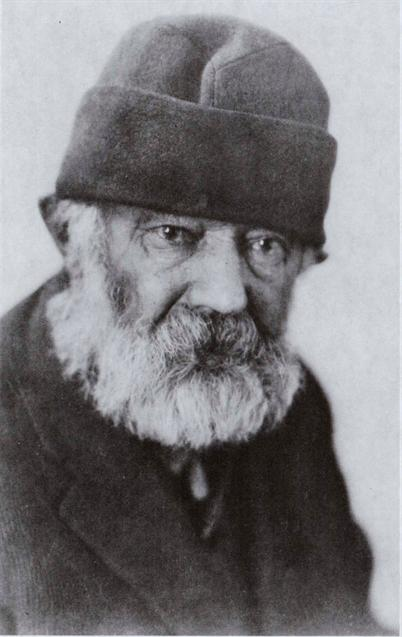

Old Jules. Courtesy of the Estate of Mari Sandoz.

1935, 1963 by Mari Sandoz

Introduction 2005 by Linda M. Hasselstrom

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Bison Books printing: 1962

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

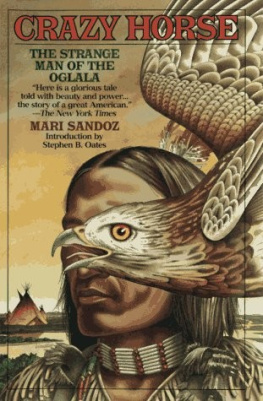

Sandoz, Mari, 18961966.

Old Jules / Mari Sandoz; introduction to the Bison Books edition by Linda

M. Hasselstrom.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York: Hastings House, 1935.

ISBN 978-0-8032-9359-5 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Sandoz, Jules Ami, 1857?1928. 2. Sandoz, Mari, 18961966Family. 3. PioneersNebraskaBiography. 4. Frontier and pioneer lifeNebraska.5. FathersNebraskaBiography. 6. Frontier and pioneer lifeNebraskaSandhills. 7. NebraskaBiography. 8. Sandhills (Neb.)Social life andcustoms. 9. Sandhills (Neb.)Biography. I. Title.

F666.S34 2005

978.2'031 '0922dc22 2004023021

Bison Books Edition reprinted by arrangement with the estate of Mari Sandoz

E-book ISBN: 978-0-8032-9364-9

Linda M. Hasselstrom

OLD JULES AND THE MAGGOTS OF SOCIETY

You know I consider writers and artists the maggots of society.

Jules Sandoz to Mari Sandoz, 1926

Once when a poet friend visited me on the ranch, we naturally talked about our writing. Visiting with my parents, we chatted at length about the importance of writers in society. Finally, my friend said, "It's hard work sitting under a tree writing a poem."

I remember bracing myself for a viciously sarcastic remark from my father, but I can no longer remember what he said. For years afterward, however, he sneered as he quoted my friend's remark to laughing neighbors. Many of those hard-working ranchers believed attending college, reading books, or creating art was a luxury no working family could afford. They proudly said they hadn't read a book since grade school.

My father always remembered my friend's name, and every year or so asked about her. I'd answer honestly: She'd won a National Endowment for the Arts grant. She'd published a book.

He'd grimace and say, "So she's living off the government. Has she got a job? Is she married, or is she still looking for a man?"

No matter what I said, he'd add, "Maybe she ought to spend less time sitting under trees writing poetry."

When I announced she'd gotten married and started having children, he smirked. "Once she starts having babies, she'll be too busy changing diapers to sit under a tree and write poetry. She's going to find out what real work is."

And every time we spoke about her, he'd conclude, "You know, Old Jules had it right when he said writers and artists are the maggots of society."

People who are disturbed by Old Jules forget that only the strong and the ruthless stayedthat the squeamish may be nicer to live with, but they conquer no wilderness. If you look into history you will find that vision is always accompanied by a degree of thoughtlessness, impatience, and even intolerance for others.

Maggotslegless soft-bodied, wormlike fly larvaedevelop quickly in dead flesh and become annoying houseflies and bluebottles. Most rural children could tell firsthand maggot stories, so Jules used familiar facts for his insulting metaphor.

Yet both Jules and my father, John, taught their daughters how to make wise decisions about the land and animals that were our responsibility. The way our fathers treated us contradicted that degrading judgment. Jules's daughter worked hard to become a respected writer and historian. She never willingly compromised her own high standards, never backed down from a battle with anyone who disagreed with her. She survived blizzards, prairie fires, an apartment-house fire, rattlesnakes, argumentative editors, critics, bad reviews, death threats, and every crisis in her life but the last. Nearing the end of her fight to snatch more writing time from the cancer that was killing her, she wrote briskly and without pretense, "After two malignancies one learns to be prepared for anything, and promises very little for the future. If I'm alive I'll be happy to write the introduction for the book." She finished the introduction, though it was published posthumously. Anything but soft-bodied, that Mari.

As Mari contemplated, and quoted, her father's remark about the maggots in later years, I wonder if she thought of that epic story of the trapper Hugh Glass, left to die on the Dakota prairie by his so-called friends after being clawed by a grizzly. She knew Frederick Manfred, apparently admired his writing, and doubtless read Lord Grizzly, his fictionalized account of the ordeal. As Manfred tells it. Glass crawled toward civilization in the stench of his own decaying flesh as the wounds on his back began to rot. Maggots ate the putrid meat, so by the time Glass could stand upright and think of revenge, his back had healed. The maggots clearly did him more good than harm.

Moreover, maggots transform themselves; they change from wiggling grubs to creatures able to see in all directions and travel freely. Jules meant his comment as criticism, but a careful look at the metaphor suggests his daughter might have been justified in taking it as a compliment.

Oh, by the way, you would hardly expect anyone of my temperament to "emphasize the hopelessness of the struggle in the sandhills." I don't recognize any hopelessness in any struggle with nature. Defeated we are, of course, for death is inevitable, but to the people that seem interesting to me the struggle is a magnificent one in any event.

My father may have introduced me to Old Jules; he admired the book as an accurate portrayal of the homesteading era. Yet he became so angry when I wrote about him that he stopped reading my books. (Having learned from him to be stubborn. I buried the books with him.) His Swedish father came to the plains of South Dakota in 1899, homesteading in western South Dakota only a couple decades after Jules Sandoz settled in western Nebraska. When we were trying to solve a problem, my father sometimes wondered aloud what Old Jules would do. He declared that Old Jules knew how to raise children tough enough for real life. Though he never struck me, I was terrified of his cold disapproval. Like Mari, I was "too frightened of him to voice either approval or surprise" at his actions.

My life in Dakota in the 1950s and 1960s was easier than Mari's in Nebraska fifty years earlier. Still our experiences were similar in many ways. We both rode through blizzards, handled and were hurt by horses and cattle, harvested hay and crops. Like Mari I learned how to work hard while discovering the limits of my strength and intelligence. We grew up physically strong, becoming self-reliant women who trusted our own judgment. My father always told me I could do anything I set my mind to do. While he may have taken this philosophical position by defaulthe had no sonsthe effect was liberating. Jules and John treated their daughters like equals: like men.

You know my notions about us human beings. I figger that this world runs on a pretty even keel and those of us who are cursed with fine virtues, like courage and sincerity, have faults as strong. Frontiersmen had to have courage, tenacity, resourcefulness, and determination and the sap of life in superlative degree or they'd high-tailed it back east long before they got to be frontiersmen. To balance these virtues you and your kind are permitted any faults you may care to entertain and it's all right with me.