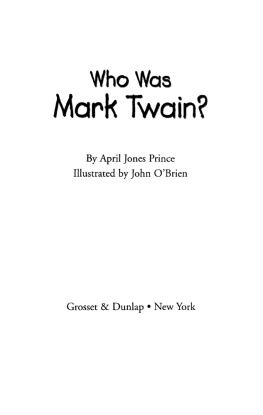

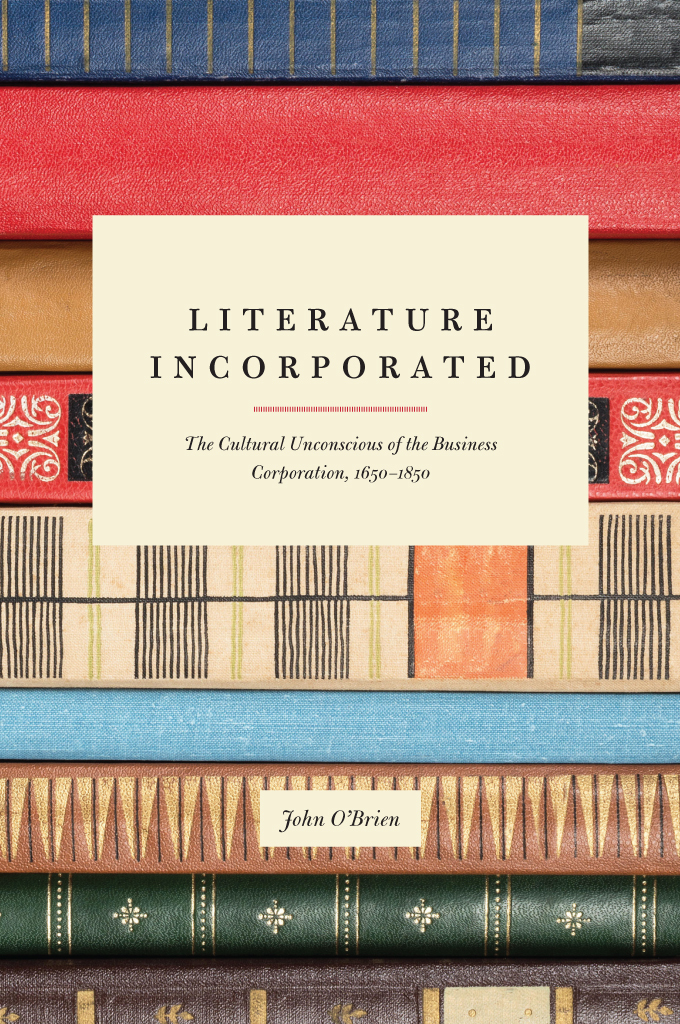

Literature Incorporated

The Cultural Unconscious of the Business Corporation, 16501850

John OBrien

The University of Chicago Press

CHICAGO & LONDON

JOHN OBRIEN is associate professor and the NEH Daniels Family Distinguished Teaching Professor in the Department of English at the University of Virginia. He is the author of Harlequin Britain and the editor of Susanna Centlivres The Wonder.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2016 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2016.

Printed in the United States of America

25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-29112-3 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-29126-0 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226291260.001.0001

The University of Chicago Press gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the University of Virginia toward the publication of this book.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

OBrien, John, 1962 author.

Literature incorporated : the cultural unconscious of the business corporation, 16501850 / John OBrien.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-29112-3 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-29126-0 (ebook) 1. Corporations in literature. 2. Businesspeople in literature. 3. Business literatureGreat Britain. 4. CorporationsGreat BritainHistory. 5. English literatureEarly modern, 15001700History and criticism. 6. English literature18th centuryHistory and criticism. 7. English literature19th centuryHistory and criticism. I. Title.

PR149.C667O37 2016

820.9'3553dc23

2015017769

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

The Corporation as Metaphor

The concept of incorporation as applied to social entities like a business venture is a figure of speech; more specifically, it is an instance of a rhetorical trope known as catachresis. Derived from the Greek for abuse or misuse, catachresis results when language fails to offer an obvious word choice to describe something. Henry Peachum, in his rhetorical handbook The Garden of Eloquence (1593), calls catachresis an abuse by means of which we give names to many things which lack names, as when we say, the water run, which is improper, for to run, is proper to those creatures which have feete, and not water which hath none.

Both the utility of and the discomfort with the figure of the corporation have been recurrent themes in its history. In Britain from the Middle Ages onward, towns, guilds, charitable organizations, universities, and the church were all understood to be incorporated institutions, bodies politic that transcended the limits of individual human bodies and persisted beyond single human life spans. The historian Ernst Kantorowicz traced how the thirteenth-century church began to make a distinction between the physical body of Jesus as made present in the Eucharist and the imaginary, metaphorical body of Christs church: Now... The Church, which had been the mystical body of Christ, became a mystical body in its own right... a mystical corporation. The monarchy was reconceptualized by this logic to create what Kantorowicz memorably described as the kings two bodies, the one fleshly and mortal, the other imaginary and immortal, occupied by a real person in the present tense but representing a collective interest (that of the state and its people) and aspiring always to transcend the here-and-now and reach toward eternity.

But the peculiar doubleness of the concept often prompted complaint in the early modern period, as it has ever since, and particularly so as the From its origins, the corporation has been a kind of offense to representation, a legal fiction whose abstraction seems to mystify as much as it defines the relationship between individuals and larger social entities.

Near the outset of his Grundrisse, the enormous series of notebooks that he compiled in order to systematize his study of political economy, Karl Marx ponders the utility of abstract concepts in political-economic thought. Concepts like population, exchange value, production, and labor (among others) seem necessary if the theorist aims to say anything specific at all. Hence Marx admires how Adam Smith took an immense step forward in isolating and objectifying labour as such as an abstract universality that enabled economists to imagine national wealth in terms more useful than those offered by the physiocrats, with their focus on the productivity of land, or by the adherents to the Mercantile System, with its focus on money in the form of bullion.

Just when he was beginning to fill the notebooks that are now known as the Grundrisse, Marx had every reason to be freshly aware of the centrality of companies to the transatlantic economic system. The Panic of 1857, a financial crisis that Marx welcomed as the spark that might lead to a revolution, was frequently seen at that time to have been set off by the failure of the New York City office of the Ohio Life Insurance and And to the (again, considerable) extent that the Grundrisse formed, as it was designed to, the foundation for Capital (1867), we can also observe that the abstraction Marxism owes some debt to a corporations failure.

What is striking, then, is how little Marx has to say about corporations in either text. It is as if, avidly reading and in turn contributing to the newspaper accounts in 1857 about the failures of insurance companies, banks, and other corporate institutions, Marx was determined to rise above the fray of the moment and conceptualize political economy in terms that were equally abstract but in his thinking more foundational: money, capital, labor. Corporations as such have very little place in Marxs classic descriptions of the economic system. The passing reference to them that we have seen in the Grundrisse, where he talks about modern joint-stock companies, suggests that Marx did not, at least at that point, understand the corporation very well. By 1857 the term joint-stock, which dates to the late seventeenth century, was an anachronism, as the corporations of the mid-nineteenth century well outstripped the joint-stocks of the past in sophistication, capitalization, reach, and independence from the authority and supervision of nation-states. And (to go out on a limb here) it is perhaps one of Marxisms shortcomings as a practical political program that its foundational thinker underconceptualized the business corporation in his own works. (A key exception would be central banks such as the Bank of England and the Crdit Mobilier, about which Marx writes in great detail in his essays for the New York Tribune in these years.) A possible result is that his program has not always had the tools it needed to anticipate or reckon with the corporations growing puissance since the middle of the nineteenth century. Thomas Piketty, whose desire to follow and transcend Marx is expressed in the very title of his 2014 book Capital If part of the pleasure in reading Pikettys work comes from his willingness to use the feeling states evoked by a television series as evidence, part of the weakness of his analysis may be his underarticulation of the corporations that, since Marxs time, have played an increasingly large role in the economic system.

Where Marx, at least, is surely correct is in his recognition that we must use any such abstract term as