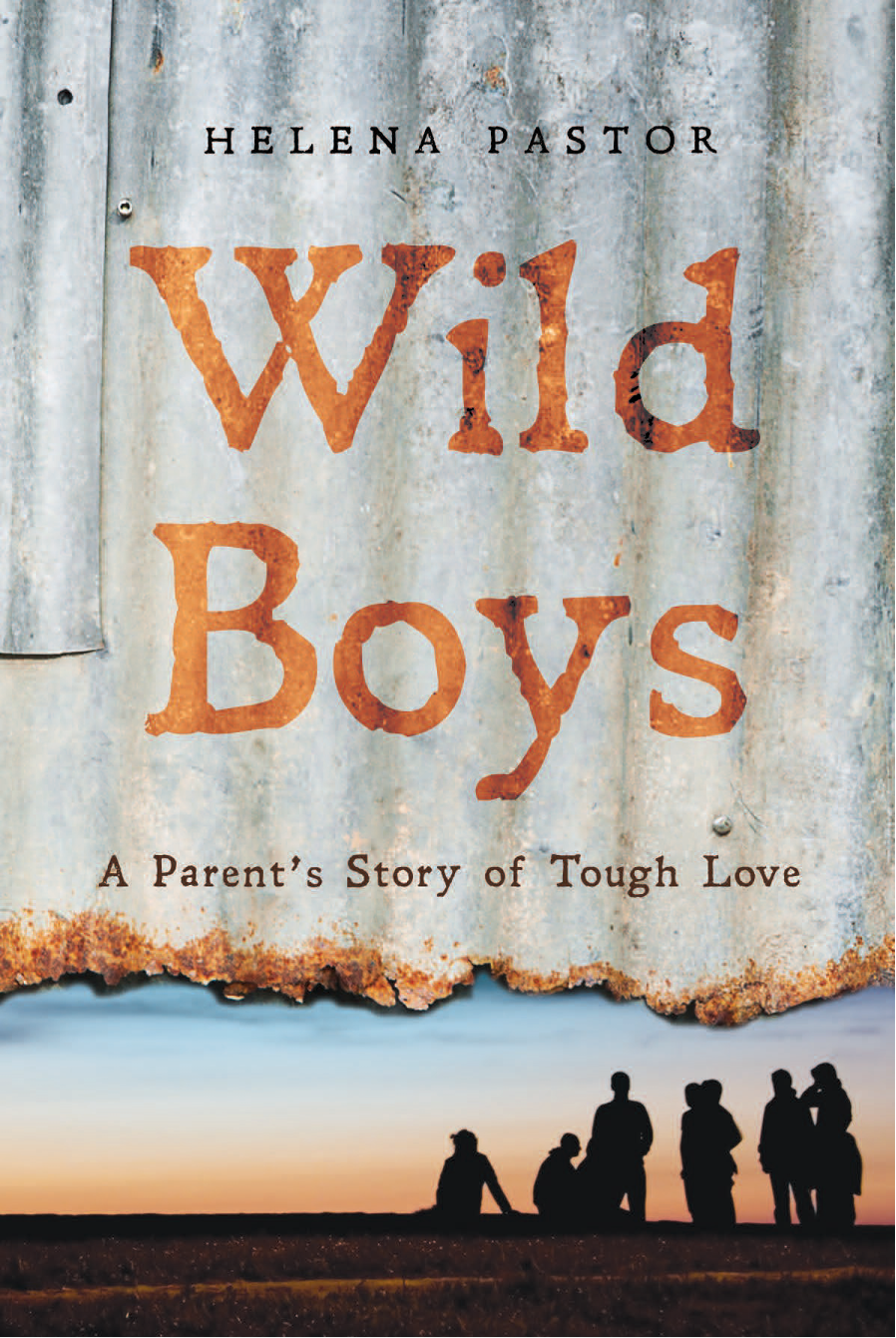

Helena Pastor is a Dutch-Australian writer who is passionate about the social justice possibilities of her work. Through memoir and fiction, she hopes to influence the way people think and feel about topics including troubled youth, pregnancy and birth choices, growing up in an immigrant family, and recovering a lost Jewish identity. Her writing has attracted two Australian Society of Authors Mentorships, along with a number of residencies at Varuna Writers House and Bundanon. She has extensive experience as an educator, and has worked with groups ranging from Bosnian refugees to university-level creative writing students. Helena is also a songwriter and performer. She lives in Armidale and has four sons and a grandson.

Helena Pastor is a Dutch-Australian writer who is passionate about the social justice possibilities of her work. Through memoir and fiction, she hopes to influence the way people think and feel about topics including troubled youth, pregnancy and birth choices, growing up in an immigrant family, and recovering a lost Jewish identity. Her writing has attracted two Australian Society of Authors Mentorships, along with a number of residencies at Varuna Writers House and Bundanon. She has extensive experience as an educator, and has worked with groups ranging from Bosnian refugees to university-level creative writing students. Helena is also a songwriter and performer. She lives in Armidale and has four sons and a grandson.

For Pup and Joey with love,

for my boys at home and elsewhere,

and for Bernie and all the boys at the shed.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

In the bathroom of the bakery house, the bare-chested boxer fronts up to the mirror. He adjusts his stance, raises his fists and tucks his chin. His face takes on a faraway look, like hes back in the ring perhaps, in another time and place. His hands flash through the air, accompanied by short tight breaths. Phh phh phh goes the right fist, phh phh goes the left. Right phh. Left phh phh . The punches and breaths have a rhythm, a timbre, like music. His children wander in and use the hand basin, where they brush their teeth and prepare for bed with the familiar sound of phh phh coming from the other side of the bathroom. They know not to interrupt their father while he boxes with his other self.

*

I take out a photo of Joey and his opa at the beach, and put it on the wall above my computer. Theyve just made an extravaganza of a sandcastle and are sitting back on the sand, looking pleased with themselves. When I was a child, my father built me similar sandcastles huge mounds covered in turrets and decorated with shells that stood grandly on the shore. He was always good like that with Joey, too, even though Joey didnt make it easy for him. When Joey was a baby, he often struggled and screamed at sleep-time, but my father would sit in the room with him and play classical guitar until Joey fell asleep. The crying never seemed to bother him. As a toddler, Joey liked to run away from his opa when they were at the beach or the park and my father, who had bad knees, couldnt chase after him. Hed be calling for him to come back, petrified that Joey would fall from the rocks into the sea, or run across the road into traffic. One time, when Joey was eight, he and my father were playing cards, and when Joey didnt win, he kicked his opa in the leg. My father didnt get angry. He just said in his thick Dutch accent: That was not a very nice thing to do, Joey. You cant always win in life.

My father wasnt always so calm and measured. He was once a boxer, and a baker, and the master of any fight with words. After a long day in the bakery, he would hang over his plate at the end of the dinner table and bait and criticise my three siblings, who were already teenagers by the time I was five. My fathers recurring themes centred on how ungrateful his children were, how they didnt help enough around the house or try hard enough at school, and how their friends were the wrong sort of people. Is this what we came to Australia for? he would ask. I lived through years of yelling and arguments over dinner, watching as my siblings tried to oppose my father, while my mother sat by and said little. Every time, my brothers or my sister big, strong teenagers crumpled before him, often running from the table in tears.

As a child, I cried to our corgi. I curled up with him in his kennel as the fights raged inside the house. By the time I was a teenager, I knew not to fight.

I

AutumnWinter 2007

Joining the pack

The Iron Man Welders meet on Sundays in an old council depot on the edge of Armidale, a university town in northern New South Wales. I recently volunteered to help out with this program for troubled teenage boys, an initiative led by a maverick youth worker called Bernie Shakeshaft. Not that Im a welder or a youth worker Im a trained English language teacher. But I only work part-time these days because Im also a part-time PhD student, a wife, and a mother of four boys who range in age from two to sixteen. I was just looking for some answers.

About a year ago, Bernie had a vision of a welding project that would build on the strengths of a group of young men who had dropped out of high school but werent ready for work. He asked the Armidale community to help out. The local council offered him the depot, which had once been a welding workshop and was lying empty, as if waiting for Bernie and the boys to come along and claim it.

There was nothing in the huge shed, not even a power lead. The boys turned up each weekend and worked hard to clean and create their own workplace. They borrowed nearly everything, from brooms to welding equipment, and started collecting recycled steel for the first batch of products they planned to make and then sell at the monthly markets. Local welding businesses gave scrap metal; people lent grinders, extension cords and old work boots.

Then the money started coming in. A local builder forked out the first five hundred dollars. The bowling club gave a thousand and a steel-manufacturing business donated a MIG welder. The credit union offered to draw up a business and marketing plan, organised insurance, and contributed a thousand dollars for equipment. A nearby mine donated another thousand and raised the possibility of apprenticeships for the boys, and the New South Wales Premiers Department handed over a grant worth five thousand dollars. It seemed like every week Bernie and the boys were in the local paper, celebrating some new success.

I saw a photo of Bernie in the paper, surrounded by a group of boys, their faces beaming with happiness and pride. At the time, I was having a lot of trouble with my sixteen-year-old son, Joey, who had left home but boarded in a house nearby. I was worried about him and didnt like the way he was drifting through life no job, no direction, living off Centrelink payments, sleeping in till midday. As I looked at the happy faces in the photo, something stirred inside me. I wanted to be part of it: the Iron Man Welders.

The next day I heard Bernie on the radio, seeking community support for the project. Well take any positive contribution, he said. His words sounded clipped and tight, like he wasnt one for mucking around. Whether youve got a pile of old steel or timber in your backyard, or if youve got an idea, or if you like working with young people and youre prepared to come down to the shed and work one-on-one with some of these kids

On impulse I rang. I was interested in learning more about boys and alternative forms of education for both personal and academic reasons but Id never used power tools, let alone done any welding. I liked bushwalking and baking cakes. I enjoyed order, cleanliness, silence. What was I thinking?

Right from the start, though, the boys were gracious in accepting a 41-year-old woman into their grimy world. With my short brown hair, and in my King Gees and work boots, I dont stick out too much. The boys find easy jobs for me to do like filing washers for candleholders or scrubbing rust off horseshoes. I sweep the floor, watch whats going on, listen to what they want to tell me. The fellas who come along are the sort of misfits you see wandering the streets of any country town, with nothing to do, nowhere to go. Once, I might have crossed the street to avoid them.

Helena Pastor is a Dutch-Australian writer who is passionate about the social justice possibilities of her work. Through memoir and fiction, she hopes to influence the way people think and feel about topics including troubled youth, pregnancy and birth choices, growing up in an immigrant family, and recovering a lost Jewish identity. Her writing has attracted two Australian Society of Authors Mentorships, along with a number of residencies at Varuna Writers House and Bundanon. She has extensive experience as an educator, and has worked with groups ranging from Bosnian refugees to university-level creative writing students. Helena is also a songwriter and performer. She lives in Armidale and has four sons and a grandson.

Helena Pastor is a Dutch-Australian writer who is passionate about the social justice possibilities of her work. Through memoir and fiction, she hopes to influence the way people think and feel about topics including troubled youth, pregnancy and birth choices, growing up in an immigrant family, and recovering a lost Jewish identity. Her writing has attracted two Australian Society of Authors Mentorships, along with a number of residencies at Varuna Writers House and Bundanon. She has extensive experience as an educator, and has worked with groups ranging from Bosnian refugees to university-level creative writing students. Helena is also a songwriter and performer. She lives in Armidale and has four sons and a grandson.