A people without a history

is like wind on the buffalo grass.

CRAZY HORSE, OGLALA SIOUX

Acknowledgments

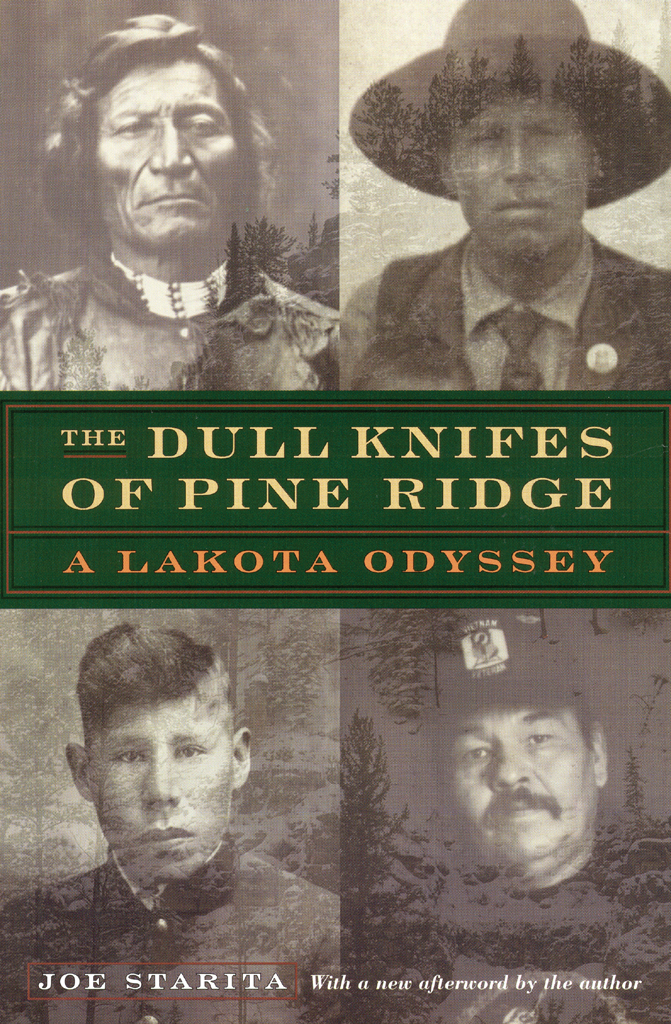

Many thanks are in order to the large numbers of people who contributed to this project. To Phil Krous, Judy Barker, Margaret Odgers, June Levine, Dan Ladely, Ben Gregory, Pat McLaughlin, Rich Lombardi, Bill and Kathy Steinke, Woody and Georgia Garnsey, Jim Starita, Judi Olivetti and Melissa Malkovich, whose friendship, good judgment and common sense helped keep the manuscript on course. To David Wishart, whose grasp of the subject matter and thorough reading of the text were invaluable. To Carl Hiaasen, Doug Clifton and Fred Grimm, friends and Miami Herald colleagues, who shared suggestions and encouragement from beginning to end. To Richard Ovelmen and Edward Soto, who provided documents and advice. To Jaime Obrecht and Bill Bowman, Vietnam veterans who knew the difference between a trenching tool and an entrenching tool, and a lot more. To photographers Ted Kirk and Bob Fader, whose technical skills spanned old photos and new and everything in between. To John Carter and the staff of the Nebraska State Historical Society, for their diligence in providing access to a vast array of photographs, microfilm, books and documents, frequently on short notice. To Tom Buecker, curator of the Fort Robinson Museum, for his superb knowledge of a place and time, and to the staff of the Sierra Vista Health Care Center, for their patience. To Ellen Allen, Custodian of Records at the Haskell Indian Junior College. To will Norton and Michael Stricklin, at the University of Nebraska Graduate School of Journalism, for their support, and to the Hitchcock Center, for its generous Fellowship. To agents Steve Delsohn, Frank Weimann and Jessica Wainwright, who made things happen, and to editor Neil Nyren, at G. P. Putnams Sons, whose steady hand kept it moving.

A special thanks for the two people whose importance to the project would be impossible to overstate: To Roger Holmes and Emily Levine, whose dedication, determination, and desire to get things right never wavered.

Finally, there is a heartfelt gratitude to the Lakota people. To Marcella Gilbert and her mother, Madonna, who was inside the village at Wounded Knee, and to Charles Trimble, whose brother, Al, spent a lifetime working for the best interests of the Oglala Sioux. To Charlotte Black Elk, Royal Bull Bear, Leonard Yellow Elk, Mel Lone Hill, Sam Loud Hawk and Richard Moves Camp, the people from the land who have endured forever and kept the traditions alive for the children.

And most of all, to the Dull Knifes of Pine Ridge, to the old man in the nursing home and his son and his son, to Nellie and Cora Yellow Elk, who for two years, graciously and patiently, answered questions and told the stories in tents and tipis, in cars and vans, at breakfast, lunch and dinner, in summer and winter, in the Black Hills and Rockies and on the shortgrass prairies of South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming and Colorado. Mitakuya-owasin.

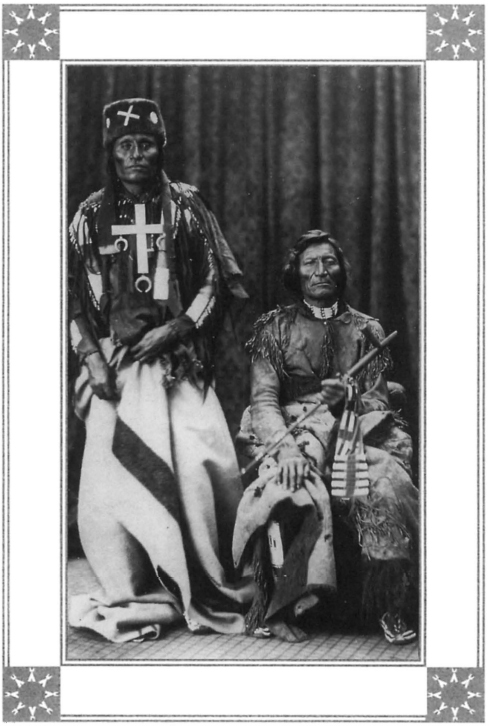

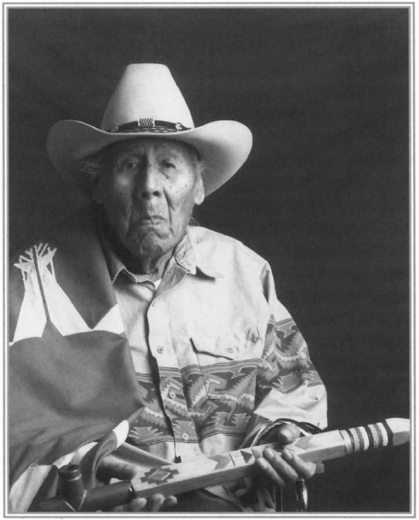

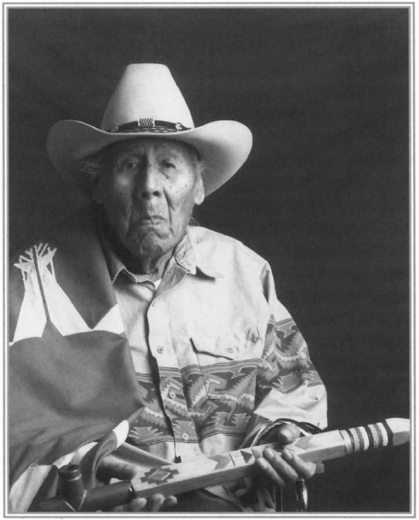

Guy Dull Knife Sr.

(B OB F ADER )

Chapter One

The Old Man in the Nursing Home

She doesnt quite know what to make of the old man sitting beside her.

Slowly and gently, he is speaking to her in the language of her people, but she is just learning English and so his words have no meaning for her.

Waste. Wicincala Waste.

They are side by side, maybe a foot apart. Her tiny LA Gear sneakers barely creep over the edge of an olive army blanket spread across the nursing-home bed. She keeps looking at the old man and then over at the family across the room, her mouth wide open, her head shifting back and forth as if at a tennis match, her eyes searching for some sign that she is safe. She seems continually on the verge of rolling over on her stomach, sliding down the bed and running to the others, but right now she is too afraid to move, so she sits stock-still staring at the old mans face, at the black eyes, the high, flaring cheekbones, at the great hawk nose. Years ago, he stood six-feet-five and weighed three hundred pounds. Even now, she is dwarfed by his broad shoulders and thick chest. He is wearing a beige felt cowboy hat with an eagle feather stuck in the brim. His iron-gray hair, pulled neatly in a ponytail, hangs to the middle of his back.

Almost a century stands between his birth and hers and so he doesnt really know too much about the little great-granddaughter; knows nothing of her fascination with deep-dish pizza and Lego building blocks or the music videos she watched a few hours before the family arrived.

And she doesnt know much about the old man who is trying to make her smile with the funny-sounding words. She doesnt know of his old friend and neighbor, and the young lieutenant that friend saw coming through the dust and smoke on the east side of the Little Bighorn that afternoon. She knows nothing of his grandfather, the dignified chief and trusted statesman who had counseled peace, who cowered in the snow at the end, waiting for the soldiers, eating his moccasins to survive the last few nights.

She has yet to hear the stories the old mans father told him about the ride to the hill above Wounded Knee Creek after the shooting stopped; the lean years when he was a young boy in charge of feeding eleven brothers and sisters while his father was in Europe with Buffalo Bill.

Nor the stories of the mud and rain and mustard gas, of squatting in the trenches day after day, and how, when it was finally over, this old man, sitting now on the edge of the bed in a Colorado nursing home, couldnt vote in his homeland because the government that had sent him to the Great War did not consider him an American citizen.