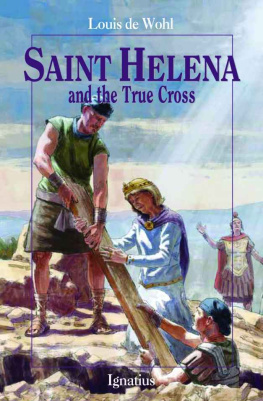

SAINT HELENA

AND THE TRUE CROSS

SAINT HELENA

AND THE TRUE CROSS

Written by Louis de Wohl

ILLUSTRATED BY BERNARD KRIGSTEIN

IGNATIUS PRESS SAN FRANCISCO

Original edition 1958 by Louis de Wohl

All rights reserved

Published by Farrar, Straus and Cudahy, Inc., New York

Published simultaneously in Canada by Ambassador Books, Ltd., Toronto

Published with ecclesiastical approval

Ignatius Press edition published by arrangement with

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Inc., New York

Cover art by Christopher J. Pelicano

Cover design by Riz Boncan Marsella

Published in 2012 by Ignatius Press, San Francisco

All rights reserved

ISBN 978-1-58617-598-6 (PB)

ISBN 978-1-68149-716-7 (EB)

Library of Congress Control Number 2011930700

Printed in the United States of America

Printed by Thomson Shore, Inc., Dexter, MI

CONTENTS

1

THE BURNING OF BRITAIN

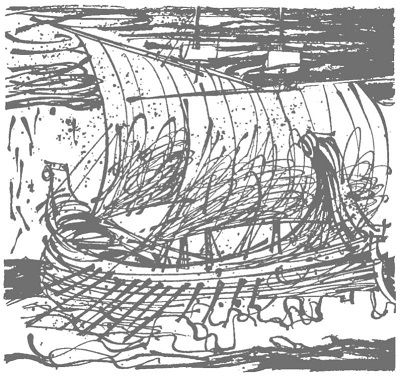

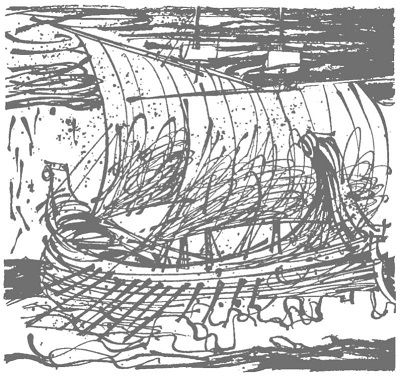

PRINCES HELENA stood on top of the chalk-white cliffs, watching a ship slowly vanish on the horizon.

The curly-haired thirteen-year-old boy at her side asked impatiently, Mother, when is Father coming back?

I dont know, Constantine. Its a long way from Britain to Rome; itll take weeks. Then he must talk to the emperor, and then he must travel all the way back here.

The emperor has sent for him, hasnt he?

Yes.

That means he needs Father. The boy smiled proudly.

Quite right. Helena too smiled. The boy was growing more like Constantius every daythe same short nose and strong chin, the same firm outline of the eyebrows, almost straight. The same pride too, though there were people who held the opinion that the boy had inherited that from both his parents.... Well, perhaps he did.

She pressed her lips together. Pride was an essential thing. Without pride, no ambition. Without ambition, no high position in life. As a young girl she thought that it was something to have the King of the Trinovants as a father, to be a princess, and to have gray-bearded men bow to her with the respect due to her rank.

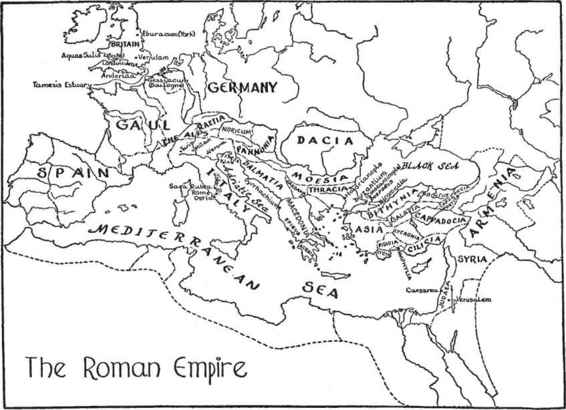

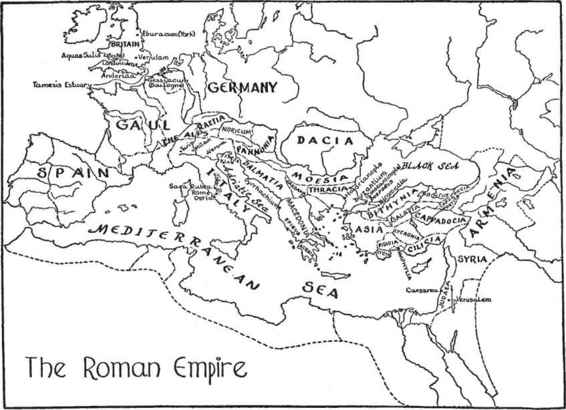

She used to think and speak with disdain of the Romans who thought they could rule Britain just because they had stationed a few legions here. She studied Roman history. Surely the Romans were no longer what they were when Gaius Julius Caesar landed on the shores of Britain. And she used to dream that one day she would unite the tribes and lead them against the Roman occupation forces.

But that was before she met the young Tribune Constantius, to whom all Britons were poor, ignorant barbarians and a princess of the Trinovants no more than an amusing novelty. They had clashed, inevitably; equally inevitably, they had fallen in love. Her father and Constantius military superior had agreed to the marriage, both for exactly the same reasons: the security and peace of the island. And through Constantius she had learned to admire Rome, even to love it in her own peculiar way. For Rome, despite all signs of degeneration, was still ruling the world, and only Rome was the source of real power.

To Constantius, the gates of that power were wide open. He came from one of the oldest families of Rome. He even had imperial blood in his veins. And he was an excellent soldier. All his wife had to do was stimulate his ambition still further and give him a male heir.

Helena had done both. Less than a year after their marriage, Constantine was born. Six years later Constantius was promoted to the rank of legate, or general, and given command over the whole of Southern Britain. And now the new emperor, Maximian, had sent for him. This could meanit very likely did meanfurther promotion: the general command of another province, perhaps, or the supreme leadership in the Persian campaign. The possibilities ranged from Britain to Persia, from Germany to Egypt!

The night before he sailed, she had told him, Accept whatever it is if it furthers your career. Dont think for one moment that I might feel homesick for Britain. Dont think of me at all. The only thing that matters is your careeryour position, and that of our son.

Rome had two emperors now. Even the formidable Diocletian could no longer cope with the herculean task alone and had therefore raised Maximian to equal rank with himself. Maximian was a soldier. Well, so was Constantius...

The ship was gone.

Helena drew her cloak closer around her. Let us go, she said, shivering a little.

They walked back to the road where the Centurion Favonius was waiting with the carriage. Marcus Favonius was a sturdy man with the arms and shoulders of a gladiator. He had made his way up from the ranks in the Twentieth Legion, and Constantine was delighted when his father chose that experienced fighter to be his trainer in military matters. Favonius had fought in Numidia and at the German frontier, he had won two silver discs for bravery, and he was the best man with sword and shield in the whole of Britain.

Helena liked the man because he was conscientious, reliable, and utterly loyal. Were going home, Favonius, she said. No, you take the reins this time. Im a little tired.

Very well, Domina.

A quarter of an hour later they were back at the villa, which had been the private residence of half a dozen Roman commanders of Southern Britain.

The day passed like every other day. The slaves were singing at their work in the garden. Constantine had his fencing lesson with Favonius. In the afternoon a little rain fell. One of the maids had to be punished for breaking a vase. The major-domo came to receive the list of invitations for the next week. There were fewer of them now, naturally. All official functions had been taken over by Tribune Valerius, the commander in charge until Constantius returned.

Helena sighed and then became angry with herself. This was the first day of many to come, of very many. She had always despised the clinging-vine type of officers wife, fretting and nervous when her husband was away on duty. That was all that had happened. Constantius had been called away on duty, and it was not even dangerous duty.

Yet she had to force herself to be even-tempered with Constantine. She ate very little at dinner and retired early. When sleep would not come, she became angry with herself again. I am nervous, she thought, and I am fretting. What miserable creatures women are....

When at long last she fell asleep, she dreamed that Constantius was being shipwrecked. He saved himself by clinging to a large piece of wood and landed on some island, where he was taken prisoner by soldiers in Roman uniforms. She remembered the dream when she woke up. Perhaps she ought to ask a druid whether it meant anything? No, she would not. Priests always saw an evil meaning in dreams, except when one paid them well.

At noon she saw the cloud. It was not an ordinary cloud, but a column of black smoke rising behind the hills in the direction of Anderida.

Something was burning there.

She stepped out onto the terrace to get a better view and found that there was a second column of smoke a little farther to the west.

Favonius came up from the garden.

Look at that, Favonius. What do you make of it?

The centurion looked, blinked, and looked again. I dont like it much, Domina, he said slowly.

Next page