Foreword

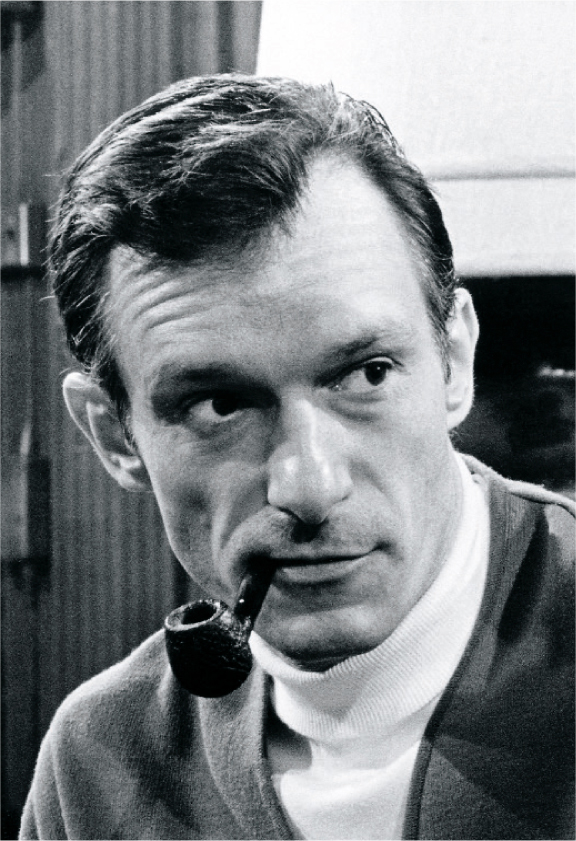

By Hugh M. Hefner

Hugh Hefner, by Alexis Urba, 1966

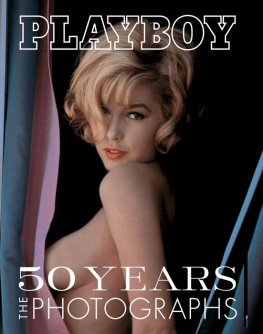

Fifty years after the first Playboy Club opened and the first Bunny performed her elegant dip to serve a keyholder the beverage of his choice, you hold in your hand a tribute to two American icons.

To create an icon requires a chemistry, a joyful collaboration between artist and audience. In 1960 Playboy magazine reached a million readers a month. American males were familiar with the lifestyle celebrated in the magazine. They reveled in the fantasy, the combination of impeccable style, taste, humor, and qualitythe essentials of what was known as the good life. They were hungry for something more. I wanted to make the fantasy real, to give the world of Playboy a street address.

Historians have looked at the early success of Playboy and suggested I had tapped into the male zeitgeist. Postwar American males were free agents, restless, not willing to be tied down to the model of family togetherness espoused by magazines like McCalls . Men carried that energy into the urban night, listening to jazz in smoky clubs, enjoying the revolutionary humor of a new brand of comedian. The magazine re-created that heady mix for the newsstand and coffee table. I drew on my own passions and roots in Chicago nightlife. I had a template in mind. One of my favorite clubs, the Gaslight, had been exclusive. Members were keyholders, and the staff was dressed in costumes of the Gay Nineties. You may never have heard of the Gaslightit failed to achieve iconic status. But the Playboy Clubs enjoyed a different fate. The formula was not different from the speakeasies of the Roaring Twenties or the legendary sporting houses in New Orleans Storyville. We presented an intoxicating mix of food and alcohol, music and entertainment in a sophisticated, sexually charged atmosphere of a more contemporary nature.

Marshall McLuhan once described how television had created an urge for involvement, a yearning to complete the picture. He called this new force of nature the participation mystique. To participate in Beatlemania, he said, one had only to grow ones hair. To participate in the Playboy mystique, one had only to be a keyholder.

To achieve icon status requires accomplices. Variety called the Playboy Club in Chicago a Disneyland for adults. Within two years 300,000 keyholders belonged to our version of the magic kingdom. Just as the magazine was a Rorschach test for America, so too were the clubs. Because club members werent allowed to touch the Bunnies, Time complained that the clubs were brothels without a second story. The clubs became a topic for serious writers. In 1963 Norman Mailer described the sceneand above all else, the clubs were just that, a scenein The Presidential Papers: The Bunnies went by in their costumes, electric blue silk, kelly green, flame pink, pin-ups from a magazine, faces painted into sweetmeats, flower tops, tame lynx, piggie, poodle, a queen or two from a beauty contest. They wore Gay Nineties rig that exaggerated their hips, bound their waists in a ceinture and lifted them into a phallic brassiereeach breast looked like the big bullet on the front bumper of a Cadillac. Long black stockingsup almost to the waist on each sideand to the back, on the curve of the can, as if ejected tenderly from the body, was the puff of chastity, a little white ball of a Bunnys tail that bobbled as they walked. The Playboy Club was the place for magic.

It was just that. Mailer was not the only reporter to take notes. Gloria Steinem went undercover as a Bunny in the New York club, and before letting her agenda warp her journalism, was honest enough to report her first impression: The total effect is cheerful and startling. The story launched her career.

We knew the clubs had attained cultural liftoff when James BondIan Flemings own iconic creationflashed a Playboy key in Diamonds Are Forever. Of course the male sex symbol of the century would be a member. And, in real life, celebrities like John Lennon and Bob Dylan chilled in the clubs (or as they said back in the day made the scene).

Often overlooked was the quiet revolution. In the magazine, the clubs, and the television show, I presented a world that reflected my own values. The clubs were interracial. We launched the careers of black comedians who had never worked in white establishments. It took the rest of the decade for America to catch up.

The heart of the club experience was the Bunny. I spent my childhood at the movie palaces of Chicago. My dreams were Hollywood dreams. I was mesmerized by a film about the great showman Florenz Ziegfeld, the great impresario of the Twenties. He created one of the first sex symbols of the century, the Ziegfeld Girl. I envisioned the Bunny as a waitress elevated to the level of a Ziegfeld Follies Girl. I had already created one sex symbolthe Playmate. I wanted to try for a second.

As you will discover in the following pages, it was terrific fun. I personally designed the outfitthe cuffs, the collar, the cottontailbut the women who filled the costume deserve the credit. Women like Lauren Hutton, Debbie Harry, and Kathryn Leigh Scott, author of The Bunny Years . Gloria Steinem, at the end of her piece, concluded that All Women are Bunnies. But she was wrong. It took a special type of independent spirit. One that comes alive on these pages.

The Bunny became an American classic, instantly recognizable, a shorthand for sexy, liberated, independent. A pre-feminist feminist. College coeds donned the attire for parties. The design was patented and put on display in the Smithsonian.

Fifty years is a long time. We packed the house on a frigid opening night in 1960, and we continue to pack the house in 2010 at the Palms in Las Vegas. This book is a celebration of half a century of Playboy Club and Bunny culture. A celebration of a certain mystique.

Introduction

By John Dante

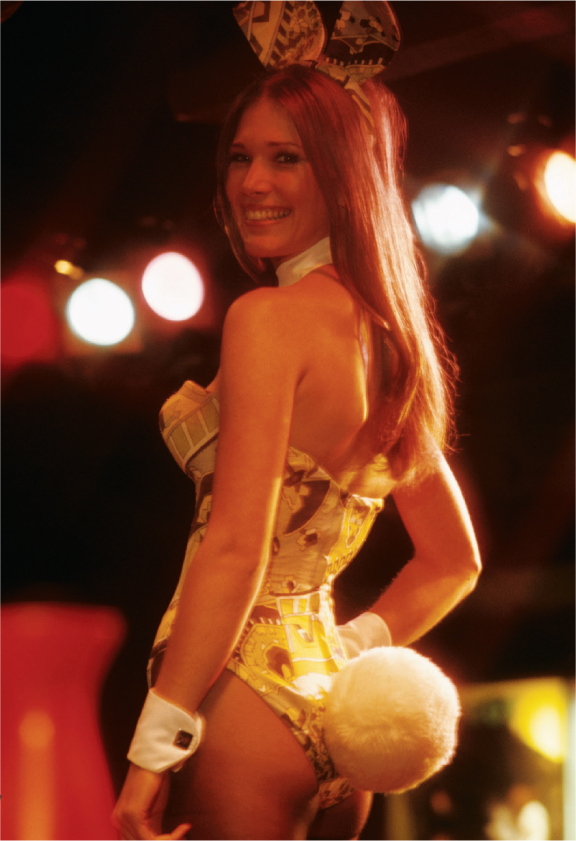

Judy Juterbock, New York

I started working for the Playboy Club of Chicago as a bartender in December 1960, and sometime in 1961 I was promoted to room manager. It was a great job. It wasnt really workif they had asked me to do it for nothing, I would have. Gladly. I was in my early 30s, and working for Playboy was like going to a great party every night.

If I close my eyes and concentrate, I can see myself in the After Six tuxedo, working my way through the always-crowded Living Room. Harold Harris and his trio livened up the room with a stream of marvelous jazz at the popular piano bar. The music and the tinkle of ice cubes in highball glasses, and the laughing and high-spirited chatter of the male members (at that time only men could be members) and their female companions, set a tone of excitement that went full blast and unabated till we, good-naturedly, pushed out the last tipsy customer at four oclock in the morning. Nobody ever wanted to leave the place.

Along the back wall of the Living Room there was arrayed as fine a buffet as could be found in any expensive restaurant in town. There were Southern-fried chicken, hickory-smoked baby-back ribs with a tangy barbeque sauce, and shish kebabs made with chunks of prime beef that were broiled and skewered on foot-long spits. And there was always crisp, hot pizza.