COLLATERAL DAMAGE

COLLATERAL DAMAGE

Women Write about War

Edited by Brbara Mujica

University of Virginia Press

Charlottesville and London

University of Virginia Press

2021 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia

All rights reserved

First published 2021

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mujica, Brbara Louise, editor.

Title: Collateral damage : women write about war / edited by Brbara Mujica.

Description: Charlottesville : University of Virginia Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020039749 (print) | LCCN 2020039750 (ebook) | ISBN 9780813945729 (hardcover ; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780813945736 (paperback ; acid-free paper) | ISBN 9780813945743 (ebook)

Subjects: LCHS : WarLiterary collections. | War and society. | LiteratureWomen authors. | Literature, Modern20th century.

Classification: LCC PN 6071. W 35 C 65 2021 (print) | LCC PN 6071. W 35 (ebook) | DDC 808.8/03581082dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020039749

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020039750

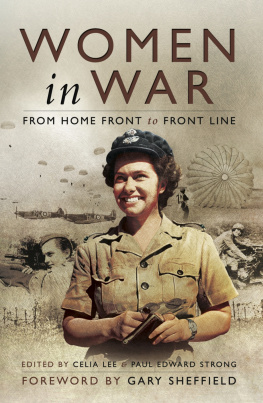

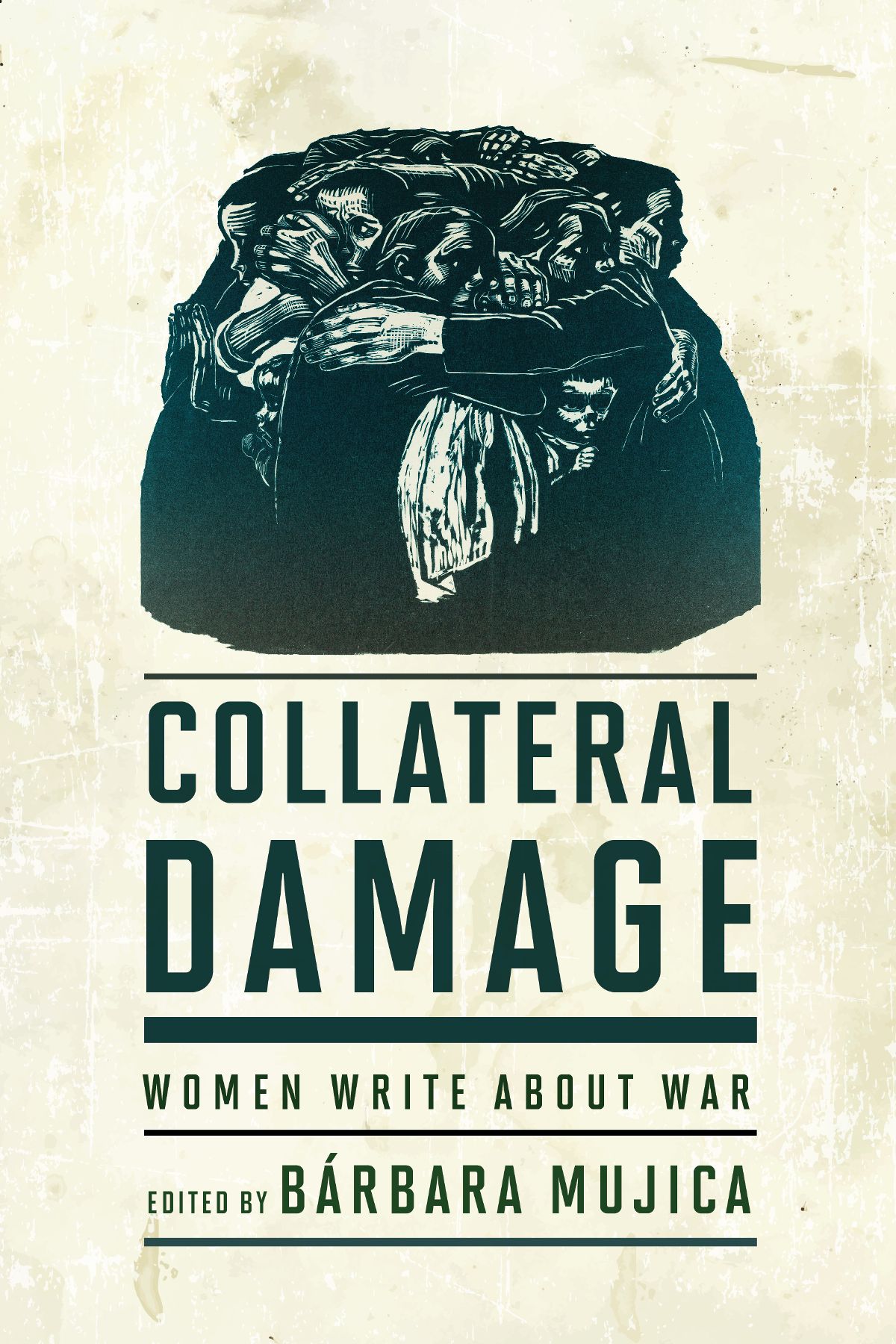

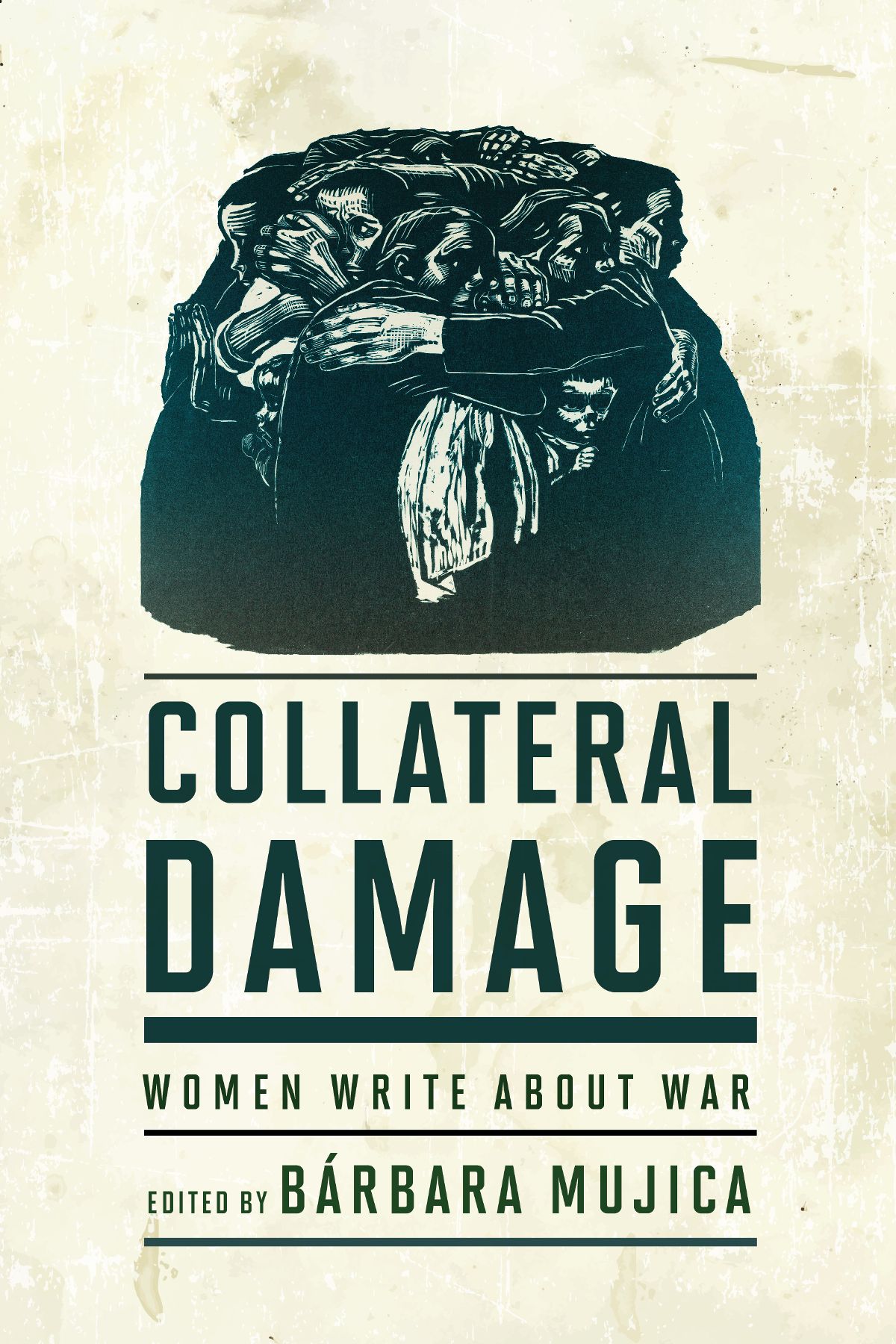

Cover art: Die Mtter (The Mothers), from Krieg (War), Kthe Kollwitz, 192122, published 1923. (Gift of the Arnhold family in memory of Sigrid Edwards; digital image The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

CONTENTS

The idea for this book originated in a symposium I organized in October 2016, at Georgetown University, called Women Who Write about War. At the time, I was faculty adviser of the Georgetown University Student Veterans Association and co-chair of the Veterans Support Team, a coalition of administrators, faculty, and students working to make Georgetown a more veteran-friendly campus. The veterans I worked with often told me stories, and I had begun writing fiction based on their testimonials. I noticed that many of my women friends who were authors also wrote about war, and I was interested in knowing why war was such a persistent topic in their writing.

With the help of LeNaya Hezel, director of our Veterans Office, I organized a panel of five authors from different countries: Marjorie Agosn (Chile), Christine Evans (Australia), Aminatta Forna (Sierra Leone), Domnica Radulescu (Romania), and myself (USA). The symposium was sponsored by seven university organizations. It was so well attended that we could hardly fit all the attendees into the room. The animated discussion that followed focused on the need to validate womens war experience and the value of womens war writing. Afterward, many in the audience encouraged me to compile an anthology of works by women who write about war. Collateral Damage is the outcome.

I would like to thank the following friends who suggested readings to help me prepare this book: Beth Simon, Billie Wilson, Susan Stern, Barbara Rappaport, Sami Al-Bani, Waleed Al-Ravi, Marty Thompson, Helmut Strey.

Whenever I tell people I am compiling an anthology of womens war writing, they always, without exception, answer in the same way: What? Do women write about war?

They must be forgiven for their mistake. Although the situation is changing, traditionally, men have fought wars, and men have produced our greatest war literature, highlighting the heroism, exhilaration, and pain of battle. Tolstoys War and Peace has been considered a manual of military art for its masterful depiction of combat. Novels by Hemingway, such as The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell to Arms, decry war as a destructive, senseless endeavor yet celebrate the battlefield as a proving ground for manhood. Even indisputably antiwar novels such as All Quiet on the Western Front, by Erich Maria Remarque, depict moments of beauty amid the violence: rays of moonlight shining on the manes of galloping warhorses, a meal shared with comrades amid bursting bombs. In literature as in life, war is seen as a rite of passage, a bond among men. It is not surprising, then, that people should think that only men write about war.

However, women and children have always suffered disproportionately the consequences of war: famine; disease; sexual abuse; and emotional trauma caused by the loss of loved ones, property, and means of subsistence. According to the International Peace Research Institute in Oslo, although men die more frequently than women in direct armed conflicts, more women than men die in post-conflict situations caused indirectly by war.

History does offer some notable examples of warrior womenSemiramis, Zenobia, the Adelitas of the Mexican Revolutionbut these are a minority. Of course, now that more women are moving into combat roles, increasing numbers are writing about their experience.

Collateral Damage tells the stories of those who struggle on the margins of armed conflict or who attempt to rebuild their lives after a war. It gives voice to the experiences of the mothers, sisters, friends, children, and victims of those who fight, as well as to a new type of war writer: the female combatant. It seeks to validate the experiences of women affected by war in different ways by bringing their reality to light and showing the actual consequences of war for millions of people whose voices are rarely heard.

Precedents: Women Writers of the Great Wars

Ancient examples of womens laments for sons or husbands departing for battle do exist, but war writing by women really began to blossom in the early twentieth century. Most early female-authored texts depicted women as bystanders, emotional and material casualties of wars fought by male loved ones. Who can forget, for example, the classic American novel Little Women, by Louisa May Alcott, which portrays the trials of the March sisters and their mother struggling to cope alone while their father is away during the Civil War?

The first real surge in womens war writing was inspired by World War I, which produced several outstanding women writers from a wide variety of countries. One of the most celebrated was the British novelist Rose Macaulay, whose witty, perceptive Non-Combatants and Others (1929) depicts a young woman, Alix, who becomes a pacifist after her brother dies at the front. In Missing, published in 1917, the British novelist Mary Augusta Ward chronicles the anguish of women who struggle to locate their husbands and sons reported missing during the war. In her memoir, The Home Front: A Mirror of Life in England during the World War, the British author Estelle Sylvia Pankhurst, a fiery suffragette and devoted Communist, recounts the struggles of working-class families in East London at a time when their menfolk were away at the front. Although Virginia Woolf did not write what might be properly labeled war novels, war is a significant theme in Mrs. Dalloway (1925), in which one of the characters, Septimus Warren Smith, is a veteran suffering from the illness we now call post-traumatic stress. Through this character, who grows estranged from his wife, hallucinates, and eventually commits suicide, Woolf examines the effects of war on soldiers and their loved ones.

The Great War also produced a number of poets and playwrights. Chicago-born Mary Borden moved to England with her Scottish husband in 1913. When war erupted, she used her fortune to set up a field hospital for French soldiers, where she herself served as a nurse. Her collection of short stories and poems, The Forbidden Zone (1929), reflects her firsthand experience at the front and was so graphic that many contemporary readers found it shocking. The Japanese poet Akiko Yosana began her career before World War I, during the Russo-Japanese War (19045). Her collection

Next page