Publication of this book was supported by grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

and from the L. J. and Mary C. Skaggs Folklore Fund.

2017 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017950623

ISBN 978-0-252-04128-0 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-252-09988-5 (e-book)

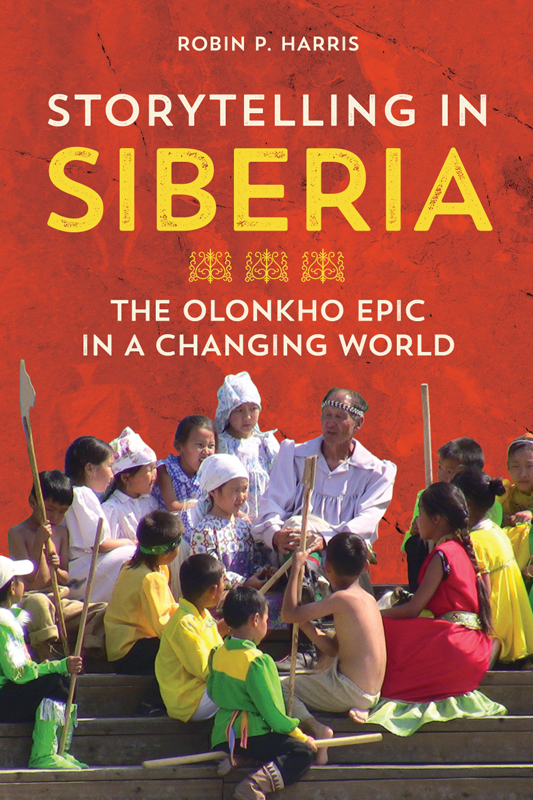

Cover illustration: Semn Chernogradskiy at the Third Ysyakh

of Olonkho in Borogontsy (2009). Photo by William Harris.

To my husband, Bill, whose enduring support and encouragement made this book possible, whose video skills masterfully captured the interviews during my fieldwork, and who changed my life forever by bringing me to Siberia.

Notes on Transliteration from Russian and Sakha

In quoted text, transliterations from Sakha and Russian remain as spelled in the source. In other cases, I use the Library of Congress system for transliteration, with a few minor adaptations for clarity and ease of reading for non-Russian speakers:

* Representations of the Russian letters transliterated as iu, ia, and ts, as well as the Sakha ng, do not include ligatures.

* The soft-sign diacritic [] is also omitted, and the letter [] (so-called soft ), which appears frequently at the end of Russian words, is omitted after y and otherwise changed to i.

With those caveats, the romanization of transcribed words follows the chart below. Additional exceptions include words with strong precedence in print for another spelling, such as toyuk rather than toiuk, Yakutsk rather than Iakutsk, and Nurgun rather than Niurgun in Nurgun Botur; and names for which people indicated a preferred spellingfor example, some people prefer to include the Y with the e at the beginning of their name (e.g., Yefimovich rather than Efimovich) and also between two e vowels within a name (e.g., Alekseyev, Andreyevna).

| a |

| b |

| v |

| g |

| d |

| e |

| zh |

| z |

| i |

| k |

| l |

| m |

| n |

| o |

| p |

| r |

| s |

| t |

| u |

| f |

| kh |

| ts |

| ch |

| sh |

| shch |

| y |

| iu |

| ia |

| gh |

| ng |

| h |

The Library of Congress website provides standard romanization charts for various languages at http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/roman.html. For Russian, see http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/russian.pdf; for Yakut (Sakha), consult http://www.loc.gov/catdir/cpso/romanization/nonslav.pdf.

Acknowledgments

A myriad of relationships, both professional and personal, undergird and energize a project such as this book. It is therefore with immense gratitude that I acknowledge the crucial role of my colleagues, graduate students, and valued friends connected to GIALs Applied Anthropology Department and its Center for Excellence in World Arts: Wendy Atkins, Kevin Calcote, Cory Cummins, Brad Keating, Michelle Petersen, Laura Roberts, Mary Saurman, Julie Taylor, Doug Tiffin, Pete Unseth, Steve Walter, and the rest of the faculty and staffthank you for your encouragement and support, and for giving me the freedom in my schedule to complete this book. A special thanks to the graduate students who helped with transcribing my extensive reading notes (Julie Johnson, Rabea Saad, and Sarah York), and to Kerry Payton, who duplicated in Finale the incredibly complicated olonkho transcriptions of N. N. Nikolaeva. I am grateful as well for the time invested by my teaching colleague Neil Coulter, who read the entire manuscript and provided valuable input. Two Dallas-based colleagues played particularly significant roles in the creation of this book: Brian Schrags example of integrated faith, purposeful creativity, and rigorous scholarship in ethnoarts inspires me in my academic work, and Katie Hoogerheides numerous hours of attention to my prose greatly refined both my ideas and their written expression.

I owe an enormous debt of gratitude to my family, whose unflagging support made the many years of research and writing for this project possible. I am particularly grateful for the encouragement of my husband, Bill, to whom this work is dedicated; my intrepid offspring, James and Katherine, who spent their childhood in Russia; and my parents, Bob and Joyce Persn, who instilled in me the love for music, cross-cultural work, and lifelong learning that set me on this road.

If it were not for the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant and the Folklore Studies in a Multicultural World program, this book would never have come to fruition. Im deeply grateful for the attentive support and reliable advice of my editor, Laurie Matheson, throughout the process, and to Dorothy Noyes, who gave invaluable feedback on some early drafts. Im also profoundly grateful to Ted Levin, whose careful reading and suggestions improved the book in significant ways. In addition, his engagement with and advocacy for scholars and musicians in the Russian Federation and across Central Asia provide a model to which I aspire.

In addition to the invaluable support and guidance of the faculty at the University of Georgia Athens during my dissertation work, Im particularly grateful to my committee members David Haas and Elena Krasnostchekova for their insistence that this research be published, and to my dissertation advisor, Jean Kidula, whose unerring critical insight, personal example of outstanding scholarship, and steady support during my studies and beyond have given me the courage to persevere and aim high. I also appreciate the financial support received from the University of Georgia through the Deans Award and a travel grant from the UGA Research Foundation, which ameliorated the high cost of fieldwork in Siberia.

I share the credit for this work with many Sakha collaborators, hosts, respondents, and colleagues: Irina Aksyonova, Anna Andreyeva, Maria Borisova and her son Mikhail, Vladimir Burnashev and his wife Tatiana, Olga Charina, Ekaterina Chekhorduna, Semyon Chernogradskii, Stas Efimov, Sargylana Elyasina, Dora Gerasimova, Vasilii Illarionov, Vasilii Ivanov, Dmiitri Krivoshapkin, Elena Kugdanova-Egorova, Anastasia Luginova, Boris Mikhailov, Svetlana Mukhoplva, Alina Nakhodkina, Nadezhda Orosina, Olga Osipova, Elena Protodiakonova, Ekaterina Romanova, Spiridon Shishigin, Tatiana Semnova, Gavriil Shelkovnikov, Liubov Shelkovnikova, Elizaveta Sidorova, Vera Solovyeva, Maria Stepanova, Valentina Struchkova, Aleksandra Tatarinova, Pyotr Tikhonov, Sergei Vasiliev, Dekabrina Vinokurova, Agafia Zakharova, and Yury Zhegusov. Their hospitality, encouragement, openness, willingness to recount memories and opinions, and generous sharing of resources and research summaries have supported this research at every step. This project stands on their shoulders. In that regard, I would especially like to thank the Kononov family, Valerii and Maria, who rendered invaluable logistical help and insight during my fieldwork trips to villages around Yakutia, and olonkhosuts Pyotr Reshetnikov and Nikolai Alekseyev, who not only recounted their stories and performed for me, but also hosted me during my stay in their respective villages.