First published in 1997 by

FRANK CASS & CO. LTD.

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

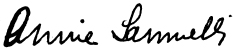

Copyright 1997 Annie Samuelli

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Samuelli, Annie

Woman Behind Bars in Romania. New ed

I. Title

365.4092

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Samuelli, Annie.

[Wall between]

Woman Behind Bars in Romania/by Annie Samuelli.

p. cm.

Earlier edition published under title: The wall between. 1967.

1. Samuelli, Annie. 2. Women political prisoners--Romania--Biography. I. Title.

HV8964.R7S34 1996

365.45083--dc20

[b]

95-23285

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-714-64217-8 (pbk)

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher.

From 1949 to 1961, I was one of a large community of women held in the political prisons of Communist Romania, all harshly convicted, not for their misdeeds but for what they actually represented.

Since the advent of Communism, citizens who upheld faith, justice and the principles of democracyfrom former prime ministers to simple peasants and confused members of the working classnow were convicted of treasonable activities on just those grounds.

The elementary freedoms of opinion, speech, movement, religion and charity, hemmed in by arbitrary government decrees, had been virtually abolished, any transgression being paid for by long imprisonment.

Persecution was directed as much against the aristocracy and bourgeoisie, ostensibly the chief targets of class warfare, as against any person, irrespective of origin, who consciously or not expressed criticism or the slightest opposition to the regime. For instance, spouses, parents, children were likewise incriminated as accessories after the fact, and whole families went to prison for having failed to denounce or for having harboured a fugitive from justice for his political beliefs or for violating one of the all-embracing Communist laws.

Thus the womens prisons were filled with representatives from all ranks of society, from the intellectual down to the illiterate. As I shared their lives day by day, night by night for twelve years, I had the opportunity of studying them closely, and it is mainly on them that this book is based.

Therefore, it is neither an autobiography nor a description of Communist political prisonsformer prisoners, now in the West, have already done it in a masterly fashion. What I wish to show is that under conditions aimed at their gradual physical and mental extermination, this community of women never acknowledged defeat. Neither did the men, but that is their story.

My stories are intended to depict the psychological reactions of women of clashing generations, nationalities, classes and creeds who, herded against a common background of years of captivity under constant fear, united in the dogged determination to survive. We sought and found the means to dilute, if only for minutes, the unceasing hell of life in prison. For to live in fear for twelve years is hell indeed.

Fear in various forms haunted us, haunted me. At the prescribed hour of 10 P.M. I fell asleep with the fear of a rudely interrupted night, awoke with fear at 5 A.M., when a minutes delay spelled brutal punishment. Fear of our ever-present oppressors, our jailers, was the strongest; each flick of the peep-hole lid, each opening of the door, any apparition of a strange officer, any unusual order struck panic in the most hardened veterans like myself.

But this constant, corrosive fear was fought, and in the battle waged against it, another predominant fear was our main weapon: the fear of failing to survive until the next minute, the next hour, the next day, which might unexpectedly bring liberty and all we had come to realize it meant.

While we froze in winter and suffocated in summer, this fear bred the will to overcome starvation by filling shrunken stomachs with the repulsively monotonous empty soups, choking over the cubes of polenta* made from corn and its ground cobs, heroically swallowing the offals that were our weekly meat ration, revelling in our daily thin slice of bitter brown bread and tea-spoonful of unsweetened jam. We knew that if we didnt, our bodies would force us into surrender. As imagination ceased functioning, we did not recoil in disgust from the nauseating contents of the chipped tin bowls; they were but the fuel required to maintain the flame of life, nothing else mattered. And to make up for it, the recital of tasty, mouth-watering recipes fed unsated appetites.

Mental starvation induced by enforced idleness, the Communist interpretation of penal servitude, was as bad as the physical. It bred the fear of insanity. And not even decades in prison could resign us to that evil.

Female ingenuity found substitutes for needles to keep hands busy, while the pursuit of culture became an obsession. Although speaking a foreign language was severely punished, our cell soon turned into a Tower of Babel. French, German, Russian, Hungarian and the prime favorite, English, the language of our presumed liberators, were assiduously studied while we dutifully sat on the backless wooden benches. To rest or sleep during the seventeen-hour day was forbidden. In the impossibility of writing them, as the respective implements in any shape or form were banned, the lessons were soundlessly, endlessly memorized.

At first it was difficult, but our brains rapidly adapted themselves to assimilating lengthy foreign poems and texts of prose verbatim and effortlessly. This attainment, our greatest pride, boomeranged against us later. When my sister and Ijust like other prisoners didfinally entered a world where bookshops, public libraries, theatres and films were accessible, the desire to take advantage of them had shrivelled up. Only the frenzied wish to catch up with the daily concerns of the Western man-in-the-street forced us to exert will-power in order to read newspapers and magazines. But we did not know then that this would be the result, and the exact recollection of what we heard and learned stood us in good stead at the time.

There were periods when even the boon of study was denied me. During seven-day spells in isolation cells, during the frequent transfers from the base penitentiary to the seclusion of prisons of enquiry or to the extra hardships of the underground transit prison nicknamed the Damp Place, I had to find other means of escaping from the inevitable surfacing of the agony of anxiety about my dear ones and from the urge for freedom that would madden me.