Miek Zwamborn - Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany

Here you can read online Miek Zwamborn - Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: GreyStone, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany

- Author:

- Publisher:GreyStone

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

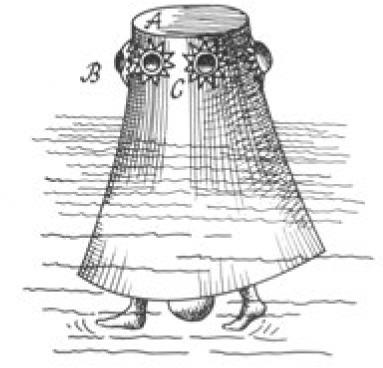

Diving bell invented by Franz Keler, around 1600.

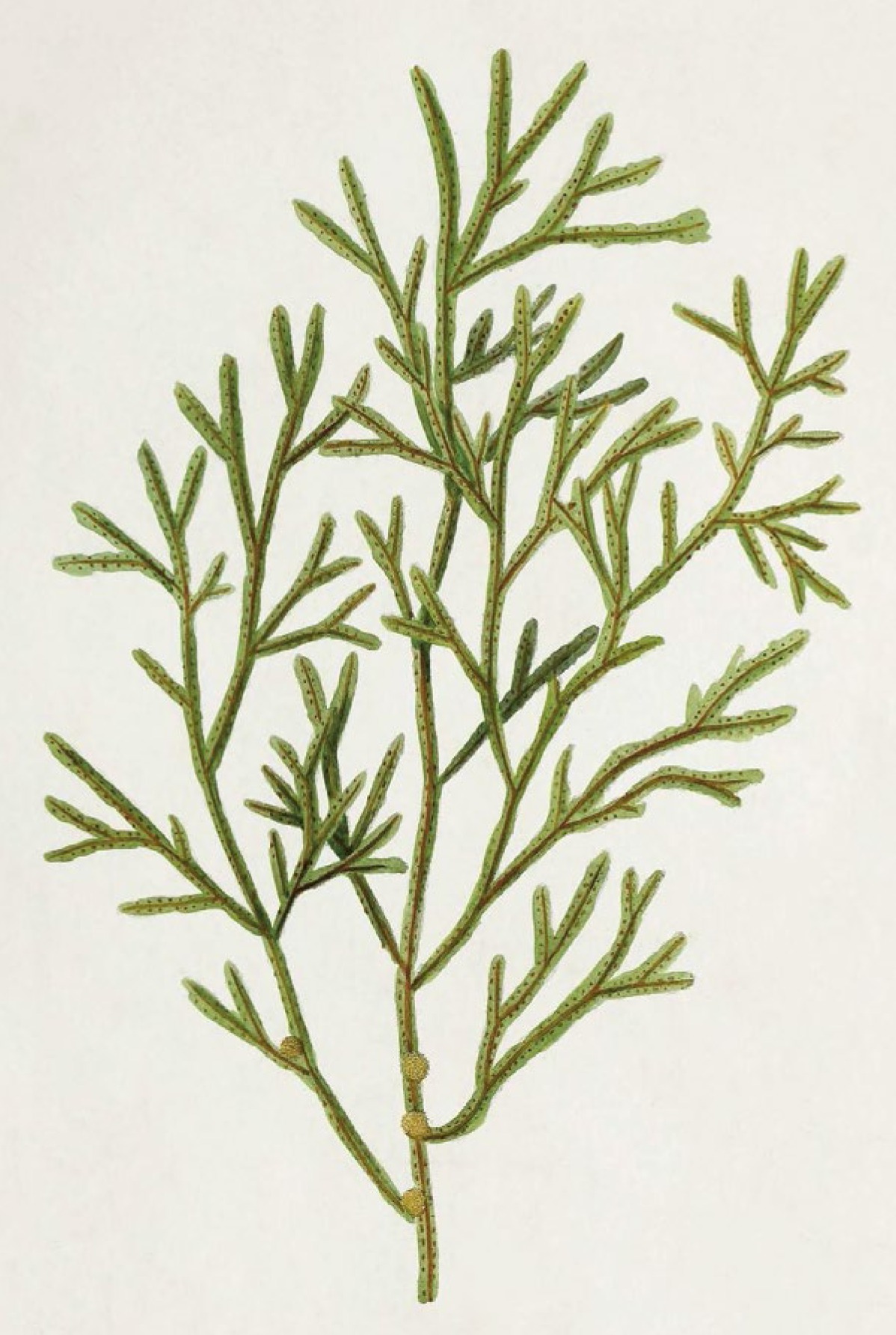

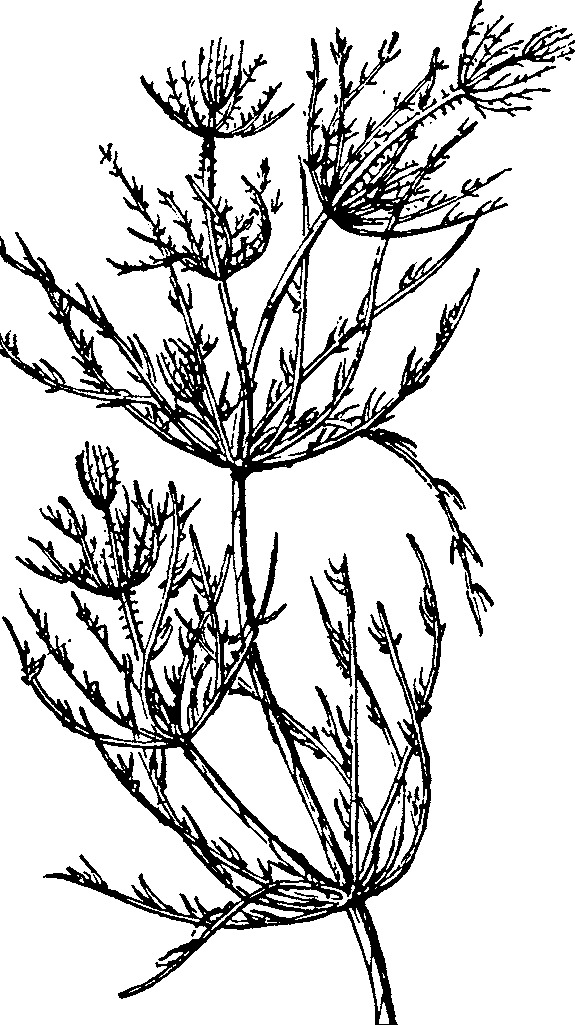

Fucus vesiculosus from Hydrophytologiae Regni Neapolitani icones, Neapoli 1829.

At first I saw everything from below, and then I was algae.

MONIKA RINCK

The fronds of Nitophyllum smithii rise up like a blazing fire. Joseph Dalton Hooker picked this specimen during his Arctic expedition in 1842 in the icy sea around the Falkland Islands from the holdfast of a larger seaweed.

Contents

Underwater Forests

WALKING TO THE SCOTTISH TIDAL ISLAND of Erraid at ebbtide, I came across an immense chunk of seaweed beached in the bay. Its dark leaves and stems contrasted strongly with the pale sand. The seaweed looked lively and spiralled like an Archimedean screw. The outgoing tide had tugged the leaves open wide. A sturdy stem emerged from a large gold-studded ball; not round but flat and wide, bordered with amber-coloured ruffles. The stem became smoother as it progressed and ended in a leathery leaf that was split into 21 long, ragged strips, each pointing in a different direction. My gaze slid back along the milled edges of the stem. The seaweed plant shone as though it had been polished and seemed to be filled with a strange force. It appeared boundless. Although torn from its colony and washed ashore, it showed no signs of decay. I kneeled down and ran my fingers through the strands. The stalk and leaves felt firm and were cooler than I expected.

Of course I had seen seaweed before, at home growing up in the Netherlands. I had slithered over it to reach the mudflats beyond the dyke. I had folded it back over rocks to fish for shrimp and covered my oysters with it after collecting them in a bucket. It sometimes wrapped itself around your legs in the sea. Yet I had never really looked at it properly. The mysterious appearance of this specimen, which had grown under water into such a coquettish beauty, changed that. I am not exaggerating when I say that it brought about an immense shift in my experience of the coast. The sea had opened up to me that day and, before the tide turned, Id been allowed my first peek inside.

With its flamboyant ruffles along the thallus, Saccorhiza polyschides is one of the most sensuous seaweeds.

I carefully slid my hands under the heavy stem and stood up. The weed heeled over, forming a parabola. I slung it over my shoulder. It was twice my height. Folded double it touched the rippled sand on both sides: a vertical embrace. Zigzagging around the bronze-green bladderwrack that covered the rocks in the bay, I headed across the mudflats to Erraid. When I looked back at the beach where I had come from, I saw a winding line next to my footprints. The ends of the leaves were heavy enough to trace our route in the sand.

Perhaps it was because, in my work as an artist, I had been compiling the absolute opposite for a while: a herbarium, a collection of mounted dried plants, in which the green foliage was brittle, pale and motionless, affixed to the page with tiny stitches. This clump of seaweed, on the other hand, was brimming with life. It excelled in elasticity and tenacity. The robust texture and baroque elegance lent it something alien. How could the cells of a simple organism grow into such exuberantly complex matter? The discovery of the seaweed giant sparked in me an urge to explore the seas depths.

I had brought seaweed onto dry land, an individual specimen that had reached a respectable size on its own. In the days that followed I collected nothing but seaweed: green, red and brown varieties and all the colours that lie between them; and spotted, perforated, translucent, albino. I cut it loose from the rocks, plucked it from the surf or picked it up along the tideline. I submerged shrivelled seaweed under water until it unfolded and revived like roses of Jericho. This was how it began.

Seaweed is the collective name for marine algae, which divide into macroalgae and MICROALGAE. Macroalgae are the most flexible, resilient and fertile plant species on Earth. They can survive on the rugged and turbulent coastlines of the most unstable environments and can be found in all climate zones, from the tropics to the poles. There are around 10,000 different species, some of which survive in extremely harsh conditions, enduring storms, penetrating sunlight, acidification and drying out at low tide. Fossil records indicate that seaweeds have been in existence for 1.7 billion years. They seem to have evolved little in all this time.

Within the plant kingdom, algae are classified as lower plants. They have no structures that characterize the more sophisticated, higher plant types: no roots, stems, leaves or conductive tissue. Each individual cell within a seaweed plant is able to provide for itself, independently of the other cells in the plant.

Seaweeds nourish themselves by photosynthesis. Like the higher plants, they contain chlorophyll, but the pigments that absorb the sunlight are variable. Seaweeds can be green, but also red, brown, yellow or orange, due to the fact that the green pigment can be masked by other pigments.

Most seaweed can be subdivided into six main groups based on colour, structure and lifecycle.

GREEN SEAWEEDS are single or multi-celled green-coloured algae. The single-celled species often have two whip-like strands (flagella) of the same length, anchored in the cell body, which allow them to propel themselves through the water. Multi-cellular species can take the most varied forms. Green algae have the same type of chlorophyll as land plants. Green algae are mainly found in fresh water. However, some also thrive in salt water. It is assumed that they share common ancestors and that land plants evolved from green algae.

Many weeds grow as epiphytes on other algae and flutter loosely in the current.

RED SEAWEEDS are multi-cellular red-coloured algae, but there are also single-celled types. They mainly live in the sea, but some species occur in fresh water or on land. They are usually branched, some have leaf-like fronds, others have chalky crusts. Chalky red seaweed stores calcium deposits and, as a result, makes an important contribution to the formation and stabilization of coral reefs.

BROWN SEAWEEDS are multi-celled, brown-coloured algae with a complex construction. They are often branched, with leaf- and stem-shaped structures. Brown algae are almost exclusively found in the sea. This group includes the largest and fastest-growing seaweeds on Earth, such as the giant kelp, which grows into immense kelp forests.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany»

Look at similar books to Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Seaweed, an Enchanting Miscellany and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.