Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For all the women warriorspast, present, and future

A nation is not conquered until the hearts of its women are on the ground.

CHEYENNE PROVERB

In the end, all books are collaborative ventures and this one is no exception. It benefited immensely from a diligent army of people who collectively blended their diverse talents, focus, and energy to make this book possible. My gratitude goes to researchers extraordinaire Kaci Nash, with the University of Nebraska Center for Great Plains Studies; Donzella Maupin and Andreese Scott, with Hampton University Archives; and librarian Steve Rice at the Connecticut State Library. To friends and colleagues Tim Anderson, Kathy Christensen, and Monica Norby, whose good ears, instincts, and common sense kept the narrative on track. To Patricia Lombardi, whose patient listening on cold winter days and incisive comments afterward improved the manuscript in ways both large and small. To Astrid Munn, whose initial research and concise, timely summaries proved invaluable, and John Mangan, for his extensive knowledge of Omaha Reservation geography. To Jane Johnson, Margaret Johnson, Carolyn Johnson, Kathleen Diddock, and Chris Conndirect La Flesche family descendants whose cooperation and generosity never ended. To Vida Stabler, Lisa Drum, and Taylor Keencitizens of the Omaha Nation with a vast knowledge of tribal history, culture, and traditions. To Judi gaiashkibos, a special friend whose numerous suggestions and wise counsel were always on the money.

To agent Jonathan Lyons, for his passionate encouragement in the early going, and to editor Daniela Rapp at St. Martins Press, for her steady hand and superb editorial suggestions in the later stages.

Finally, there are three people whose contributions to this project can hardly be overstated. John Wunder, an eminent historian specializing in the American West, did his part to maintain balance, perspective, and accuracy throughout the narrative. Christine Lesiak, whose documentary on the same subject unfolded at the same time as the book, wasand isa constant source of inspiration. And without the unflagging energy, sharp eye, day-to-day dedication, and overall talents of Roger Holmes, this story would have been greatly diminished.

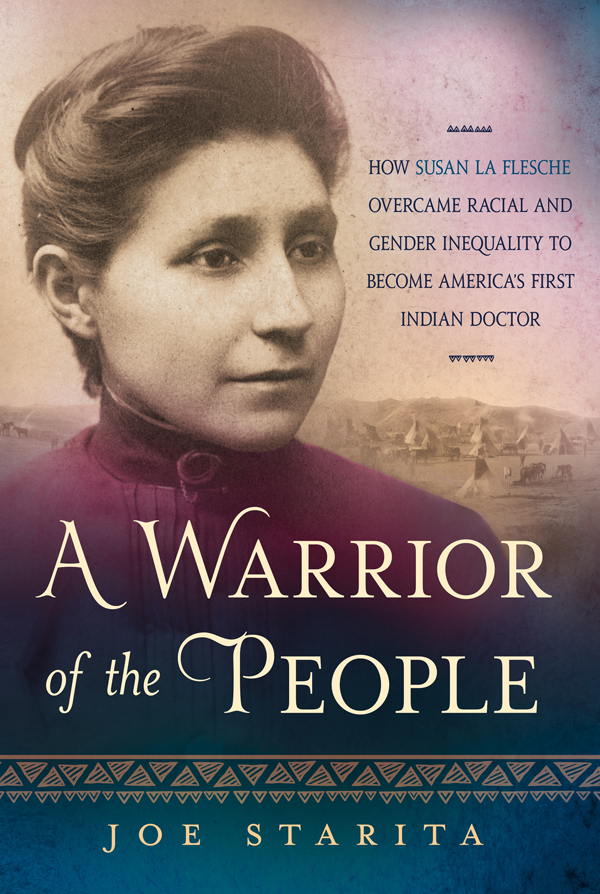

Throughout this story, I have tried to capture Susan La Flesche in all her emotional and human complexityfrom the innocent joy of childhood, the devotion to her father, and the anxiety of leaving behind a beloved homeland for a New Jersey boarding school to the crushing loss of an early love, the stress of medical school, the fear of dying alone an old maid, the anxiety of searching for a desperately sick girl on the frozen prairie, and the pain of coping with a husbands death.

In a number of instances, her inner thoughts, her point of view, and what she was thinking and feeling at certain moments are all woven into the narrative, often without direct attribution.

These moments when Susans inner thoughts and private reflections occur in the story are all distilled from an exhaustive examination of the treasure trove of primary source documents she left behind. Specifically, her private thoughts and feelings derive directly from hundreds of pages of her personal diary, scores of richly detailed letters to family and friends, and transcripts from the many editorials she wrote and speeches she gave.

For example, in graduation remarks she gave at Hampton, Virginia, in 1892a speech entitled My Work as Physician Among my PeopleSusan gave an exceptionally detailed account of her search for and treatment of a fourteen-year-old girl dying of tuberculosis. In the narrative, I borrow heavily from her speech in reconstructing this scene, but I do not cite it in the text so as not to interrupt the narrative flow. It is, however, cited in the endnotes section of this book and in the bibliography, along with all other documents used as the building blocks for this story.

Taken collectively over the arc of her life, these documents provide a rich, intimate, fact-based portrait of a complex woman who often revealed herself in the full light of what it means to be human.

Its five A.M. on a midwinter morning, the mercury stuck at twenty below. Overhead, a canopy of constellations spills across the clean winter sky, the quarter moon a slim lantern hanging above the vast, black, desolate prairie.

Shes walking to the barn, through the snow, layered in muffs, mittens, and scarves. Still, her ears are numb, her face frozen, her breathing labored.

She steps inside the barn, carefully placing a small black bag on the buggy seat. For a time, if it were less than a mile, she would just walk. Then she took to slinging the black leather bag across her saddle, making house calls on horseback. But bouncing across the rugged terrain took its toll on the glass bottles and instruments, so she eventually bought a buggy, bought her own team.

Inside, her two favorite horses wait impatiently, snorting thick clouds of steam into the ice-locker air. She grabs their harness, hitches them to the buggy, guides them out of the barn. Then she climbs in and gets her chocolate mares, Pat and Pudge, heading in the right direction, their ghostly white vapor trails hanging in the frigid blackness.

Its early January 1892, a month her people call When the Snow Drifts into the Tents. The woman in the buggy, the one lashing her team to move faster, is a small, frail twenty-six-year-old, a devout Christian who also knows her peoples traditional songs, dances, customs, and language, a woman who just recently acquired 1,244 patients scattered across 1,350 square miles of open prairie now blanketed in two feet of snowa homeland of sloping hills, rolling ranch land, gullies, ravines, wooded creek banks, floodplains, and few roads.

The air crushes her face, stings her ears. She pulls a thick buffalo robe over her shoulders to buffer the subzero winds, lashing the horses flanks again and again until the buggy picks up the pace, its wheels moving over one ridge and then another, through deep drifts covering the remote hillsides of northeast Nebraska.

In the darkness they keep moving, keep going, and all the while, over and over, her mind keeps drifting to the same recurring thought:

Can I find her?

Will I get there in time?

* * *

They were known as the Omaha Umo n ho n . In the language of her people, it meant against the current or upstream, and their Sacred Legend, their creation story, said the Omaha had emerged long ago from a region far to the east, a region of dense woods and great bodies of water.

In the beginning the people were in water. They opened their eyes but they could see nothing. As they came forth from the water they were naked and without shame.

In the beginning, in their eastern homeland near the Ohio River, the Omaha encountered many problems. Having emerged naked from the water, they were cold and wet and hungry, and someticulously and methodicallythey began to look for solutions, and by and by, they found them: clothing, fire, stone knives, arrows, iron, dogs. Over time, they emerged as a practical people, a people who craved progress, who time and time again looked to conquer hardship and inconvenience with a straightforward determination, with their own ingenuity and technological innovations.