DIRECTING

FILM

DIRECTING

FILM

FROM PITCH TO PREMIRE

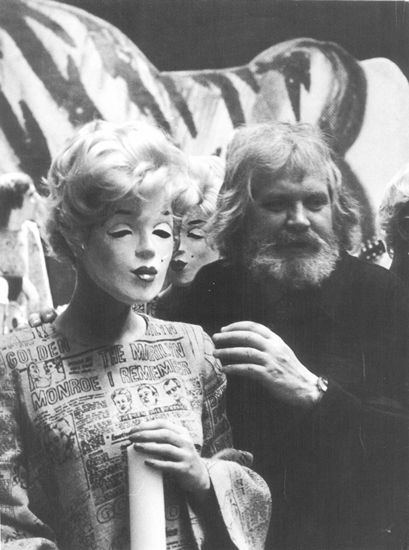

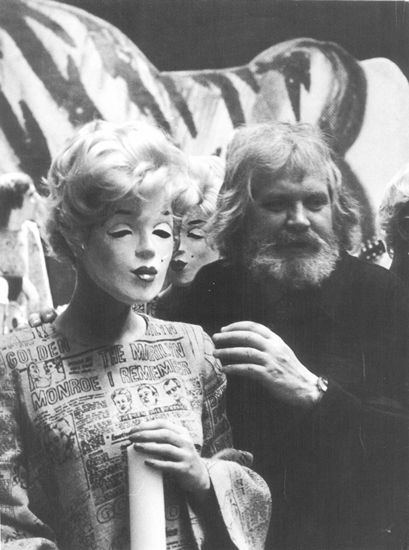

KEN RUSSELL

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

THE PITCH

E veryone who has ever tried to get a film made is a con artist. OK, so sue me! Alright, Ill amend that: everyone who has tried to set up a movie is a liar and a cheat, or at best, a big fat fibber. And thats kosher because everyone in the industry knows that and not only makes allowances, but actually condones it. The one exception is me in my early days, or to be honest, on my very first day. The date was January 3, 1959, with three amateur movies behind me, three children under three and at the ripe old age of 33, I was pitching for my very life a chance to become the greatest director the world has ever known or remain a mediocre photo journalist who was the laughing stock of Fleet Street.

The editor of the photo magazine I freelanced for, had sent me to Spain to get some material on Alexander the Great, starring Richard Burton, which was shooting out of Madrid. Hed also arranged a free trip on SwissAir, providing I took a few publicity stills for them on the way out, with permission to shoot anywhere on the plane. For reasons now forgotten, I flew from Paris Orly at the crack of dawn. Where to start? I loaded my camera and looked around. And there it was a paparazzis dream come true.

Now what would that be today Princess Di as an angel flown down from heaven to give him an exclusive? Or perhaps Charles caught in flagrante in the back of a Land Rover with Camilla Parker Bowles. Yes, it was that big. Well, Im no paparazzi anyway, but it was a very big opportunity to become one, or even start a trend, for I dont think the breed even existed back in 1954. Yes, I had a scoop, an exclusive there wasnt another photographer around for 39,000 feet.

OK, OK, Im coming to it. The hottest scoop in the world at that minute was sitting in Row D, seats 1 and 2 the window and the aisle. They had just secretly married and were on the first day of their secret, secret honeymoon, to a secret, secret destination nobody in the whole, wide world knew about except me. News had got out that very morning that they had just got hitched in Paris and then vanished. It was the hottest story in town, every town it was the romance of the decade, the love story on everyones lips, a fairy tale come true wait for it the marriage of Audrey Hepburn to Mel Ferrar!

Ancient history now, but years ago an earth-shattering event. Trembling and full of trepidation I raised the camera to my eye and focused on the ecstatic lovers with stars in their eyes. I had never seen a happier couple until they caught sight of me. The stars clouded over, I was about to invade their private world and turn their summer into bleak midwinter. I lowered my camera and without as much as glancing in their direction, shamefully returned to my seat.

We arrived in Madrid and I had barely stepped into the glare of the Spanish sun, where there was still not a photographer in sight, before I heard my name being called on the PA system. It was a phone call the editor. He was beside himself with delight.

Get the film to the pilot. Hes doing a quick turn around and flying straight back to Heathrow. Well have it in tomorrows first edition world exclusive. My reply was a verbal suicide note to my career in photojournalism.

Everything now hinged on my interview at the BBC Television Studios at Lime Grove with Huw Wheldon, who in the late 1950s was the editor of the worlds first regular TV arts magazine, Monitor. Now was my big chance to make a fresh start with a career Id always set my heart on ever since the age of nine, when I opened my one and only Christmas present to find a toy projector and a film of Felix the Cat.

age of nine, when I opened my one and only Christmas present to find a toy projector and a film of Felix the Cat.

Monitor had only been running a year. John Schlesinger, the resident documentary filmmaker, was about to leave to make his first feature film. A replacement was needed and Wheldon, who had seen one of my amateur movies and liked it, had granted me an interview. If I could pitch an idea for his programme that appealed to him, Id be home and dry. His first quip, Bit long in the tooth to start a career in film, eh?, hadnt exactly put me at my ease, neither had his hawk-like appearance with beetling brows, beak of a nose and thrusting jaw. Youve seen our programme, I presume, and know our style, so what do you propose? he said.

(Overleaf) Still from Elgar, the BBC drama documentary that started the great Elgar revival. The still shows Elgar riding the Malvern Hills as a boy.

A film on Albert Schweitzer playing Bach to lepers in the jungle, I stammered.

And of all the pitches I have delivered since, and there have been many, none have been more certain of rejection. The hawk glowering at me from behind his massive desk metamorphosed into a thundercloud about to strike me a fatal bolt of lightning. But a split second before it could do so, I started talking fast.

Of course, what Id like to do most of all is make a film on the poet laureate, John Betjeman, reading his London poems in situ. The storms clouds lifted.

A film on Albert Schweitzer playing Bach to Jepers in the jungle, I stammered.

Visions of a film unit flying to darkest Africa, hiring native bearers, trekking through impenetrable jungle to film a doctor with a heavy German accent, playing boring old Bach to an audience who didnt even have the means to applaud, was not then, in 1959, the stuff to win friends and influence viewing figures. And I suspect the same would hold good for today. Just imagine the budget! Whereas dear old John Betjeman was as cuddly as a teddy bear, spoke perfect English though not too posh and could be filmed outside his very own door in Smithfield meat market. No air transport, no native bearers and no big budget.

If you can shoot it in three days, with a crew of three, for 300, youre on, said the Man of Power, now looking as pleased as punch. Seems threes my lucky number. And as things transpired, I continued to pitch ideas to Huw Wheldon at Monitor for many years to come with consummate success. In fact, I can only remember him rejecting one idea in twenty over the next five years. During that time, the boot was often on the other foot as feature film producers started pitching at me.

Such a one was Harry Saltzman; producer of the Bond films, The Battle of Britain, and the Harry Palmer trilogy. He wanted me to make the third and last Harry Palmer. Not because of my succession of acclaimed drama documentary films, such as Elgar, Prokofiev, Bartok and Debussy nd for once the journalist hadnnone of which hed seen. But because Mike Caine, who played Palmer, had seen them and convinced him that my imaginative style of filmmaking would bring a fresh look to the series.

Harry Saltzman, no longer with us, alas, was a grey ball of cosmic energy. Grey suit, grey hair and round as a well, er, ball.

I understand you make art films, he said at our first meeting. I like art, my house is full of it. And Id like to make an art film with you. Anything special you have in mind?

Well Ive always wanted to make a film on Nijinsky, I said.

Not a bad idea, he said, there hasnt been a film with a race horse as the star since National Velvet could be a big money-spinner.

Sorry, Mr Saltzman, I said, I didnt mean the Derby winner, I meant the dancer.

Next page