Books by Mari Sandoz published by

The University of Nebraska Press

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Beaver Men: Spearheads of Empire

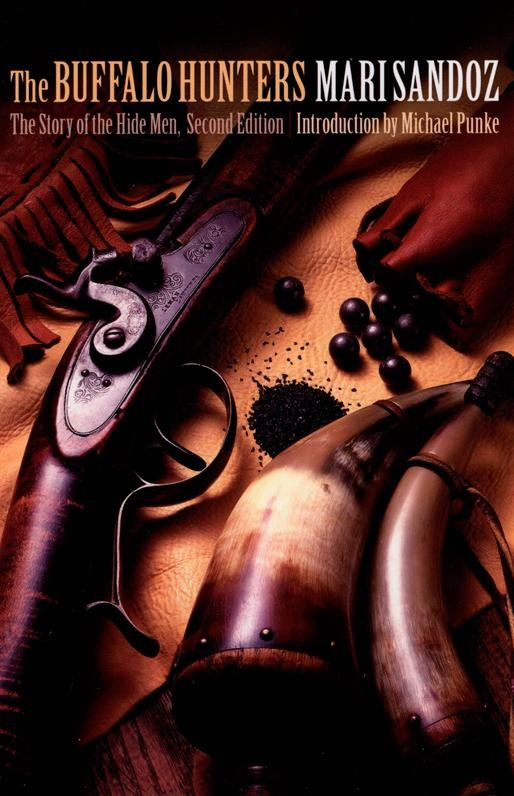

The Buffalo Hunters: The Story of the Hide Men

Capital City

The Cattlemen: From tCrazy Horse: The Strange Mhe Rio Grande across the Far Marias

Cheyenne Autumn

The Christmas of the Phonograph Records

Crazy Horse: The Strange Man of the Oglalas

The Horsecatcher

Hostiles and Friendlies: Selected Short Writings of Mari Sandoz

Letters of Mari Sandoz

Love Song to the Plains

Miss Morissa: Doctor of the Gold Trail

Old Jules

Old Jules Country

Sandhill Sundays and Other Recollections

Slogum House

Son of the Gamblin' Man: The Youth of an Artist

The Story Catcher

These Were the Sioux

The Tom-Walker

Winter Thunder

1954 by Mari Sandoz

Introduction 2008 by the Board of Regents of the

University of Nebraska

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Nebraska paperback printing: 1978

Reprinted by arrangement with the Estate of Mari

Sandoz, represented by Mcintosh and Otis, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sandoz, Mari, 1896-1966.

The buffalo hunters: the story of the hide men / Mali Sandoz; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Michael Punke.2nd ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-8032-4377-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Frontier and pioneer lifeWest (U.S.) 2. American bison huntingHistory 19th century. 3. HuntersWest (U.S.)History19th century. 1. PioneersWest (U.S.)History19th century. 5. Indians of North AmericaWest (U.S.)History19th century. 6. West (U.S.)History1860-1890. 7. West (U.S.)Environmental conditions. I. Title.

F594.S25 2008

978'.02dc22

2008036738

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8032-4600-3

INTRODUCTION

Michael Punke

W hy read history? Why, in particular, read history from a book first published when Dwight D. Eisenhower was president? History, by definition, gives us stories of the past. When well told, the truth of nonfiction trumps the fantasy of fiction every time because, quite simply, it happened. History also helps to explain the present, tracing the lineage of our contemporary world like a collective genealogy. But most profound of all is history's potential to shape the future. In our past lies the potential for wisdom. If heedful of history's lessons, modem society has die opportunity to avoid the toil, error, and blood of history's greatest calamities.

It is in all these aspects that The Buffalo Hunters, die 1954 work of Maii Sandoz, remains so vibrantand vitalfor readers today.

As a starting point, The Buffalo Hunters is a damn entertaining read. Sandoz was decades ahead of her time in recognizing the potential of narrative nonfiction, presenting history not as a dry recitation of chronological facts but as the living, breathing, bleeding stories of the people who acted out historical drama. To paraphrase a line attributed to Wallace Stegner, "the West is America, only more so," and Sandoz understood that the history of the West contains vivid versions of quintessential American diemes: freedom, conquest, work, hope, faith. Sandoz found her inspiration in such compelling topics as the fur trade, the Batde of the Little Bighorn, Crazy Horse, the cattle industry, and the great tribal histories of the Cheyennes and the Sioux. Bringing history to life is San-doz's achievement, above all.

In The Buffalo Hunters Sandoz carries her story with a cast as gripping as any Hollywood feature. We travel along with characters including Wild Bill Hickok, Buffalo Bill Cody, and Lonesome Charlie Reynolds. Yet it is the Native Americans who play the central role. Sandoz understood that the fate of the buffalo and the fate of the Indians were not two stories but one, and here she weaves them together in a great American tragedy.

The relevance of The Buffalo Hunters to our world today is difficult to overstate. We live in an era of monumental environmental challenge, and it is impossible to study the buffalo's destruction without contemplating the excesses of our own generation. In 1867 few grasped the notion that buffalo might be wiped from the face of the planet, and yet in the space of less than two decades, they would be almost gone. The lessons of history, it is worth noting, stood available in those years before the buffalo were destroyed. America, for example, had witnessed the trapping of beavers into near extinction in the 1830s (saved only by a fortuitous change in fashion). It even had specific experience with the buffalo. At the time of Columbus, an estimated two million buffalo roamed the eastern half of the continent; by 1800 encroaching civilization had extirpated them all.

Today we confront our own incredible proposition: human activities are changing the planet's climate, with consequences far beyond the destruction of a single species. The question is whether our generation will heed the lessons of history, none more powerful than the destruction of the buffalo. Will industry act to limit itself, or will it harvest and consume beyond the planet's ability for renewal? Will government, in the absence of such industrial restraint, step in to rein back (or incentivize) the market? Perhaps most critical of all (because it reflects the decisions that each of us control directly): will individuals retreat behind the false notion that the acts of one person make no difference in the broad sweep of global affairs? The Buffalo Hunters, a book about the past, does not answer these questions about the future. But its powerful lessons inform them.

Sandoz, who lived from 1896 to 1966, was a product of the buffalo prairie of Nebraska. Her own story reads like a novel, and the focal point of her life was writing. She pursued it, single-mindedly, against obstacles including a threadbare formal education, a father who considered writers the "maggots of society," a broken marriage, poverty, and the Great Depression. After finally succeeding in publishing her work, she found rejection from her home state, whose residents were not yet ready for Sandoz's unvarnished view of western history. Perhaps it should not surprise us that her books, forged in the furnace of such adversity, stand up to the test of time. We can all be grateful that they do.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

T HE buffalo, the American bison, once roamed most of what is now our nation. Cortez found this creature "with the hump like a camel and hair like a lion's" at Anahauc, deep in Mexico in 1521; others saw buffaloes at the head of navigation of the Potomac in 1621. They had spread into northern Saskatchewan too, and west to the coastal plains. But the region of the buffalo's best adaptation was probably the Great Plains. Here he roamed the open prairies in the vast dark herds that were uncountable, even apparently inestimable, for the estimations varied by tens of millions.

The Great Plains lie between the Rocky Mountains and the bend of the Missouri out of Dakota and reach like a great awkward thumb from Canada down as far as the Pecos, deep in Texas. This region is half the size of all the United States lying east of the Mississippi. It is cut by a succession of east-flowing streams, like a vast, many-runged ladder that the buffaloes climbed northward in the spring and descended in the fall, moving from water to water.

Other animal life had found what is now the Great Plains very compatible, at least for a time. The reptilian monsters, the dinosaurs, had lived here, the big horned