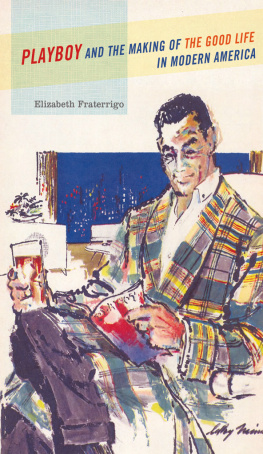

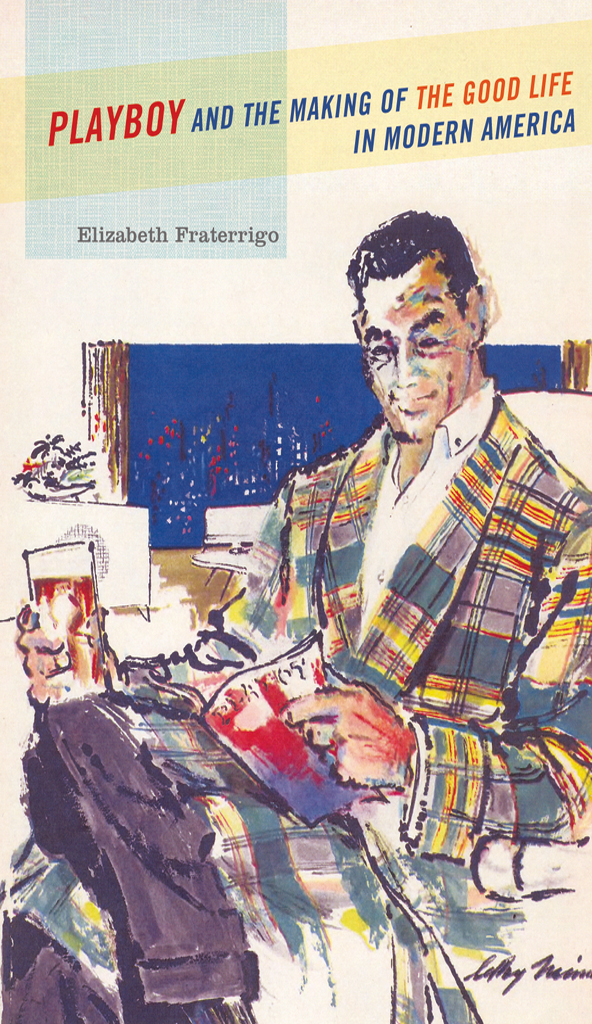

Playboy and the Making of the Good Life in Modern America

PLAYBOY

and the MAKING of the GOOD LIFE in MODERN AMERICA

Elizabeth Fraterrigo

2009

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Copyright 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc.

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fraterrigo, Elizabeth.

Playboy and the making of the good life in modern America / Elizabeth Fraterrigo.

p.cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-19-538610-3

1.Playboy Enterprises.2.Playboy (Chicago, Ill.)3.United StatesSocial conditions19454.United StatesMoral conditions20th century.5.Social changeUnited StatesHistory20th century.6.Arts and societyUnited StatesHistory20th century.7.LiberalismSocial aspectsUnited StatesHistory20th century.I.Title.

PN4900.P5F73 2009

051dc222009011643

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Many individuals and institutions have provided generous assistance for this book and I am pleased to have the opportunity to express my gratitude to them in these pages. I would like to thank the librarians and archivists of the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University; the Chicago History Museum; the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction, Inc.; Lied Library at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas; the E.M. Cudahy Memorial Library of Loyola University Chicago, and the Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. I am also grateful for the help of several people at Playboy Enterprises, especially Lee Froelich, who facilitated access to company archives in Chicago, and Steve Martinez, who helped me navigate collections at the Playboy Mansion in Los Angeles. Marcia Terrones oversaw requests for permission to reproduce material from the magazine. Jill Boysen deserves many thanks for her patience and diligence in tracking down images for the book. Special thanks go to Leroy Neiman, whose work At Ease graces the dust jacket. Lastly, I thank Hugh Hefner for allowing me to peruse his personal scrapbooks and for graciously agreeing to be interviewed for this book.

At several stages of research and writing, I was fortunate to have received financial support from the following sources, for which I am grateful: the Arthur J. Schmitt Dissertation Fellowship and the DePersis-Urbanek Fellowship in Womens History from Loyola University Chicago; the Carter Manny Dissertation Award from the Graham Foundation; a Summer Fellowship from the College of Liberal Arts at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas; and funding from the history department at UNLV for travel to collections. I also wish to thank Ed Shoben, former dean of the College of Liberal Arts at UNLV, and Eugene Moehring, former history department chair, for granting a course reduction during the 200607 academic year that provided much-needed time to work on the book.

During its earlier life as a dissertation, this project benefited from the wisdom and support of many people. Susan Hirschs graduate course on womens and gender history inspired my initial thinking about the history of masculinity and bachelorhood. Patricia Mooney-Melvin never let me forget that careful thinking and clear prose go hand in hand. Where I approach clarity in these pages, she deserves much credit. By chance, Lew Erenberg had a box of old Playboys in his office at a crucial moment when I was casting about for a topic in his graduate seminar, and I learned from him the value of thinking critically about popular culture as a meaningful site of expression. I am grateful not only for his guidance of the dissertation that grew out of that seminar, but also for his encouragement and advice as I transformed the dissertation into this book. I also wish to thank my fellow history graduate students as well as the members of the Womens Studies Graduate Scholars Program at Loyola University Chicago, who provided intellectual companionship as this project first took shape and helped make graduate school a fulfilling experience. The Newberry Library Urban History Dissertation Group provided helpful feedback as well as a forum for intellectual engagement while I was writing.

Las Vegas has served as a fascinating setting in which to ponder capitalism, consumption, sexuality, and self-indulgencethemes that suffuse this bookand for many years, the history department at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, provided a welcome and rewarding environment in which to do so. Faculty, staff, and students in the history department supported this project in various ways. I am thankful to many for reading and commenting on material or for offering helpful advice, especially Gene Moehring, David Wrobel, Mary Palevsky, David Holland, Yuma Totani, and Marcia Gallo. My late colleague, Willard Rollings, and his wife, the late Barbara Williams-Rollings, saved me many trips to special collections by providing me with a cache of Playboys after I remarked that it would be helpful to have the magazine on-hand as I worked on the book. Joanne Goodwin, Andy Kirk, Greg Brown, Kevin Dawson, Kathy Adkins, and Lynette Webber offered encouragement and shared my enthusiasm for this project over the years. Stimulating discussions with students in my fall 2007 colloquium on gender history and in my fall 2008 course on American popular culture energized me as I reworked parts of the manuscript. Leisl Carr Childers cheerfully carved time from a busy schedule to read page proofs. Michelle Lettieri coaxed me away from the computer for much-needed and rejuvenating breaks. Special thanks go to my friends and colleagues Michelle Tusan and Elizabeth White Nelson. Michelle Tusan gave helpful feedback on portions of the manuscript, along with constant encouragement and sage advice that kept me on track. Elizabeth White Nelson read multiple drafts, asked probing questions, and offered thoughtful comments that vastly improved this work. I owe her a special debt for her unflagging interest in this project, even when my own energy was waning, and for making her constructive criticism all the more palatable by dispensing it along with delicious and memorable meals.

I am also enormously grateful for the insightful comments and suggestions from the readers for Oxford University Press, which enriched and helped shape this book. At OUP, Susan Ferber has been a patient guide through every stage of the publishing process and her skillful editing has much improved the manuscript. Jessica Ryan deserves thanks for shepherding the book through the production process and Stacey Hamilton for her careful copyediting.