The Least of All Possible Evils

Humanitarian Violence from Arendt to Gaza

EYAL WEIZMAN

The research for this book was supported by the European Research Council (ERC) project Forensic Architecture and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts

This edition first published by Verso 2011

Eyal Weizman 2011

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the images in this book. Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologizes for any omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

Epub: 978-1-78168-062-9.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

For TP and SP, who will know when they grow

Contents

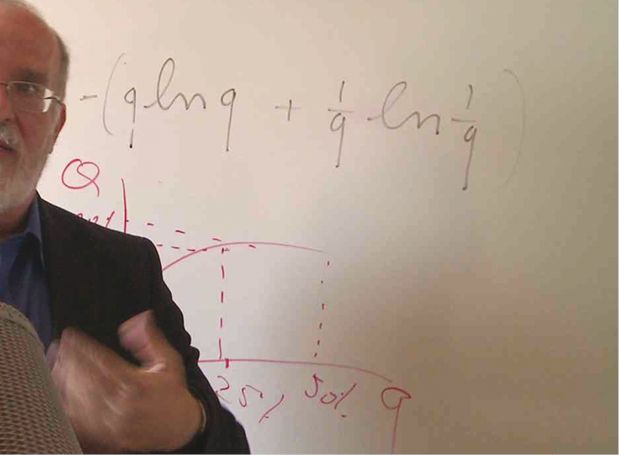

Itzhak Ben Israel explains to Yotam Feldman his mathematical equation for the destruction of Hamas by eliminating (arresting or killing) its operatives. The Lab 2011.

The Humanitarian Present

Having survived the butchery of a gruesome battle, Candide escapes the army and comes upon his long-time tutor Pangloss. The two decide to set out on a sea journey. A tempest wrecks their ship, killing almost all aboard. Pangloss and Candide are washed ashore in Lisbon upon a plank. Hardly do they set foot in the city... than they feel the earth tremble beneath them; a boiling sea rises in the port and shutters the vessels lying at anchor. Great sheets of flames and ash cover the streets and public squares; houses collapse, roofs topple on to foundations, and foundations are levelled in turn; thirty thousand inhabitants without regards to age or sex are crushed beneath the ruins. argues that there is no effect without a cause. He explains to Candide that divine calculations, obscure to the human mind, mean that all that happened is for the very best. For Pangloss, of course, all was always for the best in the best of all possible worlds. Voltaires grotesque satirical adventure novel continues across seas and continents, witnessing the cruelties, violence and destruction of both the human and divine order: from war in Europe through storms and earthquakes to the colonialism of the eighteenth century in the Americas. Indeed across the Atlantic, our two protagonists observe how the Jesuits in Paraguay, claiming to have arrived there to help and redeem the indigenous peoples, actually abuse and enslave them.

Candide was written in the wake of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, tsunami and fire, and in the middle of the Seven Years War, which wreaked havoc across Europe and its American colonies. In the shadow of this catastrophe a new order of urban planning emerged in Lisbon, a gridded geometry that was later exported to the American colonies. The sequence of devastation, described above, prompted Voltaire to challenge and ridicule Leibnizian optimism and with it the concept of necessity, which implies that destructive events somehow serve an invisible and mysterious purpose in a world in which the relationship between good and evil is always optimal. Leibniz himself had been buried two decades when the Lisbon earthquake struck, but it was he who had proposed the scheme of the best of all possible worlds in order to reconcile all the apparent evils in the world floods, starvations, wars, storms, tsunamis, epidemics, pandemics, earthquakes, fires and other phenomena we now like to refer to as emergencies with the idea of divine providence, which is necessarily omnipotent, omniscient and omnibenevolent all-powerful, knowing, and good.

Divine examination, evaluation, calculation and choice operate thus within a complex economy in which good and bad could be transferred and exchanged. Because in this economy all bad things necessarily appear at their minimum possible level, the world as lived is always necessarily the best of all possible worlds. If a lesser evil is relatively good, Leibniz reasoned, so a lesser good is relatively evil... to show that an architect could have done better is to find faults in his work.

If this description of the economy of divine government is already reminiscent of the logic of contemporary wars, with its own scales of risk and proportionality used to evaluate the desired and undesired consequences of military acts, it is hardly surprising to find in it an early reflection on the concept of collateral damage. Earlier Christian theology has indeed already described all bad things that take place as the collateral effects of the good. In this immanent order of human and divine life, the destructive result of floods are nothing but the collateral effect of necessary rain. In both their theological and military contexts, as Giorgio Agamben observed, the collateral effects are structural rather than accidental. It is through the collateral flood or blood that a government divine or human can demonstrate, indeed exercise, its power.

Unlike the calculations of a God, seen by the philosophers and the theologians of the eighteenth century as a perfect mathematician who could undertake instantaneous calculations and immediatly arrive at a precise result, mere humans must of course guess, speculate and hedge their risks as they proceed towards the future as the blind leading the blind. It is for this reason that they ceaselessly seek to develop and perfect all sorts of technologies and techniques that might allow them to calculate the effects of violence and might harness its consequences. It is these techniques and technologies, apparatuses and spatial arrangements, that are at the heart of this book. Through them, Panglosss Leibnizian scheme or is it Leibnizs Panglossian scheme? of the best of all possible worlds re-emerges in the progressive tradition of liberalism. Here, in its secularized form, political rather than metaphysical, a similar structure of the argument sets up the sphere of morality as a set of calculations aimed to approximate the optimum proportion between common goods and necessary evils. But as the general outlook of liberalism shifted from Voltaires and indeed Jeremy Benthams later focus on the greater good and the responsibility of government to increase happiness to the greatest number of people, to the liberal canards of just wars, and their increasingly sophisticated technologies for minimizing the number of necessary corpses, the search for the best of all possible worlds started giving ground to the present neo-Panglossian pessimism of the least of all possible evils.

This book engages with the problem of violence in its moderation and minimization, mostly with state violence that is managed according to a similar economy of calculations and justified as the least possible means. The fundamental point of this book is that the moderation of violence is part of the very logic of violence. Humanitarianism, human rights and international humanitarian law (IHL), when abused by state, supra-state and military action, have become the crucial means by which the economy of violence is calculated and managed. A close reading of a series of case studies will show how, at present, spatial organizations and physical instruments, technical standards, procedures and systems of monitoring the complex humanitarian assemblage that philosopher Adi Ophir called moral technologies have become the means for exercising contemporary violence and for governing the displaced, the enemy and the unwanted. The condition of collusion of these technologies of humanitarianism, human rights and humanitarian law with military and political powers is referred to in this book as the humanitarian present. Within this present condition, all political oppositions are replaced by the elasticity of degrees, negotiations, proportions and balances.

Next page