CLINT EASTWOOD

AND ISSUES OF AMERICAN MASCULINITY

CLINT EASTWOOD

AND ISSUES OF AMERICAN MASCULINITY

DRUCILLA CORNELL

Copyright 2009 Fordham University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

The final, definitive version of .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cornell, Drucilla.

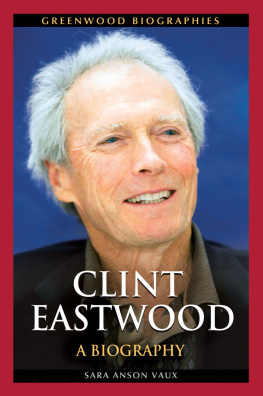

Clint Eastwood and issues of American masculinity / Drucilla Cornell.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Includes filmography.

ISBN 978-0-8232-3012-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8232-3013-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Eastwood, Clint, 1930 Criticism and interpretation. 2. Masculinity in motion pictures. I. Title.

PN1998.3.E325C67 2009

791.430233092dc22

2009002461

Printed in the United States of America

11 10 09 5 4 3 2 1

First edition

Contents

Preface

As for so many of my generation, Clint Eastwood was simply a part of the social landscape in which I grew up. My ex-husband met him on the set of Rawhide, and my mother campaigned for him when he ran for mayor of Carmel, California. My father, like so many of his Republican cohorts, simply idolized Eastwoodhe was their man. Still, I never really paid much attention to him, because he was part of a landscape that I thought I had long outgrown as a feminist. Indeed, my first opportunity for serious engagement with Eastwoods work as a director came only a few years ago during a visit with my father in Laguna Beach, where the small movie theatre was playing only two films, one of which was Eastwoods Mystic River. My father surprised me by warning me to avoid the film, commenting that something bad must have happened to Eastwoodhe claimed Mystic River was the worst film he had seen since Closely Watched Trains, a film that I had dragged him to see when I was nineteen. He said that Eastwood seemed to be making some point about men, but dismissively he confessed that he had no idea what it was supposed to mean. Naturally, I immediately went off to see the filmand I agreed wholeheartedly that Eastwood was, indeed, addressing some of the most profound questions of American masculinity. But unlike my father, I thought I got the point.

The very man who seemed to be such a disappointment to my father had become to my mind one of those rare men who actually struggle with what it means to be a good man at a time when all the props that held up ideals of masculine goodness had fallen into disarray. Eastwood This book, I want to stress, is not focused on Eastwoods personal journey as a man, nor as he was produced as a cultural icon nor on the specificity of his acting style. I have a different project, which is to study Eastwood as a director as he is relevant to certain major philosophical and ethical themes that I have personally articulated throughout my lifes work. The particular tenure of this project compels me to take up all of what I consider to be the pressing issues of masculinity as it is caught up in the very definition of ideas of revenge, violence, moral repair, and justice. Eastwood grapples with this involvement of masculinity in and through many of the great symbols of American life, including cowboys, boxing, police dramas, and ultimately warperhaps the single greatest symbol of what it means (or is supposed to mean) to be a man.

Thus, I still have hope that my father may actually read this book and that it may take him to a deeper appreciation of Eastwoods work as a director as well as the dilemmas facing any aspiration to ethical manhood. Indeed, I am hoping that this book will be widely read by men, perhaps more widely read than some of my other feminist work. Masculinity has recently become a very popular and important topic for social critics, and I have long wanted to address some of these issues myself. But when I tried to think about writing on masculinity in general, I felt lost in a project too large for myselfand so, having written with Roger Berkowitz on Mystic River, I decided to undertake a smaller project that nevertheless provides me with the space for at least preliminary reflection on almost all of the great symbols of American masculinity. If I could not write about all men, maybe I could handle just one.

This book, then, is not a traditional book of film criticism or a cinematographic biography; neither is it Eastwoods unauthorized biography. As a work of social commentary and ethical philosophy, it is inspired in large part by the work of my late colleague Wilson Carey McWilliams, who turned his brilliant analysis of American political thought primarily toward the world of literature, arguing that it has always been in our cultural products that Americans express our greatest political ideals and concepts. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, of course, the new medium of film has clearly dominated the scene of artistic cultural production.

Eastwood takes us through some of the great images and symbols of American life through his engagement with classically American film genres from cowboy movies to police thrillers to boxing heroics. In a world in which we seem to be losing our grasp on shared symbols along with community itself, Eastwoods films work with those fragmented symbols that remain in order to engage masculinity with the most profound moral and ethical issues facing us today. Over and over again he returns us to that simple question: what does it mean to live a life as a good man in a complex and violent world? I concede that much is to be said for the broad literature that has criticized the idea of the director as auteur, the originator and sole author of the images and narrative line of his films. However, although Hollywood imposes real limits on what will be allowed to reach the screen, through all my work I have argued against a theory of the subject that pretends to tell us exactly how we are limited and constituted so that, underneath it all, we cannot find even a remnant of the subject who creates. Indeed, if one wished to put this idea of the subject that is irreducible to any theory of it as constituted as a social object or, in Eastwoods case, a cultural object, we could be reminded here of Jacques Derridas endless emphasis on the iterability of all linguistic and symbolic forms, including those which both limit and allow a range of subjective agency. This insight into the inevitable iterability of linguistic and symbolic forms even as they are repeated to give us a meaningful world could be used in two ways to understand my own insistence that it is possible to study Eastwood as a director. First, there could be no theory of the subject that so encompasses Eastwood as a cultural production that all of his agency as a director is simply eclipsed. Second, genres are indeed symbolic as well as cinematic forms, and it is precisely Eastwoods subtlety in reworking these forms (while seemingly repeating them) that shows the power of iteration to break up as well as to ground the bounds of meaning. Whatever other factors may have contributed to his films, there is no doubt that Eastwoods interests and choices have stamped his work with a distinctive trajectory that builds upon, disrupts, and reenvisions the very masculine stereotype for which he is known so well. Indeed, what makes Eastwoods work so interesting is how he engages with accepted genres and pushes them to their limits.

Next page