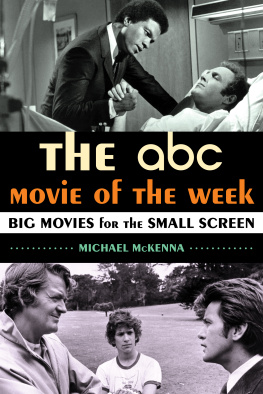

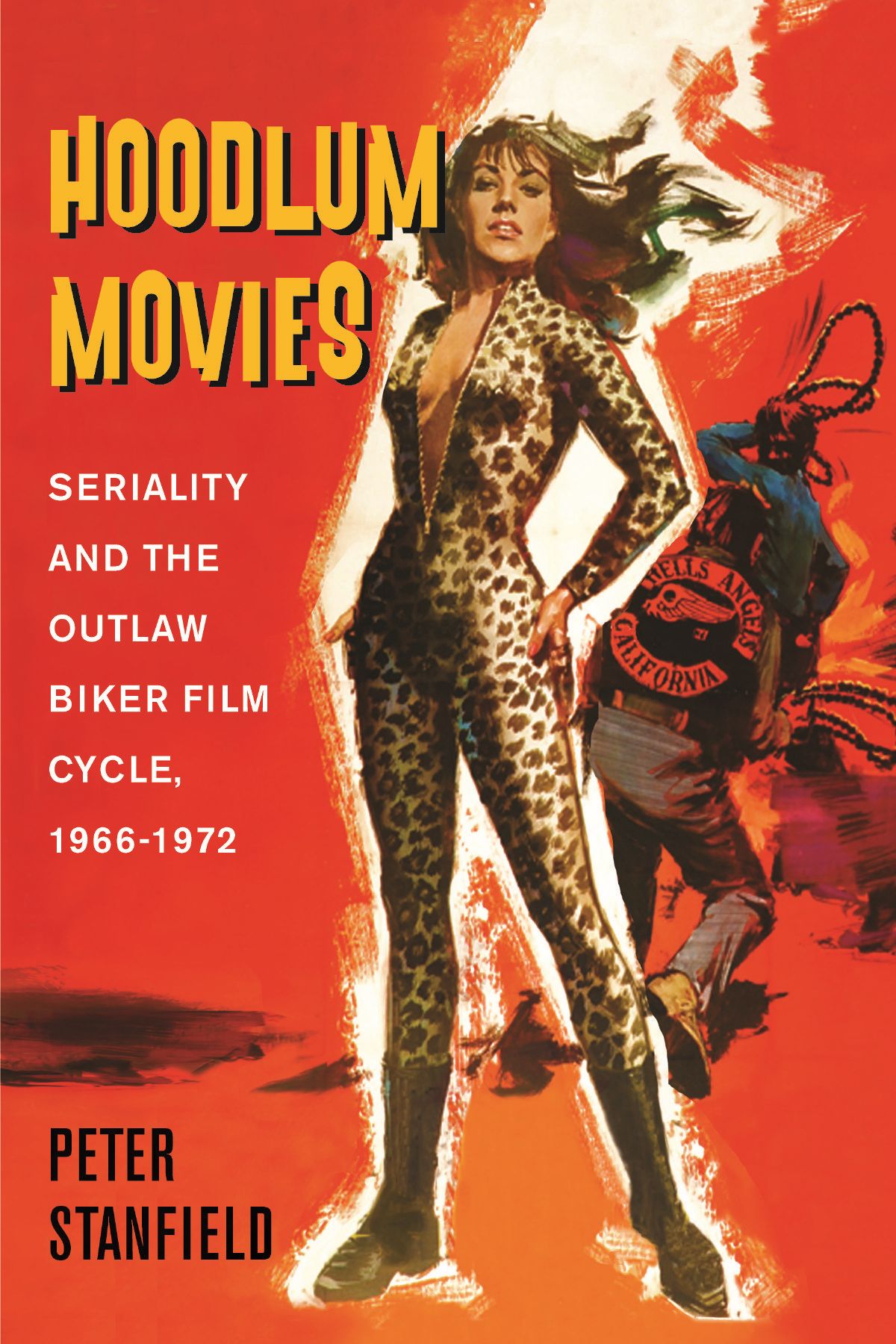

Hoodlum Movies

Also by Peter Stanfield

The Cool and the Crazy: Pop Fifties Cinema

Maximum MoviesPulp Fictions: Film Culture and the Worlds of Samuel Fuller, Mickey Spillane, and Jim Thompson

Body and Soul: Jazz and Blues in American Film, 192763

Horse Opera: The Strange History of the Singing Cowboy

Hollywood, Westerns and the 1930s: The Lost Trail

Edited Collections

Mob Culture: Hidden Histories of the American Gangster Film

Un-American Hollywood: Politics and Film in the Blacklist Era

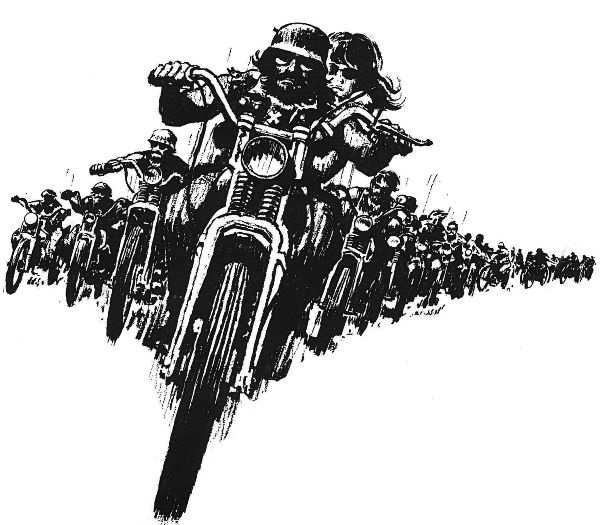

Hoodlum Movies

Seriality and the Outlaw Biker Film Cycle, 19661972

Peter Stanfield

Rutgers University Press

New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, New Jersey, and London

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Stanfield, Peter, 1958 author.

Title: Hoodlum movies : seriality and the outlaw biker film cycle, 19661972 / Peter Stanfield.

Description: New Brunswick : Rutgers University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017053306 | ISBN 9780813599021 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813599014 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Motorcycle filmsHistory and criticism. | Motion pictures20th centuryHistory and criticism.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.M66 S73 2018 | DDC 791.43/655dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017053306

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2018 by Peter Stanfield

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

For Giles but thats the way I like it, baby, Harding

Contents

Hoodlum Gestures

The telephone is ringing

You got me on the run

Im driving in my car now

Anticipating fun

Alice Cooper, Under My Wheels (1971)

As a youth, at the birth of rock n roll music, I was fascinated by custom cars, juvenile delinquency, teenage fashion, post-war hoodlumism (hanging out with motorcycle gangs), beatniks, modern art, drugs and so on, anything of a perverse nature was top priority.

Michael Davis, bass guitarist of Detroits MC5

She may not have shared the same juvenile interests as Michael Davis, yet Joan Didion, the novelist and essayist, was intrigued enough by the specter of postwar hoodlumism to watch nine biker films in seven days before

From The Wild Angels in 1966 until its conclusion in 1972, the cycle of outlaw motorcycle films contained forty-odd formulaic examples. All but one were made by independent companies that specialized in producing exploitation movies for drive-ins, neighborhood theaters, and run-down inner-city movie houses. Despised by critics but welcomed by exhibitors unable to book first-run films, these cheaply and quickly made pictures were produced to appeal to audiences of undereducated mobile youths. Plagiarizing contemporary films for plotlines, the cycle reveled in a brutal and lurid sensationalism drawn from the days headlines and from earlier exploitation fare.

Collectively, these movies portray a picture of America that is the inverse of a progressive, inclusive, and aspirational culture. A nihilistic taint runs through the cycle without providing much in the way of social or aesthetic compensation. Neither on original release nor subsequently have these films accrued cultural capital. In kind, they are stuck with a legacy of negative critical equity. These are dumb, uncouth, loutish films made for real or imagined hoodlums who had no interest in contesting or resisting the entreaties of popular culture. Biker movies are repetitive, formulaic, and fairly indistinguishable from one another. Disreputable and interchangeable these films may be, but their lack of cultural legitimacy and low ambition is a large part of the rationale for this study, inviting questions about seriality and film cycles that are otherwise ignored in histories of 1960s and 70s American film.

Many of the filmmakers involved in outlaw biker moviesJack Nicholson, Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper, and Laszlo Kovacs, among themwould play a significant role in New Hollywood. The biker cycle was not, however, about the new beginnings and open horizons that films such as Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Easy Rider (1969), Five Easy Pieces (1970), The Last Picture Show (1971), and Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) projected. Even as their characters were gunned down or burnt out in the final reel, directors Arthur Penn, Dennis Hopper, Bob Rafelson, Peter Bogdanovich, and Monte Hellman were seen to be laying to rest the monolithic Hollywood studios, with their hidebound practices that produced irrelevant movies with aging starsdramas that were far removed from the interests and concerns of the baby boom generation these cineastes played to.

The biker picture offered an altogether bleaker vision of the state of things in Hollywood; as they trampled over and despoiled past glories, the films in the cycle held out no hope of better days ahead. Like a murder of crows feeding on the carrion of pop culture, the biker film besmirched all that it touched. While Hopper in The Last Movie (1971), Bogdanovich in The Last Picture Show, and Fonda in The Hired Hand (1971) paid homage to the movies made by Howard Hawks, John Ford, and the like, even as they gainsaid the myth of the West, the biker movie merely picked over the genres bones for opportunistic story ideas and stylistic gestures. The grandeur of Fords Monument Valley or the Rocky Mountain locations of Anthony Manns westerns was supplanted in the biker movie by the scrubland surrounding Bakersfield or the dilapidated ranches once used for numerous western film productions and later leased to television companies. A purveyor of national mythologies unequaled in modern popular culture and a cornerstone of American film production that had once accounted for a third of all films produced in Hollywood, as seen through the filter of the biker movie, the western was in a penurious and parlous state. Stripped of its epic stature, the landscape no longer represented the promise of change and renewal. The spectacular deserts of California, Arizona, and Nevada were rendered in the cycle as sprawling junkyards, slag heaps spilling over with the detritus of modern life.

The Spahn Ranch, where once parts of Duel in the Sun were shot and a key location for Bonanza, among the longest running of the western TV series, had become by the late 1960s the setting for underbudgeted biker movies and a playground and hideout for Charles Manson and his murderous family. Once Manson had made the headlines, producers would exploit this connection and thereby enhance the cycles illicit reputation and further sully the image of Hollywood.

If in one sense the cycle is the story of the westerns burial, it is also a tale of the end of the star system, providing the last go-aroundand perhaps last wage checkfor, among others, Gloria Grahame, Jane Russell, Scott Brady, Kent Taylor, and Cameron Mitchell, all of whom looked as if the bottle had taken its toll. Playing alongside these revenants were the progeny of Hollywood, child stars now all grown up, such as Russ Tamblyn and Dean Stockwell, or those who were trading on their parents names: Peter Fonda, Nancy Sinatra, and Jody McCrea, to name but three. The poor production values of the biker film made sure that this juxtaposition of the old and the young did not symbolize a seamless passing of the blessings of one generation to another but instead suggested a lineage now devoid of charisma, talent, or even just a little chutzpah. In the gathering of the generations, family Hollywood had nothing to celebrate.