This book was published with the assistance of the Fred W. Morrison Fund of the University of North Carolina Press.

2021 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Designed by Jamison Cockerham

Set in Arno, Scala Sans, Cutright, Irby, and Isherwood by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

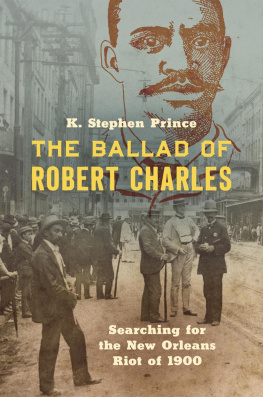

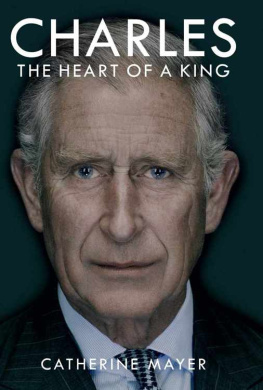

Cover illustrations: (top) Sketch of Robert Charles from the Daily Picayune (New Orleans), July 25, 1900, 8; (bottom) Citizen policemen in New Orleans; photograph courtesy of the Collections of the Louisiana State Museum, New Orleans

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Prince, K. Stephen, author.

Title: The ballad of Robert Charles : searching for the New Orleans riot of 1900 / K. Stephen Prince.

Description: Chapel Hill : The University of North Carolina Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020038263 | ISBN 9781469661810 (cloth) | ISBN 9781469661827 (paperback) | ISBN 9781469661834 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Charles, Robert, 1865?1900. | Race riotsLouisianaNew OrleansHistory19th century. | New Orleans (La.)Race relations. | New Orleans (La.)Historiography.

Classification: LCC F379.N553 C426 2021 | DDC 976.3/3506092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020038263

A version of originally appeared as K. Stephen Prince, Remembering Robert Charles: Violence and Memory in Jim Crow New Orleans, Journal of Southern History 83, no. 2 (May 2017): 297328.

INTRODUCTION

A Song Forgotten

This book tells the story of an event too explosive to remember, a song too dangerous to sing. In 1938, folklorist Alan Lomax recorded a series of interviews with pioneering jazz pianist and New Orleans native Jelly Roll Morton. During their conversations, Morton expounded, exaggerated, and waxed philosophical, living up to his reputation as a legendary teller of tales. However, his treatment of one topicthe 1900 New Orleans riotwas notable less for what Morton said than for what he left unsaid. Morton was a young child in July 1900, when a black man named Robert Charles killed several white police officers, sparking a week of racial violence that claimed the lives of more than a dozen black and white New Orleanians. Thirty-eight years later, as Morton sat with Lomax, playing a droning tune on the piano, he shared his version of the Robert Charles story. Partway through his tale, he paused and said something surprising: Like many other bad men, Morton said, Robert Charles had a song originated on him. This song was squashed very easily by the [police] department, and not only by the department but by anyone else who heard it, due to the fact that it was a trouble breeder. So that song never did get very far. He continued: I once knew the Robert Charles song, but I found it was best for me to forget it and that I did in order to go along with the world on the peaceful side. Perhaps Jelly Roll Morton had truly forgotten The Ballad of Robert Charles by the time of the interview with Lomax. Perhaps he simply chose not to share it. Perhaps it had never existed at all. Regardless, Jelly Roll Mortons tantalizing accountof the song that he would not remember but could not forgetinvites us to dig deeper, following the tangled threads of race, power, violence, and memory woven through the story of Robert Charles and the 1900 New Orleans riot.

At around 11 P.M. on Monday, July 23, 1900, Robert Charles and a friend named Leonard Pierce sat on a stoop at 2815 Dryades Street, in an uptown area of New Orleans today known as Central City. Three members of the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) approached. When Robert Charles tried to stand up, patrolman August Mora moved to strike him with his baton. After a brief struggle, Mora and Charles drew their weapons and exchanged fire. Both men were wounded, and Charles fled into the night. Several hours later, police tracked Charles to his rented room nearby. As the officers approached his door, Charles opened fire with a Winchester rifle, killing Capt. John T. Day and patrolman Peter J. Lamb. Before the police could regroup, Charles escaped once more.

With Charles in hiding, white residents of New Orleans turned on innocent African Americans. Tensions simmered on July 24, but large-scale violence did not break out. However, the next night, Wednesday, July 25, a white mob gathered and began to target black residents. After they were denied entry to the Parish Prison, where Leonard Pierce was being held, the mob spent the rest of the night roaming the city streets in search of victims. Three African Americans were killed or mortally wounded on the first night of rioting. Many more were injured. Through it all, the NOPD did little to protect the citys black population. On the morning of Thursday, July 26, Mayor Paul Capdevielle deputized an emergency civilian police force in the hopes of suppressing the rioters. Some semblance of order returned to the citys streets by early evening. However, several more acts of violenceincluding the shooting of a black woman in her own homeoccurred overnight.

On Friday, July 27, the New Orleans Police Department finally located Robert Charles. On the basis of an anonymous tip, Sgt. Gabriel Porteous and Cpl. John F. Lally went to investigate the residence of Silas and Martha Jackson, at 1208 Saratoga Street. When they entered a small outbuilding in the backyard, Charles burst from his hiding place. He shot the two officers, killing Porteous and mortally wounding Lally. He then retreated to the second floor of the building. As word of the shootings spread, a heavily armed crowd gathered near the corner of Saratoga and Clio Streets. Over the next several hours, hundreds of weapons fired thousands of rounds at the small structure where Charles made his last stand. During the shootout, Robert Charles killed three members of the crowd and wounded several more. Desperate city authorities finally approved a plan to set fire to Charless hideout. He was shot and killed as he emerged from the burning building. The enraged crowd set upon the corpse, beating it and shooting it more than thirty times.

During the final shootout, members of the Saratoga Street crowd murdered an unidentified black man who was in police custody. Around the same time, a white mob killed an African American man near the French Market. Later that night, in one final act of racial vengeance, a white crowd set fire to the Thomy Lafon School, the citys finest black educational institution.

During the last week of his life, Robert Charles killed seven white people, including four members of the New Orleans Police Department. According to the official tallies published in the citys newspapers, white mobs murdered six African Americansnone of whom had anything to do with Charlesand wounded many more. It is entirely possible that there were additional black fatalities, but incomplete police and hospital records make it impossible to know for certain.