F OR MY PARENTS ,

F RANK AND M ARY M ORRIS ,

A ND

I N MEMORY OF

MY BABY SISTER , M ARY K ATE

Chapter One

F or months I had wished and wished the baby would be a girl, a little sister. Maybe I shouldnt have wished so hard. A boy might have lived.

Werent wishes kind of like prayers? Maybe my wishing really did make things worse. I knew that didnt make sense, but nothing in this whole terrible day made sense.

Grandma closed the front door with a bang, as if announcing the end of a chapter in a book about our lives. What a day, she said, dropping her purse to the floor. Im going to lie down. You should take a nap, too, Annie. None of us got much sleep last night. Grandma headed to her room, not waiting for an answer.

A nap? I was almost eleven. I hadnt taken a nap for as long as I could remember. Besides, how could a nap change the way we all felt? Wed still wake up. It would all still be the same.

She means well, Annie, Grandpa said. Were all worn out. He looked like he wanted to say something more. I waited. Grandpa had grown older, just in this one day. His glasses were smudged, and his mouth and shoulders sagged. Gray stubble covered his chin.

I thought Grandpa reached out to smooth my hair. We all thought it would be okay this time. Another pause as he started down the basement stairs to his workshop. She had red hair, you know. Very much like yours. A downy, reddish cap.

My baby sister had red hair like mine. If only I could have seen her, just once.

The house was silent. I walked from room to room with that heavy, tired feeling you have after youve cried for a long time. I looked out the windows. How could the sun still shine like it was just any normal day? The kitchen clock showed that it was only 2:45. Maybe Id go down to the Millers. If the Miller kids didnt know about the baby, I could pretend things were normal.

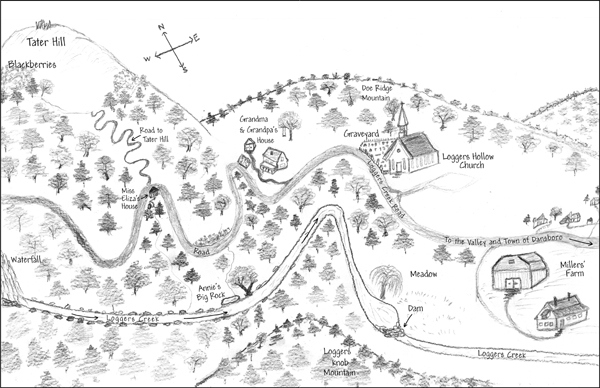

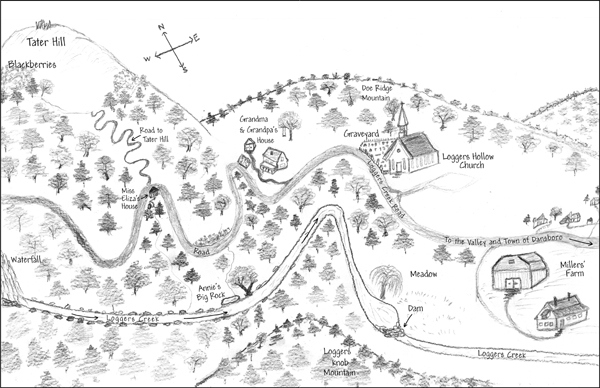

The walk down the winding dirt road to the Millers farm seemed longer than ever before. Maybe it was because I usually ran down and didnt even notice passing Loggers Hollow Church with its small fenced-in graveyard. But this time that little graveyard was all I could think about. I wont look, I wont look, I repeated over and over to myself, but it didnt keep the vision of gravestones out of my mind. Soon my little sister would have a gravestone of her own with her short, one-day life carved into it. Born July 13, 1963. Died July 14, 1963. Grandpa had buried her there earlier this morningall by himself while Grandma and I stayed with Mama at the hospital.

Arent we having a funeral? I had asked.

Grandma was quick to shush me. Were trying to make it easier for your mama. Less for her to go through, she whispered, while Mama lay in bed with her eyes closed, looking like she was asleep. But I could see tears slipping through the cracks and sliding over Mamas face, soaking the pillow beneath her head. Grandma patted her hand, and I tried squeezing Mamas other hand, but she didnt squeeze back.

Easier? Nothing could make things easier right nowexcept if I were miles and miles across the ocean in Germany with Daddy, who didnt even know anything was wrong. This was probably something I should write down in the journal Daddy had given me before he left. Something I should tell him about my summer, but I didnt know if I could ever write this feeling down on paper.

After another curve in the road, the Millers brick farmhouse was in sight, and the yard was spilling over with grandchildren. They lived in their own houses nearby, but today was Sunday. I knew they were all there for the big Sunday dinner old Mrs. Miller always cooked with the help of the four younger Mrs. Millers. If it wasnt raining, they set up long tables in the yard under the shade tree and carried out platters of ham and biscuits, cole slaw, sliced tomatoes, corn on the cobmore food than even all those people could eat. And there would be a fluffy coconut cake that Bobbys mother, the young Mrs. Miller with black hair, liked to bake. After I scraped those tiny flakes of coconut off the frosting, it sure tasted good.

Whichever Mrs. Miller was closest would always set one more plate for me if I was around. I slipped in like I belonged there, just another member of their overflowing family, from crawling babies all the way up to the three older teenagers, who werent around so much now. The only not-so-good parts were old Mr. Miller spitting his brown tobacco juice on the groundonce right next to my footand all the buzzing flies that flew straight from the cows in the meadow to the food on our plates.

By now their Sunday dinner would be over, but it looked like all the kids were playing dodgeball, including Bobby. He was twelve and only a year older than mekind of like the big brother I never had. His curly black hair, just like his mamas, stood out above the heads of all his cousins and younger brothers and sister. Why couldnt I have all those brothers and sisters? At least a few cousins or just one sister. Someone to have fun with, but also to have around during sad times like this. Someone to share this emptiness.

By the time I reached them, I could tell the kids already knew about the baby by the way they didnt look me straight in the faceeven Bobby. The same way I couldnt quite look into Mamas eyes when I first walked into the hospital room that morning. They had stopped playing ball and stood in the driveway, kicking stones around in the dirt.

Finally Caroline, Bobbys nine-year-old cousin, asked, Did you get to see the baby?

I shook my head, not trusting my voice.

Silence stretched on until Bobbys little sister, Ruthie, asked, What was her name?

It took a few seconds before I could get the words out. Mary Kate. There. Id said it out loud, but my voice shook and I could feel my face turning red, the way it always did when I was about to cry. Why had I come down here? What was I supposed to say? This was worse than staying in the house.

Bobby cleared his throat and said, Lets go swing on the rope. Its the last day the barnll be empty. Papaw said were making hay tomorrow.

My breath whooshed out. I hadnt even realized I was holding it, but now moving and breathing made me feel better, thanks to Bobby.

We all ran to the barn and one by one climbed up the ladder to the loft. Usually I had to wait for my turn, but Bobby took the rope from its hook and announced, Annie gets to go first. He handed it to me.

There was no time to gather the courage for that first step off the wood ledge. I gripped the rope before I could think about it, sucked in my breath as if I were jumping into the deep end of a swimming pool, and plunged down. For a second my legs thrashed around in the air until I managed to settle myself on the big knot, and I swept across the wide open space of the barn and up again to the other side. With one hand, I reached out to touch the far wall before swinging back to the loft. Bobby pushed me again, and I flew like a bird soaring across a field. Not a hawk or an eaglemore like a barn swallow that swooped through the sky, one so light nothing heavy or sad could pull me down to earth. I knew the other kids were waiting for a turn, but I pretended I didnt see them. If I kept on swinging, I wouldnt have to think.