The Field

Researchers

Handbook

Related Titles from Georgetown University Press

Career Diplomacy: Life and Work in the US Foreign Service, Second Edition

BY HARRY W. KOPP AND CHARLES K. GILLESPIE

Careers in International Affairs: Ninth Edition

EDITED BY LAURA E. CRESSEY, BARRETT J. HELMER, AND JENNIFER E. STEFFENSEN

Working World: Careers in International Education, Exchange, and Development, Second Edition

BY SHERRY LEE MUELLER AND MARK OVERMANN

The Field

Researchers

Handbook

A Guide to the Art and Science of Professional Fieldwork

DAVID J. DANELO

2017 Georgetown University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Danelo, David J., author.

Title: The field researchers handbook : a guide to the art and science of professional fieldwork / by David J. Danelo.

Description: Washington D.C. : Georgetown University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016033267 (print) | LCCN 2016040148 (ebook) | ISBN 9781626164376 (pb : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781626164451 (hc : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781626164383 (eb)

Subjects: LCSH: Social sciencesFieldwork. | Social sciencesResearch. | AnthropologyFieldwork. | ResearchHandbooks, manuals, etc. | ResearchMethodology.

Classification: LCC H62 .D226 2017 (print) | LCC H62 (ebook) | DDC 300.72/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016033267

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

18 17 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 First printing

Printed in the United States of America

Cover design by Faceout Studio, Charles Brock. Cover image by Thinkstock.

for Dana and Sina

Contents

Introduction

What Is Field Research?

Have you ever traveled for the specific purpose of learning something? Taken a pilgrimage to an ancestral homeland to understand your family heritage? Gone out to a job site to find the facts from the factory instead of the conference room? Stood on a street corner and halted pedestrians to ask survey questions? Interviewed a colleague to learn a different linguistic and cultural approach to a puzzling problem? Crossed an ocean for work, study, or personal exploration?

That is field research.

Wait. Hang on a minute. Is that really all there is to it? Doesnt field research require conformity to scientific methods? Can you really call yourself a researcher if an Institutional Review Board, senior officer, program supervisor, or dissertation committee chair hasnt signed off on a proposal? Dont you have to be certified by a guild or government agency to be able to claim the title of field researcher?

Not at all.

Scientists, anthropologists, and sociologists define field research as the collection of information outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. Volumes of methodological texts weigh in with competing theories on how to process statistics and surveys, the types and styles of data collection, and reminders to keep reflexivity and positionality in mind when conducting qualitative analysis. There is a conventionespecially in academic circlesto understanding the processes and particulars of what comprises field research.

But Im not here to talk about how to understand, explain, or theorize field research. This book is about how to do it. Regardless of whether the context is policy analysis, data gathering, or professional investigation, fieldwork requires the ability to find relevant facts and the capacity to evaluate personal risk. In academic studies, corporate finance analyses, public policy assessments, and private client reports, researching away from home includes cultural observations, expert interviews, and data collection to analyze information and determine options.

Is there anything that can prepare us for this experience other than just doing it?

Yes, I think so.

I say this because Ive spent the past decade of my professional life as a field researcher. Initially, I didnt know how to describe what I was doing. My first ten years beyond high school were spent in the US military, first as a Naval Academy midshipman and then a Marine Corps infantry officer. In the summer of 2004, during a combat tour in Iraq, I decided if I made it back home in one piece, I wanted to get paid to travel and write for the rest of my life. I thought the only people who fit that job description were called foreign correspondents, and I spent the first three years of my postmilitary career striving to become one.

My assumption was wrong. Many professionals get paid to travel and write, and few of them, particularly in the twenty-first century, seem to be journalists. Thanks to Facebook, Twitter, and Google Translate, the market for foreign correspondents has never been lower. International bureau chiefs are still around, but news services rely more on local aggregated content from worldwide social media than on hired staff to identify and distribute major events in real time. The few foreign correspondents left are working twice as hard to find stories and get field time. With the internet driving international news cycles, the luster and mystique associated with the title, even for the largest media organizations, will never be what it once was.

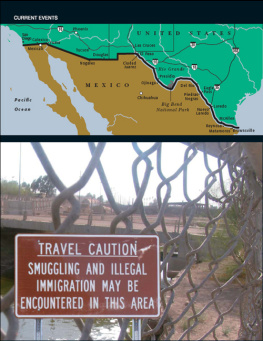

Despite those limitations, I spent two years as a freelance writer, dispatching stories from both foreign and domestic locales. In 2007, I traversed the entire length of the US-Mexico border for the better part of three months, a journey that framed the substance of my second book. As interviews and observations yielded new and unexpected discoveries, I sensed that my field research on the US-Mexico border enabled me to better understand borders in general. I didnt know what it meant, but it suggested I might have a future in research beyond journalistic curiosity.

When The Border was published in the fall of 2008, drug violence seemed to be gripping northern Mexico and financial calamity had stricken global markets. The book didnt sell many copies, butto my surpriseI had suddenly been branded as a border expert. A colleague at the US State Department asked me to join a small team of specialists from different fields who assessed security and international border conditions worldwide through interviews and field observation, delivering their written reports within two weeks of returning.

In keeping with my original ambitions, I spent the next two years being paid to travel and write. But unlike in journalism, my data collection and published work were exclusively for private clients. At that time, many were affiliated with the United States government, but a handful of academic and corporate organizations were also interested in my research. Most reports I wrote were labeled for official use only, as were the interviews or debriefing sessions I participated in following international travel. As I meandered around the world, I met hundreds of other people who were traveling and writing their own nonpublic reports, most often for universities, governments, nonprofits, or multinational corporations. I learned that many more field researchers get paid to travel and write than foreign correspondents.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.