Books by Mari Sandoz published by the University of Nebraska Press

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Beaver Men: Spearheads of Empire

The Buffalo Hunters: The Story of the Hide Men

Capital City

The Cattlemen: From the Rio Grande across the Far Marias

Cheyenne Autumn

The Christmas of the Phonograph Records

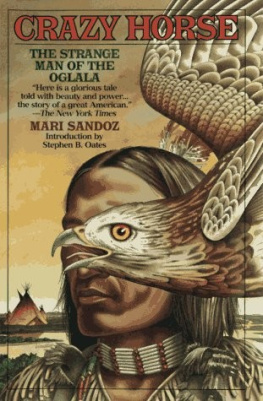

Crazy Horse: The Strange Man of the Oglalas

The Horsecatcher

Hostiles and Friendlies: Selected Short Writings of Mari Sandoz

Letters of Mari Sandoz

Love Song to the Plains

Miss Morissa: Doctor of the Gold Trail

Old Jules

Old Jules Country

Sandhill Sundays and Other Recollections

Slogum House

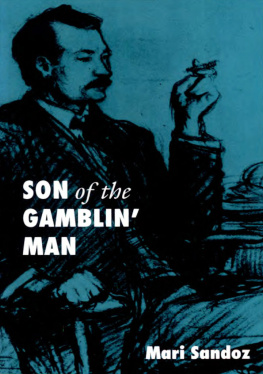

Son of the Gamblin Man: The Youth of an Artist

The Story Catcher

These Were the Sioux

The Tom-Walker

Winter Thunder

CHEYENNE AUTUMN

BY MARI SANDOZ

Introduction to the Bison Books Edition by Alan Boye

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS LINCOLN

1953 by Mari Sandoz

Introduction 2005 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Reprinted by arrangement with the Estate of Mari Sandoz, represented by McIntosh and Otis, Inc.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sandoz, Mari, 18961966.

Cheyenne autumn/Mari Sandoz; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Alan Boye.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: McGraw-Hill, 1953.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-9341-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8032-9341-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-9373-1 (electronic: e-pub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-9374-8 (electronic: mobi)

1. Cheyenne IndiansKings and rulersBiography. 2. Cheyenne IndiansHistory. 3. Cheyenne IndiansGovernment relations. I. Title.

E99.C53S2 2005

978.004'97353dc22 2005009164

Contents

ALAN BOYE

Introduction

Under cover of darkness on the night of September 9, 1878, a band of Northern Cheyenne Indians fled U.S. Government captivity in Oklahoma to begin a bitter and tragic but ultimately triumphant journey to their Montana homeland. That night about three hundred men, women, and children were able to slip away from their standing shelters so silently that one hundred soldiers camped nearby and positioned to prevent their escape from Indian Territory continued to sleep, unaware. For the next several months these Cheyennes struggled northward toward their ancestral lands, all the while evading capture and engaging the military in several battles.

The bloody century of war with the Native peoples of the West was reaching its climax. Only two years earlier many of these same Cheyennes had helped wipe out George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Since then the U.S. Government had been conducting an all-out offensive against Indians of the northern plains. As a part of this campaign, a Northern Cheyenne villagelocated in what is now Wyominghad been destroyed in a surprise attack during the winter of 1876. More than a thousand people abandoned their belongings and fled into the mountains with nothing more than the clothes on their backs.

The following spring, destitute and on the brink of starvation, these same Northern Cheyenne people agreed to be taken south to Indian Territory, with the understanding that they would be able to return to their northern homelands if they did not like it there. Once they arrived in the south, however, their misery only worsened. They were forced to compete with their southern cousins for each bite of government-issued beef. Malaria, whooping cough, and measles killed their children. Deprivation was everywhere. After suffering for a year, the Northern Cheyenne people said they were going to return to their homeland in the north as they had been told they could. The U.S. Government refused to let them go, and instead had them watched day and night.

The Cheyennes left anyway.

Under the leadership of a brilliant warrior named Little Wolf, and guided by the wisdom of an old chief named Morning Star (or Dull Knife), the Indians fought a thousand-mile running battle in order to regain their homeland. Before it ended, tens of thousands of U.S. Army troops were called in to help search for the small band of Cheyennes.

While in Nebraska the band separated into two groups. Roughly half of the refugees, including Dull Knife, Wild Hog, and other leaders, were apprehended in late October when, blinded by a snowstorm, they stumbled upon a group of soldiers. The soldiers disarmed the Cheyennes and then marched them to imprisonment at a military post at the southern edge of the Dakota Badlands. Held in a room roughly the size of a basketball court, the 149 refugees spent the next six weeks in relative comfort, untilthanks to bureaucratic squabbling and inadequate leadershipthe government ordered them to return to the south.

The Cheyennes refused to go. They said they preferred to die in their homeland rather than return to the sickness and misery they had known in captivity. The doors and the windows of the building were sealed shut; first the food was taken away, then the water. A few days later, on the bitterly cold night of January 9, 1879, the Cheyennes smashed their way out of the building. Within moments dozens of men, women, and children were dead or wounded from soldiers gunfire. The rest escaped into the nearby hills. After being trailed for weeks, almost all of them were slaughtered in a shallow pit not far from the South Dakota border.

Little Wolf and the other half of the Cheyennes evaded capture. They spent the winter hiding out in northwestern Nebraska before making their way northward in the spring. They made it to Montana, where eventually they were given a small reservation in the southeast corner of the state. This reservation today continues as the home of the Northern Cheyenne people.

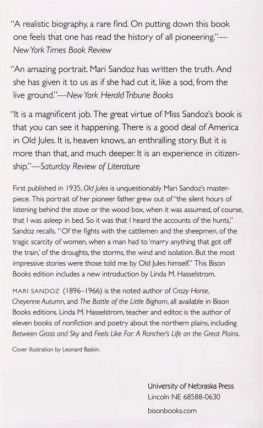

The most masterful and authentic retelling of the Cheyenne exodus is Mari Sandozs Cheyenne Autumn. Intimate, lyrical, and moving, Sandozs book stands as the most informed account of that dark time. Having been born less than twenty years after the events, and raised on a frontier homestead not far from the site of the final massacres, Sandoz was in a perfect position to tell the story. As a child she listened to the Cheyenne survivors who often stopped by her fathers place to talk. As a professional writer later in life she conducted extensive interviews with the Northern Cheyenne people and spent over a decade researching the historical record for details of the story.

In 1930, before she had gained wide recognition as a writer, the thirty-four-year-old Sandoz and a friend spent three weeks driving a Model T through the Dakotas, Wyoming, and Montana. Her friend was interested in anthropology, and Sandoz saw the trip as a way to generate ideas for new writing projects. In particular, Sandoz wanted more information about the events of 187879 and the slaughter at Fort Robinson. She visited the Northern Cheyenne Reservation and spent several days talking to old-timers who had been part of the exodus. She took extensive notes but made no transcript of her interviews.

By 1936 Sandozs first book, Old Jules (a biography of her complex and sometimes difficult father), was gaining fame and being more widely read. The books financial success allowed Sandoz to begin work on the Cheyenne story. She returned to the Northern Cheyenne Reservation to conduct more interviews and continue her research of archival records. She began writing a manuscript she initially called Flight to the North while living in her New York City apartment.

In 1940 Sandoz was forced to set aside the project when she learned that a competing publisher was about to release a new Howard Fast novel based on the incidents. After World War II and several intervening writing projects, she finally returned to her Cheyenne book. She once again visited the reservation and other key locations of the story, trampling over prairie, rimrock, and badlands, manuscript in hand. According to Sandozs biographer, Helen Stauffer, by that point Sandoz had gathered so much information about the Cheyennes that every square inch of her Greenwich Village apartment was filled with research materials. The only spot not covered with boxes and files was the kitchen sink, Stauffer wrote (174). When some of the original archival material was later lost in a fire, the importance of Sandozs work became clear. Because she had talked to survivors of the ordeal and had kept notes based on missing documents, she knew that her book contained information that could be found nowhere else. She said that, good or bad, her writing was unique in the field and that those who came after her would have to depend upon it (Nicoll 36).

Next page