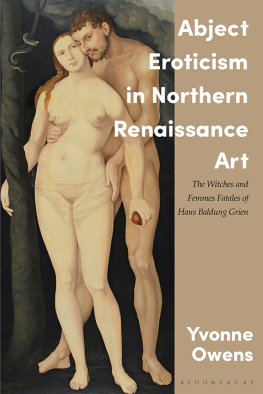

ABJECT EROTICISM IN NORTHERN RENAISSANCE ART

ABJECT EROTICISM IN NORTHERN RENAISSANCE ART

The Witches and Femmes Fatales of Hans Baldung Grien

YVONNE OWENS

Chapter 1 was previously published as Pollution and Desire in Hans Baldung Grien: The Abject Erotic Spell of the Witch and Dragon. Images of Sex and Desire in Renaissance Art and Modern Historiography: 180206. Routledge, 2017.

An early version of Chapter 3 was published as The Saturnine History of Jews and Witches. Preternature: Critical and Historical Studies on the Preternatural 3.1 (2014): 5684.

CONTENTS

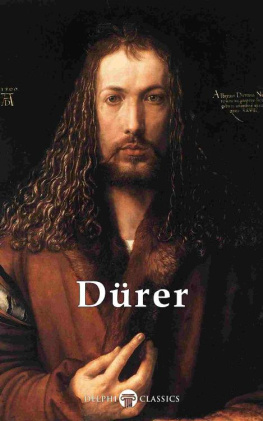

Hans Baldung Grien is the most eccentric member of a remarkable generation of painters working in Germany at the eve of the Reformation. Although each was highly individual, and strove to be so, all stood under the shadow of one towering master in their midst. It was in response to Albrecht Drer and his transformative activities that Baldung, Lucas Cranach the Elder, Matthias Grnewald, Albrecht Altdorfer and Hans Holbein the Younger pursued their craft. Incorporating Italian and Netherlandish stylistic impulses into his local South German idiom, and more crucially concentrating his skills and huge artistic energies on the new medium of print, Drer projected to his competitors not only a new style and expanded thematic repertoire, but also a novel business model, one that included the cultivation of an individualistic approach to art. Henceforth, by making singular engravings, woodcuts and etchings, ambitious artists of the culture would seek to disseminate their original inventions and (through monograms and signatures) their identity to a new global audience.

Baldung was unique among the major German artists of his generation in having come of age as an assistant in Drers workshop in Nuremberg. His struggle to distinguish himself had to be undertaken at close range to Drer, and this plus an ambition comparable to his masters caused in Baldungs art a certain wilful strangeness: we see him early on cleverly subverting Drers products, often by intensifying destabilizing elements already there in his model. Also unusual was his background. His earliest self-portrait (arguably also his Opus One) executed in pen and ink heightened with pink and white on bluish green prepared paper was probably made in Strasbourg prior to his move to Nuremberg. It shows a virtuoso supremely self-conscious of his skill. Unique among northern artists, Baldung came from a family of well-to-do, university-trained lawyers and medical doctors. Like his older Netherlandish contemporary and fellow-eccentric Hieronymus Bosch, who married into money, he probably did not depend on his art for income but, in his maturity, pursued his craft partly as a patrician pastime. Close connections with the medical and juridical thinking of the time also played a key role in Baldungs most eccentric and famous creations: his paintings, drawings and prints of witches.

Strangeness permeates Baldungs entire oeuvre. His religious pictures estrange their stories, as if the artist assumed that unhomeliness was both a pious expression of awe and an aesthetic strategy. Even his portraits deliberately endow their sitter with an uncanny charge, often through a sideways glance directed at the viewer. But it is in his macabre and demonic imagery, in depictions of death, witchcraft and the nefarious, catastrophic relations between Eve and Adam, that strangeness finds its creative arena and ideological alibi. In Baldungs world a realm marked out by his early chiaroscuro woodcuts The Fall of Human Kind and Witches Sabbath and rendered intensely personal in his bizarre last masterpieces The Bewitched Stable Groom and the Wild Horses series everything is corrupted by the original trespass in Eden. Not only the evil agents in his pictures, but also his paintings, drawings and prints themselves, in showing evil, as well as the viewer in responding to evil, are ineluctably and universally tainted by sin. And again in Baldungs world, that sin is, and originally was, sexual in character: it was Adams lust for Eve, preconditioned by Eves corrupting carnality, that caused the Fall, and that is thenceforth inherited by humanity as their uncontrolled lustfulness. Christ, the Virgin, the saints and martyrs are not naturally available in such a world. Ostensibly pure, their difference from the defilement that permeates both the artist and his viewers gets therefore expressed as strangeness, hence, perhaps, the oddest works by Baldung that (as Leo Steinberg plausibly argued for a strange woodcut by Baldung showing St. Anna touching as if somehow expertly to test their virility of the Christchilds genitals) feature sexualized images of the Virgin and Christ.

Although Drer had already launched a rich iconography of witchcraft through early engravings, it was Baldung, more than any artist of the tradition, who shaped Europes destructive image of witches and what they do. And one of the astonishing and sinister features of his achievement was to engineer in his viewers precisely a terrifying uncertainty about what witches are and do. Drawing from the phantasmagorical evidence of contemporary witch trials and inquisitorial treatises, and adding to this a composite of ancient and medieval witch lore, he not only crafted and (through prints) widely disseminated an elaborate, definite and compelling demonic imaginary; he built into this imagery a certain all-pervasive doubt. This was not a doubt that witches are real: giving form to fantasy, his art confirmed to his public the reality of a hostile conspiracy lodged at the heart of the social order, indeed an enemy established within the hearth and home, through the omnipresence of women in lay and even clerical life (he slyly marks his priestly viewers as lustful and philandering). The doubt that Baldung sowed was about himself and his intentions, and about his viewers and their responses, as he went about representing the activities and (more troublingly) the artifices of the enemy Other. In the imaginary that he creates and disseminates, witchcraft is itself an art, one that utilizes images (symbols, signs, spectres, spells) for its dark purposes. Because these images have as their purpose our destruction the we being an imagined audience of beleaguered men they confront us not as legible symbols but as enigmas. And yet, this hostile arsenal also was semantically more transparent to its original viewers, the elite art lovers in Baldungs Strasbourg and beyond, than they are to us today. And it is among other things this important deficit in our contemporary understanding of Baldungs engineered enigmaticness that Yvonne Owens has so brilliantly overcome.

One of many puzzling features of Baldungs scenes of witchcraft is a ubiquity of fumes, the origins and nature of which are deliberately obscure. Baldung links these fumes formally to other ubiquitous motifs, specifically witches hair, the moss on trees, and the bodies and tails of horses. Yvonne Owens has identified what brings these elements together, and it would be to do a disservice to her exposition that follows to spoil the surprise at learning, through the book that follows, how cunningly Baldung has crafted his enemy imagery. Suffice to say, not only are details in many of the artists key works resolved; and not only are the basic subjects clarified, and their literary and philosophical sources for the first time discerned. Owens has also grasped the global outlook of this artist, as a perspective founded on a certain terrified and terrifying antagonism to women. In Drers wake, artists recognized that their professional fortunes depended on an intensified individuality. This led to certain strategies of specialization: Altdorfer specialized in landscape, Holbein in portraiture, Cranach in didacticism bifurcated by eroticism. It may not be an exaggeration, then, to say that Baldung specialized in misogyny. One peculiar fact in the chronology of the artists oeuvre attests to this. Baldung first ventured into the new, spectacular and technically exacting medium of chiaroscuro woodcut through his scene of a Witches Sabbath, and he followed that toxic creation with his equally ambitious chiaroscuro print of Adam and Eve, implying that, in terms of the internal logic of his development, as well as the conversation he sets up between his works, the biblical event in Eden was, for him, but a prequel to the burgeoning evil of the present day, with Eve as the first witch, and witches as Eves present progeny. Where some scholars have doubted that Baldungs erotic female nudes are all witches, Owens suggests, correctly, that witches are everywhere, including in the Holy Family, and that the entirety of his output, the whole of his transfigured and transfiguring vision, is nefariously charged. The nature, aim and terrifying scope of this specialty are the themes of Owens remarkable book.

Next page