Acknowledgments

The help of many made this work possible. This book began as a dissertation at the history department of Harvard University. For their guidance and support along the way, I would like to thank my dissertation advisers Ernest May, Akira Iriye, and Lizabeth Cohen. My other colleagues and friends at Harvard provided both inspiration and a critical, yet sympathetic, first audience for the projects ideas. I would especially like to thank Alexis Albion, Jonathan Conant, Brian Delay, Mark Haefele, Shigeo Hirano, Mike Makovsky, Wade Markel, Neal Rosendorf, Ryan Stanley, Ken Weisbrode, and Brad Zakarin. Two summer research grants from the Charles Warren Center of American History at Harvard University provided early support for this project.

I would also like to thank my teachers outside my graduate program. Felicia Pratto first taught me the joys and rigors of academic research. Barton J. Bernsteins teaching and scholarship provided an initial inspiration for this book. Frank Ninkovich gave crucial encouragement and advice early in the project and helped me to find a publisher at the end. The work of Michael Sherry and Paul Boyer served as intellectual and methodological models for this study. I owe a great many other intellectual debts for this work, and I have tried to acknowledge them adequately in my notes and bibliography.

For their help in facilitating my access to the archival materials that I needed for this project, I am grateful to the staffs at the National Archives, Truman Library, Eisenhower Library, Swarthmore Peace Collection, Naval Historical Center, Andover Harvard Theological Library, and Harvard Law School Special Collections. I would like to thank Charles Hanley for his generous help in sharing documents and his extensive knowledge of the 1950 killings of Korean refugees near No Gun Ri. The librarians at Widener Library, the New York Public Library, and Sterling Memorial Library helped me to track down relevant books and other materials. I would especially like to thank all the staff at Manuscripts and Archives in Yale Universitys Sterling Memorial Library who provided me with a friendly, stimulating, and supportive professional home while I was putting the finishing touches on this project.

My editor Kimberly Guinta and the staff at Routledge were a pleasure to work with, and I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on the manuscript. I am grateful to Dorothy Wells and Joel Rosenthal who helped lead me to Routledge. In addition, I would like to thank Blackwell Publishing, Inc. for granting me permission to republish material from Sahr Conway-Lanz, Beyond No Gun Ri: Refugees and the United States Military in the Korean War, Diplomatic History 29, no. 1 (January 2005): 4981 that appears in this work in altered form.

I could not have seen this work to completion without the love and support of my family. Dolores believed in me and my ideas, and she has brought countless joys into my life. My parents were my first teachers, and I could not have asked for better ones.

1

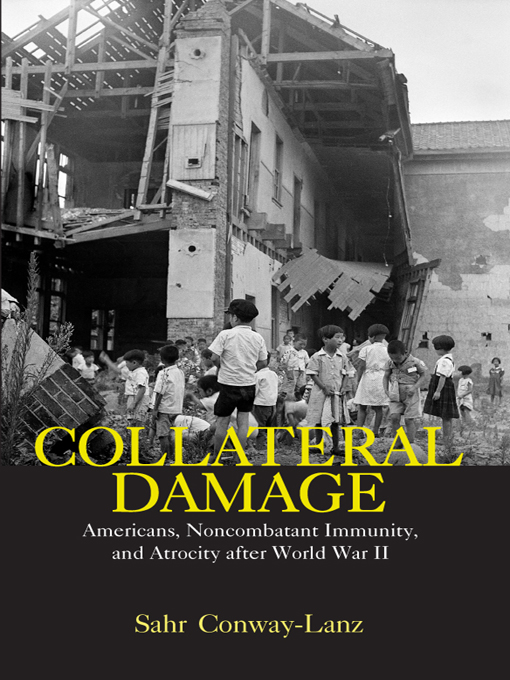

Modern War and Mass Killing

On the night of March 9, 1945, more than 250 American B-29 bombers arrived over Tokyo. Each plane carried about six tons of bombs, most filled with a new chemical incendiary called napalm. Dropped in a precise pattern on the city, the fire bombs ignited the largest human-made conflagration ever used as a weapon in war. The bombs fell on a twelve-square-mile rectangle of one of the most densely built-up residential districts in the world, home to more than 1.2 million people. Strong winds whipped the scattered fires ignited by the bombs into a raging firestorm that engulfed entire neighborhoods. The citys residents died by the thousands. When the firestorm subsided more than nine hours later, it had burned out almost sixteen square miles of Tokyo. The destruction was greater than that which the first atomic bombing would inflict on Hiroshima three months later. Tokyo police recorded 267,171 buildings destroyed, leaving more than one million people homeless. Japanese and American officials placed the casualty toll at 83,793 dead and 40,918 wounded. With many schoolchildren evacuated from the city and young men away serving in the military, women, babies, and older men were most of the victims.

The burning of Tokyo was part of a larger campaign of destruction against Japan and Germany in 1945 that the Allies used to help hasten the end of World War II. The British had conducted the first large-scale fire bombing against Hamburg in 1943, which destroyed much of the city and killed an estimated 44,000 people. In early 1945, American planes joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in showering Dresden with incendiary bombs that ignited another city-devouring firestorm. The incineration of Tokyo began a five month campaign conducted by the U.S. military to burn most of Japans major cities to the ground. The destruction reached a final climax in August 1945 when American bombers dropped the first atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The incendiary campaign against Japan devastated 180 square miles of 67 cities, and the entire American strategic bombing effort killed more than 300,000 Japanese and injured an additional 400,000. Most of the victims were civilians.

Killing so many civilians and destroying so much in such a short time was unprecedented in warfare, and this capacity for massive destruction provoked growing concern about the violence of war as Americans became increasingly aware of what their armed forces had done. U.S. weapons, like never before, could inflict death and destruction over wide areas, but this capability made the violence difficult to control. Often times, the weapons did not allow for discrimination between their victims. In the war, American arms had killed women, children, the elderlynoncombatants posing little immediate threat to their attackers. Such harm violated the long-standing and widespread international norm of protecting the innocent from arbitrary injury in war. Western theologians and moralists have called this protection noncombatant immunity and the destructiveness of the Second World War proved to be one of the greatest challenges that the norm had ever faced.

The contradiction between new massively destructive methods of warfare and noncombatant immunity was made more acute in 1945 because the world had begun to learn the full extent of the killings carried out under the Nazi regime. With the revelations of Nazi genocide, peoples around the world had a fresh and horrific example of the slaughter of civilians. The Holocaust would emerge as the epitome of inhumane atrocity in the twentieth century. Some, including Americans, saw unsettling similarities between American methods of warfare in the bombing campaigns of 1945 and the German atrocities. Both killed the innocent arbitrarily. The victims were innocent in the sense that they posed little direct threat to their assailants and were arbitrarily killed in that the victims died because of their nationality, creed, or simple geographic location and not specifically because of any actions they had taken or hostilities they had held against their killers.

The contradiction between new methods of war and noncombatant immunity and the resemblance, even if vague, between American and Nazi actions proved unsettling to many Americans and others in the shadow of U.S. military power. These developments disturbed Americans perceptions of themselves as a humane people. They also jeopardized the United States international reputation as a humane nation, an image that American leaders hoped could help forge a coalition in the emerging Cold War. However, the dilemma was more than a question of American image and identity. Because of American international influence buttressed by its military might and possession of nuclear weapons, how the United States dealt with the contradiction had far-reaching implications for the world.