternative sources of strength: real, seemingly unfiltered stories of ordinary people persevering. While

![Tobe Terrell [Tobe Terrell] - The Gamecaller](/uploads/posts/book/83340/thumbs/tobe-terrell-tobe-terrell-the-gamecaller.jpg)