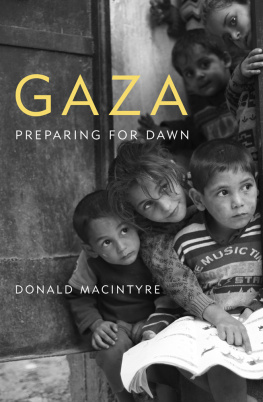

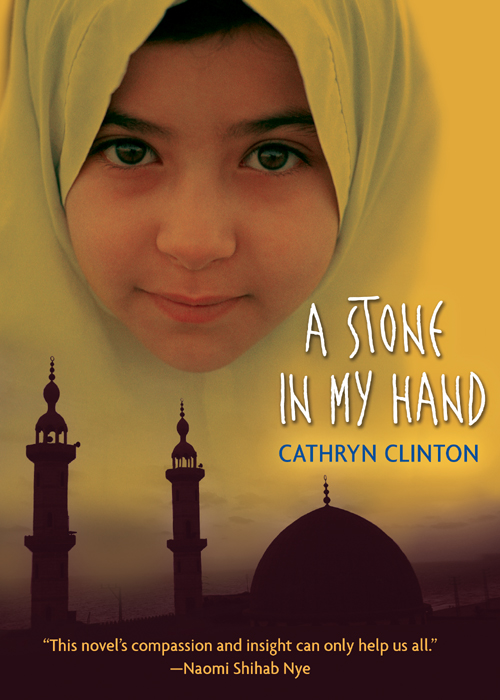

I began writing A Stone in My Hand in 1998, and in January 2000 I signed a contract for the book. It is historical fiction the story of a single girl and a single family and it takes place in Gaza City in 1988 and 1989, when Gaza was under Israeli military occupation. These years were part of the first intifada.

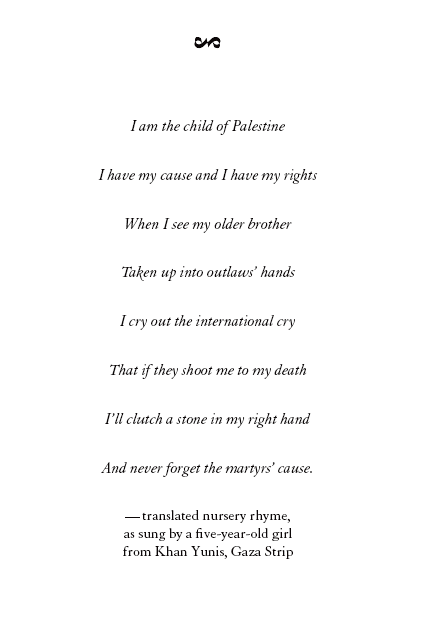

The intifada, which literally means a shaking off, was an unplanned uprising of street demonstrations and strikes by the Palestinian people. The first intifada began in 1987 and ended in 1993. A Stone in My Hand reflects that period of time and is not meant to be a comment on political situations in the Middle East today.

I am Malaak Abed Atieh, and this bird is Abdo. Abdo lives here on the roof. I sneak him seeds when no one is watching. My sister lives in the smell of the stove with my mother, like the other girls I know, but I do not. I live in Abdos eyes. I see things my sister and brother will never see. I fly high, high above Gaza City. I soar out of the Gaza Strip. Nothing stops me, not the concrete and razor wire, not the guns, not the soldiers. I stare at them with my hard black Abdo eyes, and they do not shoot me. I am hidden. I laugh at them, but they dont hear it in the sound of the bird. My wings are strong. I dip and dive, stretching these wings, but then I come back to the roof and fold them under me. Someday I may fly away for good, but for now I watch and wait.

My brother, Hamid, is cocky. He always argues with my sister, me, my mother, everyone. I think that when he was born, his mouth was wide open yelling and his hands were in little fists. Yesterday he and Tariq, his best friend, left to play soccer. I followed Hamid. He is easy to follow because his wiry hair sticks out all over and he walks with a strut, like Abdo. They were only halfway down the street when an Israeli soldier appeared at the corner. They ducked into an alley, then came back out with stones in their hands. They shouted at the soldier and ran toward him. They lifted their arms to throw the stones.

I gasped. They could be arrested for that, beaten even. But the soldier lifted his gun over his head, holding it with two hands, and yelled. Hamid yipped and turned and ran into Tariq. Tariq fell over, twisting his ankle under him. Hamid kept right on running. The soldier started laughing.

I helped Tariq limp home. He stared, unblinking, with his stone eyes. He winced with pain, but he didnt speak to me. I didnt speak to him. We are alike in this: we both speak very little.

Hamid brags about being one of the shabab; he thinks this makes him a youth fighter in the intifada, which was started by the people of Gaza a little over a year ago.

Last night, he said to my sister, The young men of Gaza are tired of standing by the road, hoping for a days job. Waiting, waiting for some Israeli to come up and check our muscles and stare into our eyes. We are not animals. We are shabab.

Hamid shakes his fist as he speaks. I just stare at him. He must have heard those words from someone else.

We are fighters. The stones speak. The soldiers will have to listen. The brave Hamid who left his friend alone in the street. For now, Hamids biggest fist is in his mouth.

My sister, Hend, looks like my mother. Deep dark eyes, thick straight hair, straight nose, and straight teeth. She is pretty.

Im not. My nose is too big, like someone punched it in. Probably Hamid did. One front tooth overlaps the other. I dont have straight anything. And my wavy hair flies around my face.

Hend thinks of marriage, and little-beard boy-men. A few months ago when we were on the way to the market, she said, I will have a wedding bigger than any you have seen.

I laughed. When, Hend?

When the intifada is over; you wait and see, she said. Since the intifada started, there havent been wedding celebrations in Gaza. How can we have wedding celebrations, my mother says, when there have been so many funerals?

Hamid says, Will you be rich, Hend?

When this trouble is over, this uprising, well have the money. You wait and see, she replies. Hend, the wait-and-see girl.

Hamid laughs and laughs. Hends breath escapes in a hiss. Why do I even bother to tell you anything? What do either of you know? You are just foolish children.

Who is foolish? I am a girl, but I do not hope for men. I do not wait for weddings. I am not content with cooking and sighs. I go to the roof. I live in Abdos eyes. I see things my sister and brother will never see. I live in the sky.

Malaak, come down. I pretend that I do not hear my mothers voice. Malaak, I know you are there. She will come up on the roof if I am quiet. Her thump, thump climbs to me.

She sits beside me, arm around my shoulder. Her eyes become full. Full of salty water like the sea. The Dead Sea. I do not look into them. Instead I kiss the salt on her cheeks. We are sitting in the same place where we sat a month ago when we watched my father walk away.

That day, he was going to look for mechanic work in Israel because he had just lost his job. The garage owner said there were not many cars in Gaza to fix anymore because so many wealthy families had emigrated to other places since the intifada. But my mother works too, and theyre saving money to buy a taxi.

Right before the corner, Father turned around and gave me the signal. He shot his fist into the air with his thumb pointed up. This sign means I am winning. Then he yelled, See you there in the evening.

I laughed. This meant that even a job in Israel wouldnt change our game. Ever since I was little, I would wait on the roof for my father to come home from work. When I saw him at the corner, Id make the I-am-winning sign. Then Id run down the roof stairs on the back outside wall of the house, and in through the kitchen door. Father would race through the street. Whoever got to the front door first was the winner. Usually I won.

That day, my mother and I stared until we saw him no longer. We have not seen him since.

How is Abdo? she says. Others would be rid of him by now. But my mother knows Abdo is special. She doesnt touch him.

I hold out my hand, palm up. I place a seed in it. Abdo flies into my palm and pecks it without touching my skin. We look into each others eyes. Then he flies to my shoulder and sits there.

He is strong, my mother says. We go downstairs to eat together. She is very quiet. She doesnt speak the rest of the evening. She kisses me on the forehead.

Sleep, my child. My mother presses my forearm with her hand. I lie down on my mattress and turn toward the wall. Sleep comes quickly.

A rooster wakes me. Or is it the voice of the muezzin, calling from the mosque, for morning prayer? They crow at the same time. They fight over who gets to wake the people. Today, the rooster won, so I get up before Hend does. She gets up for morning prayer.

When I climb to the roof to feed Abdo, I hear the