Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2008 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in

any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying

and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the

prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Resina, Joan Ramon.

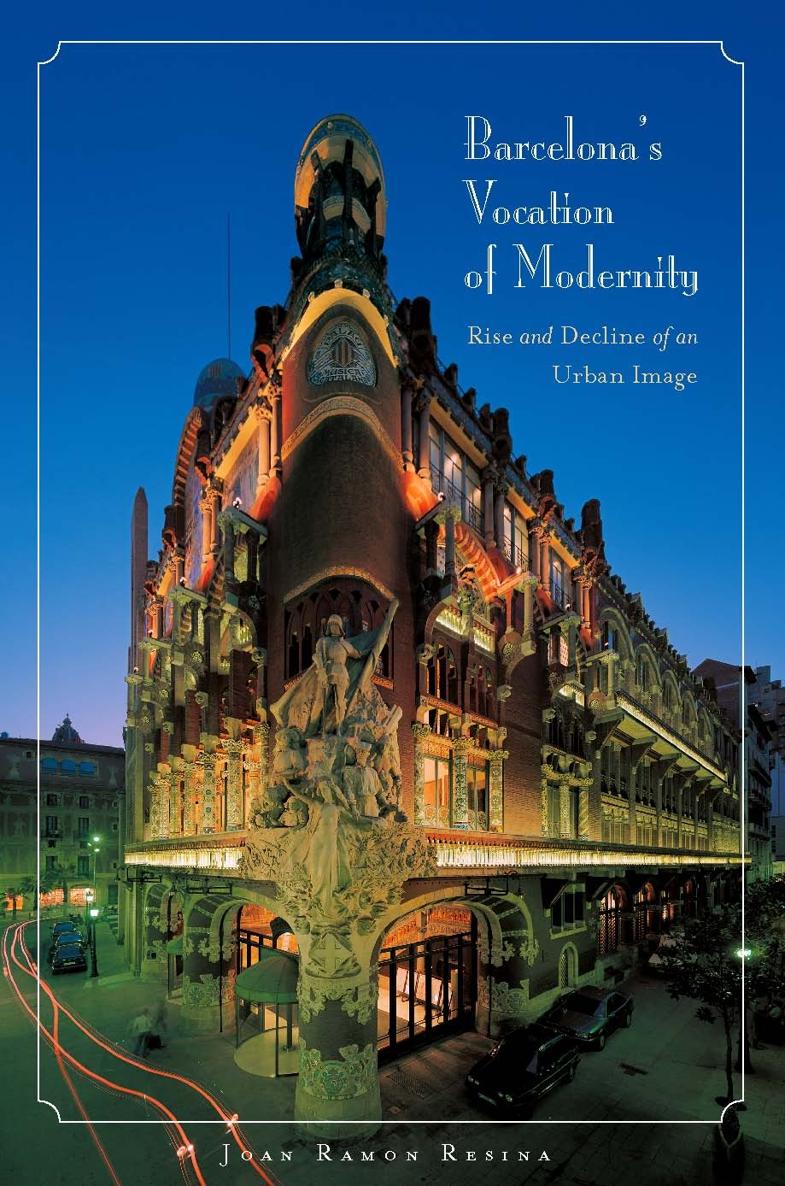

Barcelonas vocation of modernity : rise and decline of an urban image / Joan

Ramon Resina.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

9780804787505

1. Barcelona (Spain)Social life and customs. 2. Sociology, UrbanSpain

Barcelona. I. Title.

DP402.B265R46 2008

307.76094672dc22

2007035632

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10/12 Sabon

This book was published with the assistance of Stanford Universitys School of

Humanities and Sciences and the Program for Cultural Cooperation between

Spains Ministry of Culture and United States Universities.

Acknowledgments

A fragment of Chapter 5 was published independently in Modern Language Review , and large tracts of Chapter 6 appeared in PMLA . I thank the editors of both journals for permission to use those materials. I am indebted to the following persons and institutions for permission to reproduce some of the images in the book: Arxiu Histric and Arxiu Fotogrfic de lArxiu Histric de la Ciutat de Barcelona, Arxiu Municipal de Grcia, Famlia Casas i Galobardes, Fundaci Forum Universal de les Cultures, Junta del Temple de la Sagrada Famlia, Xavier Bertral, Ricardo Bofill, Xavier Castell, and Sofia Picaol. I am especially grateful to Jordi Falgs, Alonso Carnicer, and Andreu Villa for their assistance in securing some of the images; to Sepp Gumbrecht for believing in this book; to Roland Greene for divisional support toward the publication; and to Norris Pope, of Stanford University Press, for betting on a project somewhat eccentric to the presss axial concerns. Thanks are also due to the students who over the years have taken my seminars on Barcelona, and to those very special people who, being closest to me in every sense of the word, have borne the hidden costs of a long-term endeavor.

INTRODUCTION

The City as Social Form

The city is the way we moderns live and act, as much as where.

James Donald

That the city is a social form is a banal observation. But trivial truths sometimes contain the crux of a problem. Let us put pressure on the words social and form . They are not incompatible, but they do not entail one another either. Form belongs in the realm of aesthetics, that is, the domain of sensible perception, Aristotles ton aistheton eidon ( On the Soul 424a), but also in the realm of intelligibility through a complex form of recollection, the dialectic, which for Socrates was actualized in responsible exercise of citizenship. By social we understand the nature and quality of the collective space that results from arrangement of human relations according to certain political norms and ideas, whose first visible expression the city is.

What is the city if not an idea supported by temporal and spatial paradigms? There is no idealism in this assertion. Everything human that exists in space and in time, everything local , and thus real in an empirical sense, is bound up with the evolution of historical problems for which the city is at once the visible formulation and the attempt to resolve them. This evolution is subject to contingency, but it takes place under the aegis of models, which are at once moral and belief systems. Such models contribute powerfully to the forms of settlement but also to the sorts of experience the city promotes or deflects. This is to say that, as social form the city fulfills a symbolic function. Which is still a fairly banal observation. But it also means (and this may be less intuitive) that as social form the city hinges on all systems of signification, thus providing not only a synthetic feel for the individuals participation in those systems but more important a useful frame to study specific developments in one or the other such system. The city is thus the sum of all relations among its inhabitants as well as between them and outsiders, people immersed in other systems. It is important to note that these relations are not only synchronic but historical as well. They include the elements of tradition and memory, which determine the social form of the city by preserving its continuity or stimulating departures from it.

Notwithstanding the semioticians outlook, a city is much more than a collection of signs. If planners speak of its legibility, the real city always reveals a stubbornly presemiological density. To insist on the citys legibility without considering this density and opaqueness distorts our knowledge more than enhancing it. It is also a defensive reduction of contingency, which seduces by making us feel in control of the obscurity that envelops the citys superficial transparency. In the opening chapter of The Man Without Qualities , Robert Musil describes the reactions of bystanders to a traffic accident. Looking at the scene, a lady feels discomfited until the man standing next to her says that trucks have an exceedingly long stopping distance. This comment brings her immediate relief: She had already heard this word in the past, but she did not know what stopping distance was and did not care to know. It was enough for her that through this word the horrible accident could be brought into some kind of order and turned into a technical problem, which no longer confronted her immediately (Musil 11). Technical terms seem to reinsert anxiety-arousing experiences into logic, and this may well be one of urbanisms critical functions. By organizing experience into an apparent structure, linguistic mediation allows us to read the city in a numbed state of indifference to its indeterminate aspects. Yet on the margins of the code there is room for disorder and, according to Richard Sennett ( The Uses of Disorder ), pragmatic reasons for it as well.

Strictly speaking, urban legibility depends on the existence of textual continuities. If the city is readable and may be spoken of as a text, it is because it functions as the semantic space for a number of interlocking discourses. the two forms in which alone this can legitimatelythat is, with a guarantee of permanencebe done (A Berlin Chronicle 5). The first form, which Benjamin abstains from emulating, is Prousts Recherche . The second, which he does not identify, can only be Baudelaires clippings of city life in his Spleen de Paris and Petits pomes en prose , the format that underlies Benjamins snapshot technique in One-Way Street and other city texts up to Passagen Werk . Thus one city may mediate the memories of another, and literature (amply understood) may provide the only access to the urban unconscious. Valentin Volosinov said roughly the same thing when he asserted that the sign always refers to another sign, and that consciousness can only emerge with the material presence of signs. As inmates of language, we become aware of the city as an ultra-encoded environment, even if this reality turns out to be semiologically disheveled and requires unending interpretation.