Copyright 2012 Playboy Enterprises, Inc.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this interview or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For the full Playboy archiveincluding every Playboy Interview ever publishedvisit i.playboy.com .

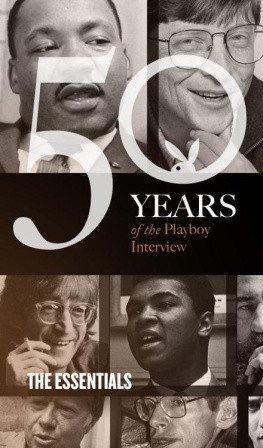

About the Series: In mid-1962, Playboy founder Hugh Hefner was given a partial transcript of an interview with Miles Davis. It covered jazz, of course, but it also included Daviss ruminations on race, politics and culture. Fascinated, Hef sent the writerfuture Pulitzer Prizewinning author Alex Haley, an unknown at the timeback to glean even more opinion and insight from Davis. The resulting exchange, published in the September 1962 issue, became the first official Playboy Interview and kicked off a remarkable run of public inquisition that continues todayand that has featured just about every cultural titan of the last half century.

To celebrate the interviews 50th anniversary, the editors of Playboy have assembled 13 compilations of the magazines most (in)famous interviewsfrom big mouths and wild men to sports gods and literary mavericks. Here is our collection of 12 interviews with the most visionary filmmakers.

Ingmar Bergman, June 1964

In the months since Ingmar Bergmans The Silence world-premiered in Stockholm, moviegoers in a dozen countries have been lining up around the block: some to see the final third of the Swedish film makers celebrated trilogy (following Through a Glass Darkly and Winter Light) on the quest for love as a salvation from emotional death; others to verify the judgment of some critics that this anatomy of lust is the masterwork of Bergmans 20-year career. But most, quite unabashedly, have come to ogle the most explicitly erotic movie scenes on view this side of a stag smokereven after the snipping of more than a minutes film for the toned-down U.S. version. The film has precipitated a rain of abuse on its 45-year-old creatoras a pornographer (by members of the Swedish parliament), purveyor of obscenity (from Lutheran pulpits all over Sweden) and corrupter of youth and decency (via anonymous calls and letters). Outraged at the outcry, Bergman was most offended by the accusation that he filmed the sex scenes merely to shock and titillate his audiences. Im an artist, he told a reporter. Once I had the idea for The Silence in my mind, I had to make itthats all. The son of an Evangelical Lutheran parson who became the chaplain to Swedens royal family, Bergman remembers his years at home with bitterness, as a period of emotional sterility and rigid moral rectitude from which he withdrew into the private world of fantasy. It was on his ninth birthday that he traded a set of tin soldiers for a toy that was to become the catalyst of his creativity: a battered magic lantern. A year later he was building scenery, fashioning marionettes, working all the strings and speaking all the parts in his own puppet theater productions of Strindbergforeshadowing his directorship of a youth-club theater during his years at Stockholm University, where he produced in 1940 an anti-Nazi version of Macbeth which became a minor cause clbreand scandalized his family.

Fired with the zeal of social protest, Bergman quit school the next year, moved into the citys bohemian quarter, began to dress and act accordinglyand to germinate plot lines for satiric and irreverent plays which he never got around to writing. He finally found steady employment as an assistant stage manager, rose swiftly to become a director, and began to earn the reputation for dramatic genius, arrogance and irresistibility to women (hes been married four times) that has become part and parcel of the Bergman legend. Trying his hand at writing a screenplay in 1944, he submitted the manuscript to Svensk Filmindustri, Swedens largest movie company, which decided to film it. Appropriately entitled Torment, it set the tone and theme for a new career, and for the 25 films that followed. In the eight years since his discovery abroad with the international release of The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, Wild Strawberries, The Magician, Brink of Life and The Virgin Spring, he has become the acknowledged guru of the art-film avant-garde, and many critics have joined fellow professionals in hailing him as the worlds first-ranking film maker.

An exacting taskmaster, he does not brook the slightest deviation from the script in the course of shooting, nor countenance the presence of outsiders anywhere in the studioespecially journalists, of whom he has never been fond, on or off the set.

It was with some trepidation, therefore, that we approached the mercurial moviemaker with our request for an exclusive interview. But he replied with a cordial invitation to visit him in Stockholmwhich we accepted, arriving late last February, in the middle of the somber Nordic winter, for a week-long stay.

Our conversations took place in his small, sparsely furnished office backstage at the Royal Dramatic Theater in downtown Stockholm, where, as the newly appointed manager of the national theater, he was devoting his directorial energies full time, on an extended sabbatical from film making, to staging the works of such theatrical iconoclasts as Brecht, Albee and Ionesco. Meeting with us for an hour or so each morning (when Im most alive, he told us), he would arrive promptly at nine, dressed always, indoors and out, in heavy flannel slacks, polo shirt, wool cap and a tan windbreaker with a dry cleaners tag still stapled to a cuff. Our interview began with a wry smile from our subjectand a disarming greeting in which he reversed roles by asking the first question.

Bergman: Well, are you depressed yet?

Playboy: Should we be?

Bergman: Perhaps you havent been here long enough. But the depression will come. I dont know why anybody lives in Stockholm, so far away from everything. When you fly up here from the south, its very odd. First there are houses and towns and villages; but farther on there are just woods and forests and more woods and a lake, perhaps, and then still more woods with, just once in a while, a long way off, a house. And then, suddenly, Stockholm. Its perverse to have a city way up here. And so here we sit, feeling lonely. Were such a huge country; yet we are so few, so thinly scattered across it. The people here spend their lives isolated on their farmsand isolated from one another in their homes. Its terribly difficult for them, even when they come to the cities and live close to other people; its no help, really. They dont know how to get in touch, to communicate. They stay shut off. And our winters dont help.

Playboy: How do you mean?

Bergman: Well, we have light in the winter only from maybe eight-thirty in the morning till two-thirty in the afternoon. Up north, just a few hours from here, they have darkness all day long. No daylight at all. I hate the winter. I hate Stockholm in the winter. When I wake up during the winterI always get up at six, ever since I was a childI look at the wall opposite my window. November, December, there is no light at all. Then, in January, comes a tiny thread of light. Every morning I watch that line of light getting a little bigger. This is what sustains me through the black and terrible winter: seeing that line of light growing as we get closer to spring.

Playboy: If thats how you feel, why not leave Stockholm during the winter and work in the warmer climates of such film capitals as Rome or Hollywood?

Bergman: New cities arouse too many sensations in me. They give me too many impressions to experience at the same time; they all crowd in on me. Being in a new city overwhelms me, unsettles me.

Playboy: Thereve been reports that you feel what youve called the great fear whenever you leave Sweden. Is that why youve never made a film outside the country?