Praise forJonestown

Tough and impassioned... this is a finely written and sparkling book. Bridget Griffen-Foley, Sydney Morning Herald

Masters unveils a richly detailed and surprisingly rounded portrait of Jones... the account of how Jones wields and abuses his power as a broadcaster makes for profoundly disturbing reading. Matthew Ricketson, The Age

... a textbook example of how to write a biography of a public figure and a fascinating, compulsively readable account of not just a man but also a city. Herald Sun

Masters account of the abuse of political power is startling. Mike Carlton, Sydney Morning Herald

Chris Masters had done extensive research and the result is a compelling story of the rise and rise of Alan Jones. Newcastle Herald

... an extraordinarily well-written, well-research biography. Illawarra Mercury

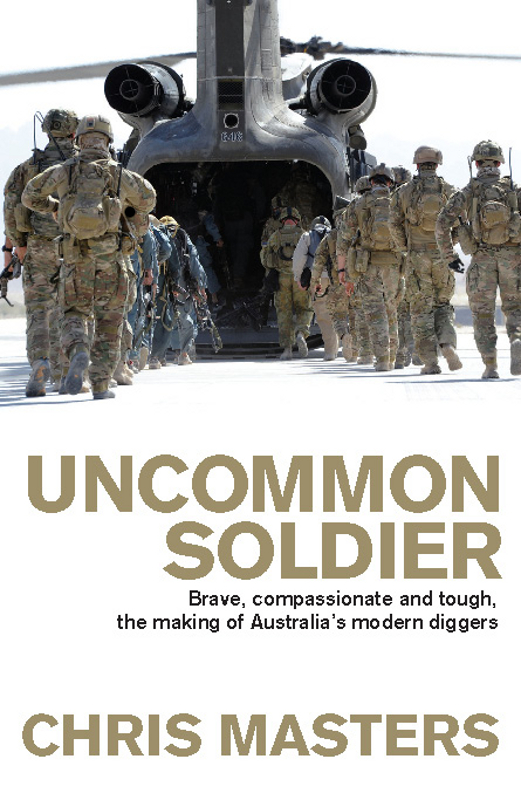

UNCOMMON

SOLDIER

For Tanya

UNCOMMON

SOLDIER

Brave, compassionate and tough,

the making of Australias modern diggers

CHRIS MASTERS

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the

Australia Council for the Arts, its funding advisory body.

First published in Australia in 2012

Copyright Chris Masters 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland, London

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available from the

National Library of Australia

www.trove.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74175 971 6

Typeset in 12/16pt Adobe Caslon by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

The question of what is special about the Australian soldier settled into my consciousness from the time I could think and read. I grew up after World War II in the period of silence that followed the thunder, one among a vast crowd standing beyond the hunched circle of experience. Grandparents and parents exhausted by two wars were sick of talking about it; they were counselled not to, they were brutalised, ashamed, haunted and proud. The frosted glass door the war generations slammed on the subject compelled in me a sharpening of concentration and interest.

Some of my first reading included yellowing copies of wartime yearbooks found in Australian homes of that era: Khaki and Green, Jungle Warfare and the like. Gathered down from the bookshelf and carried to a patch of sunlight on the verandah, I would soak in the images of lean, tough, sun-tanned soldiers who as far as I could tell could not be mistaken for anything but Australian. Sometimes these men would be bearing weapons and a look of serious business. Sometimes they would be laughing, and even showing tenderness if, for example, they were photographed with a wounded mate.

I searched those images for the missing narrative and a keener sense of what really happened. Where was the enemy? What was the joke? How was that soldier wounded? A childish eagerness took on the first rubbings of patriotism.

It was hard to avoid. On the way to school, along the road to the December holiday, I passed the monumentsthey were everywhere. I could not miss the inscriptions, which pressed a deeper groove. A sense of pride formed up alongside nascent notions of service and sacrifice.

I knew the Australian soldiers were volunteers. Like the surf lifesavers who dashed without hesitation to the rescue, the soldiers would return to civilian dress when the job was done. On Anzac Day, when suits were pulled from cupboards, medals pinned and corned beef and pickle sandwiches cut into small triangles, I lined up for more morsels of meaning. If there was boasting I did not hear it. Big noting was not Australian.

By my teenage years I began to hear traces of dissent. George Johnstons book My Brother Jack released some of the ghosts of war. My own uncle Dave, rarely spoken of, had returned from New Guinea a troubled man, a drinker. Alan Seymours play The One Day of the Year challenged the spiritual purity of Anzac; the Vietnam War challenged much more. There was noisy, generational opposition. Australian soldiers were no longer all volunteers. They were again fighting someone elses war, and civilians who were supposed to be protected were being maimed and killed. There was argument that we were not just on the wrong side, we were the wrong side.

I was eligible for the Vietnam draft and would have gone with other conscripts had my number come up. My mother, who worked as a local newspaper reporter, was appalled when I told her. When visiting her I scanned the inevitable home towners, the press releases and photographs sent by the government to local newspapers. They were stories of other local boys, now in uniform, whose exploits had earned a ribbon and a brush with fame. It seems Mums own propaganda had worked wonders.

My number did not come up but I would see war nevertheless, ironically because of Mums influence. By the time I was a young adult it was clear there was no other job for me but journalism, and for me no better place to practise it than the ABCs Four Corners.

At Four Corners a foreign story was often set in a distant war zone, where I would see plenty of soldiers going about their business. It was not always pretty: in Vietnam decades of violence delivered hunger and poverty; in Cambodia the cities were shattered and the country a graveyard; in the former Yugoslavia I saw soldiers on the rampage. Blood and brain tissue on a wall where civilians were slaughtered, ammunition abandoned by the roadside to make space for the looting. In Africa there was starvation born of violence; I watched children die. In Rwanda the bodies were piled higher than the roof of our vehicle. I passed stricken faces and felt I was in hell.

For 25 years I saw cruelty. I saw madness. I saw war. And it made me wonder whether it makes us much the same. Humans will be brave and cowardly; they will use their uniform to protect, and they will use their uniform to pillage. Perhaps soldiers the world over are much the same. The experience of war imposes common characteristics, comradeship (or, as we say, mateship) predominant and also routine, banal expressions of evil.

While I saw plenty that shocked and demoralised me, I cant say the accumulating experience made me a pacifist. Of course it made me anti war, but I am also anti plague and pestilence. There is too much danger out there, too many guns and dark hearts for us to be anything but sensible about protecting ourselves.

Next page