Table of Contents

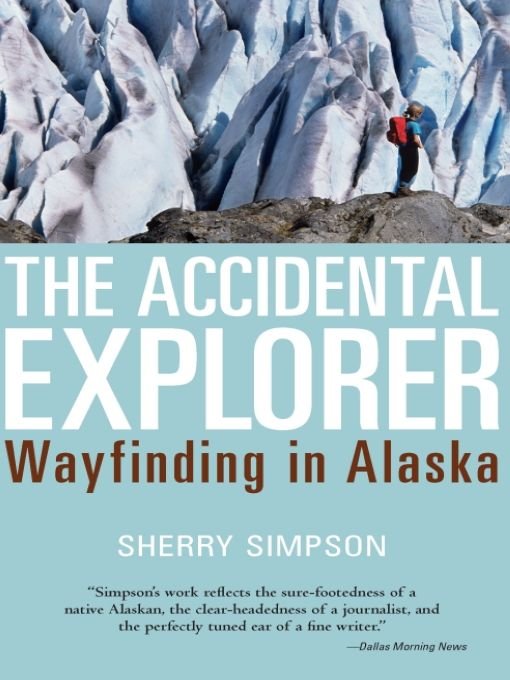

ALSO BY SHERRY SIMPSON

The Way Winter Comes: Alaska Stories

For the first adventurers I ever knew:

Mom, Dad, and Aunt Chris.

And life has thus been searched and exploited almost everywhere all lands over, except: Among us who seek on enchanted rivers an answer to those underthoughts that make life at once a tragic and ecstatic thing, who dare for nothing but the cause of daring, who follow the long trails.

ROBERT DUNN, The Shameless Diary of an Explorer

Introduction

YEARS AGO A SECRET BOOK EXISTED behind the counter of the hotel in Denali National Park. A friend who worked there showed it to me once. The tattered cover read: Official Black Book. Enter all silly questions and other strange things within. For season after season, bemused hotel clerks had recorded unusual inquiries made by park visitors. The book was a compendium of disappointment and confusion, inked in scribbles of various colors and urgency:

What time do you turn on the Northern Lights?

Where do they keep the animals in winter?

Do bears lay eggs?

What do we do on the second day here?

When do they let the animals out?

Is the park open to everybody or just to tourists?

I memorized some of the questions so I could repeat them at parties. It was easy to mock tourists who visited Alaska for a few days and then left, probably forever, never quite certain of what theyd seen and why theyd come. If these questions represented their abiding mysteries, I couldnt imagine what on earth theyd discover here.

How come the mountain is so far away from the park?

Wheres my wife?

How much does Mount McKinley weigh without the snow?

How many undiscovered lakes are there in the park?

But if you dont have radio, TV, telephones, tennis courts, or a swimming pool, what is there to do?

One question haunts me still. The Official Black Book describes an old man who approached the desk to ask, How far do I have to go before I can say Ive been there?

I wish I had been the scribe who, upon hearing his riddle, copied the words in careful script onto the books lined pages before stepping around the counter to take the pilgrims arm. Yes, my friend, Id murmur, leading him gently away. Wouldnt we all like to know?

And together we would push through the hotels double doors and into the unknown world, as if we could discover the answer and return to tell everyone else.

I was born in Santa Fe, New Mexico, as were my father and my sister. Our family moved eleven times before I turned seven. I attended three first grades: in Utah, in Colorado, in Virginia. I remember the July day we arrived in Juneau, Alaska, the way the barnacle must regard its final and lasting attachment, with relief and a niggling worry: Is this the place?

The following summer we lived in Mount McKinley National Park, as it then was known. My father, a civil engineer, was in charge of a project to pave the first fifteen miles of the park road as far as the Savage River. For three months, we lived at park headquarters, a modest compound of log buildings built in 1925 and newer government housing. We wedged ourselves into a trailer so small that the four kids shared two bunks embedded in the hallways like Pullman sleepers. I slept with my sisters feet in my face the entire summer.

How I envied the few children who lived in the park year-round. They schooled at home with their mothers and mailed lessons to a correspondence teacher in Juneau. My friend Julie showed me the picture shed drawn of a lynx that appeared near their house one winter, which her teacher endorsed with an enthusiastic A. Probably it seemed to me that Julie had been graded not on her artistic abilities but on being lucky enough to live in a place where lynxes snowshoed about on furred paws and speared innocent creatures with an amber glance.

Julies older brother knocked together a tiny log cabin on the slope above Rock Creek just beyond the houses. We chinked the gaps between peeling spruce timbers with fragrant moss and tacked flowered fabric across the crudely notched window. I imagined living there through winter, when snow fell so deep it buried the world. Like the romantic I would forever be, the practicalities of making heat and gathering food never occurred to me. In the spring I would burrow out like a bear, blinking in the light.

That summer the sun never set long enough for true darkness to fall, and no matter how tightly we pressed curtains against the porthole in the bunk bed, brightness buckled around the edges as I lay trapped in false twilight, restlessly shoving against my sisters legs. Surely my parents had rules, but in a place without playgrounds or fences or ball fields, its no wonder my strongest memories feature me as an orphaned, half-feral child roaming freely from adventure to adventure, discoveries all around.

This, then, was the child becoming herself. I pounded dull cubes of fools gold free from granite rocks. Dug green bones of snowshoe hares from beneath a duff of dry spruce needles. Chucked arrows at makeshift targets. Felt the blast of my heart when I woke from daydreaming to see an impassive moose standing before me. Heard the drum of my feet against the damp trail as I ran away. Tasted the sour burst of blueberries picked warm and dusty. Scuffed through the silvered ruins of some long-dead prospectors cabin.

This is how I discovered my home. This was my first act of wayfinding.

Sometimes, though, we lose our way, without ever realizing it. The summer in Mount McKinley ended, and my mother drove the station wagon along washboard gravel roads through mountain passes and tundra plains to a ferry that scooped us in and floated us back to Juneau. We lived in the Mendenhall Valley, hedged by a glacier at one end and tidal flats at the other. Year by year, more and more people like us fell like cabbages off a conveyor belt that rolled ceaselessly from the province we called Outside. On this suburban frontier I grew up climbing trees in a rain forest and riding motorcycles on back roads scraped from glacial till. I camped with friends on uninhabited beaches and stood in line for Star Wars, fished with my dad off Shelter Island and played third-string basketball in high school, ate (reluctantly) ocean-bright salmon two or three times a week and Kraft macaroni and cheese when we were lucky.

I never became the sort of Alaskan who flies planes, kills wild animals, fishes open seas, climbs mountains, or treks through the backcountry as if it were no more troublesome than driving to the local 7-Eleven for a newspaper. Nobody I knew then made long, aimless excursions into the backcountry. That would require arranging vacation time, paying dearly for plane charters, and suffering unusual privations and unforeseen difficulties. Such pursuits might have signaled a lack of something more useful to do with your time.

Besides, life seemed interesting enough in a place where the separation between nature and home seemed no more substantial than the faint rattle of a beaded curtain between doorways. Black bears strolled through backyards. Humpback whales coursed silently like intergalactic freighters beneath my fathers boat. The Mendenhall Glacier was a grand blue slab of scenery for thousands of thrilled tourists and a playground where everyday hooligans like me spent afternoons leaping off moraines and plinking rocks at castaway icebergs.