Author: Hans-Jrgen Dpp

Translators: Philip Jenkins, Jane Rogoyska, Dr. Jane Susanna Ennis, Susana M. Steiner

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

Paul Avril, copyright reserved

Hans Bellmer, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ ADAGP, Paris

Bouliar, copyright reserved

Paul-Emile Bcat, copyright reserved

Bergman, copyright reserved

Louise Bourgeois, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/VAGA, New York

Courbouleix, copyright reserved

Jules Derkovits, copyright reserved

Erler, copyright reserved

Michel Figensten, copyright reserved

Margit Gaal, copyright reserved

Javier Gil, copyright reserved

Godal, copyright reserved

David Greiner, copyright reserved

Hegemann, copyright reserved

Lobel-Riche, copyright reserved

Martin von Maele, copyright reserved

Merenyi, copyright reserved

De Monceau, copyright reserved

Jean Morisot, copyright reserved

Ornikleion, copyright reserved

Hans Pellar, copyright reserved

Armand Petitjean, copyright reserved

Reunier, copyright reserved

Andr-Flix Roberty/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

Otto Rudolf Schatz, copyright reserved

Louis Berthomme de Saint-Andr/Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

Attila Sassy, copyright reserved

Otto Schoff, copyright reserved

Roland Topor, Artists Rights Society, New York, USA/ADAGP, Paris

Troyen, copyright reserved

Marcel Verts, copyright reserved

Gerda Wegener, copyright reserved

Zll, copyright reserved

ISBN 978-1-78310-751-3

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lie with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

Hans-Jrgen Dpp

Erotic Fantasy

Contents

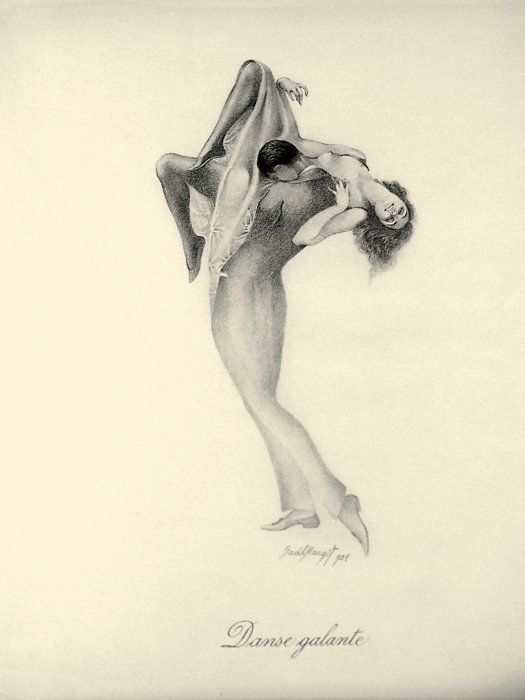

1. Margit Gaal, 1920.

Introduction

Loves Body

Reflections on Fragmentation of the Body

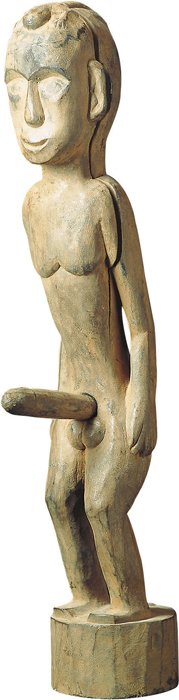

The subject of the essays in this book is not the body as a whole, but rather its separate parts. As we fragment the body, we make its parts the subject of a fetish. Each individual part can become a focus of erotic passion, an object of fetishist adoration. On the other hand, the body as a whole is still the sum of its parts.

The partitioning that we carry out here brings to mind the worship of relics. Relic worship began in the Middle Ages with the adoration of the bones of martyrs and was based on the belief that the body parts of saints possessed a special power. In this respect, each fetishist, however enlightened he pretends to be, pays homage to relic worship.

At first, this dismemberment only happened to saints, in accordance with the belief that in paradise the body will become whole again. Only later were other powerful people such as bishops and kings also carved up after their deaths. In our cultural survey of body parts, we are particularly concerned with the history of those with erotic significance. Regardless of whether their significance is religious or erotic, they all attain the greatest importance for both the believer and the lover because of the attraction and power inherent in them. This way, fetishist heritage of older cultures survives in both the believer and the lover.

O Body, how graciously you let my soul

Feel the happiness, that I myself keep secret,

And while the brave tongue shies away,

From all that there is to praise, that brings me joy,

Could you, O Body, be any more powerful,

Yes, without you nothing is complete,

Even the Spirit is not tangible, it melts away

Like hazy shadows or fleeting wind.

Anatomical Blazons of the Female Body appeared in 1536, a newly printed, multi-volume collection of odes to each body part individually. These poems, praising parts of the female body, constituted an early form of sexual fetishism. Never, wrote Hartmut Bhme, does it sing the whole body, let alone the persona of the adored, but rather it is a rhetorical exposition of parts or elements of the body. In these poems, head and womb represented the central organs. It was to be expected that representatives of the church scented a new form of idolatry in this poetic approach and identified a sinful indecency in this depiction of female nakedness:

To sing of female organs,

To bring them to Gods ears,

Is madness and idolatry,

For which the earth will cry on Judgement day.

This is how such condemnation is expressed in a document entitled Against the Blazoners of Body Parts, written in 1539 From this perspective, the Blazons would be womanless.

The poetic dismemberment of the female body satisfies fetishist phallocentrism, which, as Bhme points out, also lies at the root of male aggression. Today it would be called sexist.

A woman is a conglomerate of sexual-rhetorical body parts, desired by men: one beholds the female body in such explicit detail that the woman herself is negated. A courtly, cultivated dismemberment of a woman is celebrated in the service of male fantasy. Is the female body thus reduced to a plaything of lust?

Bhmes analysis echoes much of contemporary feminist critique: The corporeal should be given homage only when it is united with personality, as if the body itself was something inferior.

What Bhme refers to as phallocentrism, can be observed even in the context of advanced cultures: the progress of civilisation has been accompanied by an ever-increasing alienation of the body this process is repeated in each stage of history.

The lustful preoccupation with the body is the primary interest of a child. Children are able to experience desire in the activity of their whole body to a much greater degree than adults. In adults, this original, all-consuming childhood desire is focused in one small area the genitals. This is how Norman O. Brown describes erotic desire in The Resurrection of the Body

This dichotomy between body and spirit defines our culture. Dietmar Kamper and Christoph Wulf discuss this in their study of the destiny of the body throughout history and conclude that the historical progress of European imprinting since the Middle Ages was made possible by the distinctively Western separation of body and spirit, and then fulfilled itself as spiritualisation of life, as rationalising, as the devaluation of human body, that is, as dematerialisation.

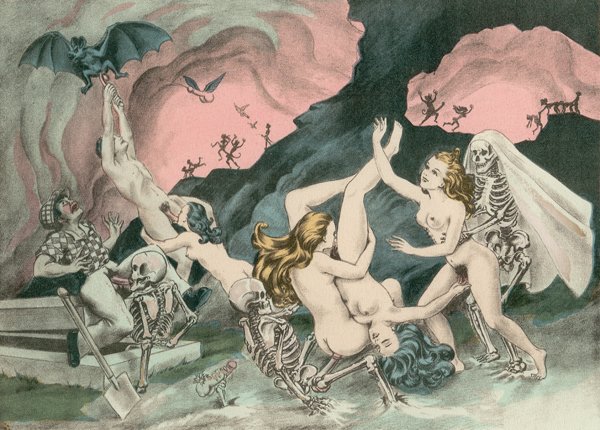

2. Anonymous, 1940.

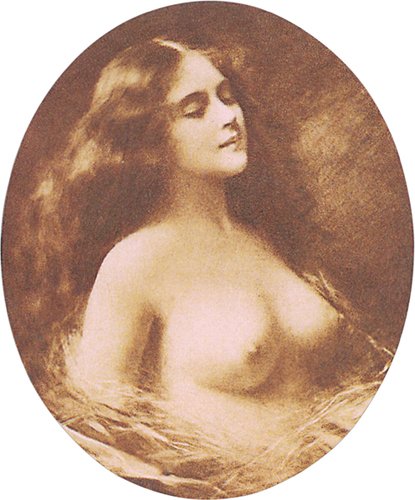

3. Intense Pleasure, 19 th century. Photograph.

Next page