Jewish Folklore and Anthropology Series

General Editor

Raphael Patai

Advisory Editors

Dan Ben-Amos

University of Pennsylvania

Jane Gerber

City University of New York

Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research

Gedalya Nigal

Bar Ilan University

Aliza Shenhar

University of Haifa

Amnon Shiloah

Hebrew University

Copyright 1993 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48202.

All material in this work, except as identified below, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/.

All material not licensed under a Creative Commons license is all rights reserved. Permission must be obtained from the copyright owner to use this material.

The publication of this volume in a freely accessible digital format has been made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Mellon Foundation through their Humanities Open Book Program.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jewish Moroccan folk narratives from Israel/Haya Bar-Itzhak, Aliza Shenhar: translated by Miriam Widmann in collaboration with the authors].

p. cm. (Jewish folklore and anthropology series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8143-4452-1 (paperback); 978-0-8143-4453-8 (ebook)

1. Folk literature, Judeo-ArabicMoroccoTranslations into English. 2. Folk literature, Judeo-ArabicMoroccoHistory and criticism. 3. TalesMorocco. 4. TalesIsraelShelomi. 5. Legends, Jewish. 6. Jews, MoroccanIsraelShelomiFolklore. 7. Shelomi (Israel)social life and customs. I. Bar-Itshak, Haya. II. Shenhar-Alroy, Aliza. III. Series.

GR98.J49 1993

398.20899276405694dc20 92-44747

Designer: Mary Krzewinski

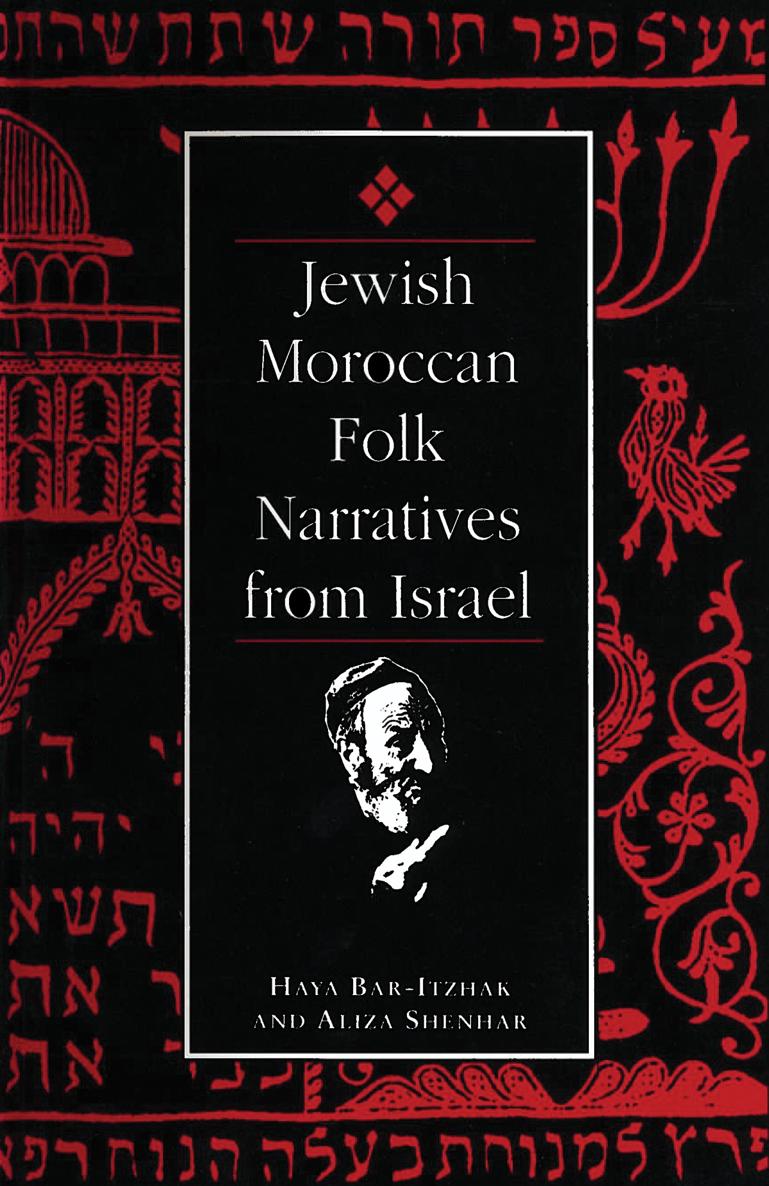

Cover art: Mordekhai Malka (front cover). Parokhet, a curtain for the Holy Ark. Y. Aynhorn collection. Permission of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (background).

Translated by Miriam Widmann in collaboration with the authors.

Wayne State University Press thanks The Israel Museum, Jerusalem for their generous permission to reprint material in this book.

Exhaustive efforts were made to obtain permission for use of material in this text. Any missed permissions resulted from a lack of information about the material, copyright holder, or both. If you are a copyright holder of such material, please contact WSUP at .

http://wsupress.wayne.edu/

Introduction

I n this collection a selection of folk narratives of Moroccan Jews in Israel is presented. The narratives were recorded as part of a research project undertaken in the development town of Shlomi, Israel. An account of the narrators life and a commentary have been appended to each narrative. The narratives were selected to represent proportionally the number of stories told by each story-teller, to present the different genres of the community, and to represent both female and male story-tellers.

The development town of Shlomi is situated in the west region of the Galilee, not far from the Lebanese border. It is located 12 kilometers from Nahariya and 42 kilometers from Haifa. Shlomi was founded in the 1950s to absorb immigrants arriving during the mass immigration after the establishment of the State of Israel. The settlement is named after Shlomi, father of Ahihud head of the biblical tribe of Asher, in whose territory the town of Shlomi was founded. The first inhabitants of Shlomi were Yemenite and Yugoslavian immigrants who lived in the transit camp constructed in the early 1950s. Conditions in those early years were difficult and the settlers moved on to other settlements. They were replaced by immigrants from North Africa. When we did the field work (19811983) most residents, a population of approximately 2,500, were Moroccan Jews, and we recorded the folk narratives from them.

The folk narrative was a feature of Jewish life in Morocco for centuries. Preachers used it when they preached in the synagogue, and narrators used it to teach, educate, and entertain their audiences. The folk narrative had therefore the approval of the bearers of tradition and thousands of listeners for many generations.

Shlomi.

As researchers of folklore we tried, by recording the narratives, to make our contribution to the preservation of the heritage of this ethnic group that at the time was changing fast and might in part no longer be available in a few years. But mainly we wanted to test the folk narrative as a dynamic process. On the one hand, these stories were brought to Israel by the narrators from their country of origin. On the other hand, the narratives were narrated by story-tellers residing in Shlomi who were constantly in contact with the Israeli culture into which they had been transplanted. What happens to traditional folk literature in this process? What impact does the process have on it, and how is it reflected in the narratives themselves? These were central questions we wished to test.

As distinct from the past, the folklore researcher today does not regard himself as a person whose duty it is to salvage the folktale that is sentenced to extinction. We do not doubt that just as Moroccan Jews narrated folk narratives in their country of origin, so is a narrative tradition being generated in Israel. We regard the record we made in Shlomi, the record represented in this volume, as a photograph and documentation of the situation of the folk narrative of Moroccan Jews at a certain crossroads in time and space.

The study focused on two central elements: (a) textual research to examine the aesthetic qualities of the narrative, their division into genres, the various versions and their parallels, and acculturation in Israel; (b) contextual research to examine mainly the performance art of the narrator (intonation, gesticulation, mimics) and the location of the narrative as a communicative process in the narrating society. The collection comprises twenty-one narratives by twelve story-tellers, eleven were narrated by five women story-tellers, and ten were narrated by seven male story-tellers. Each narrative is accompanied by a commentary dealing with aspects we regard as most interesting and relevant, according to the points listed above.

Except for Rabbi Portal, who speaks Hebrew fluently and prefers presenting his narratives in Hebrew even for his family, the story-tellers perform their narratives in the Judeo-Arabic spoken by Moroccan Jews. This special dialect, spoken by this ethnic group, was used in conversing every day and also in composing their creations, both written and oral. The Judeo-Arabic language is interspersed with ancient Hebrew words used by Moroccan Jews, such as the names of holidays and rituals, which were pronounced with a special, typical intonation. We respected and encouraged the decision of the narrators to use their source language because we wanted to record the narratives as they are told in the community, not as told artificially at the request of a researcher. Interaction between the narrator, the audience, and the situation of performance forms the design of the folk narrative text; therefore, we attached the greatest importance to having local narrators addressing a local audience in their habitual language.