In a bone-chilling drizzle we waded through the swollen waters of the Anaktuvuk River. Two days of steady rain and snowmelt had turned its clear waters a muddy and ominous brown. Somewhere up ahead lay Ernie Pass and the crest of the Brooks Rangethe Arctic Divide. Even in June at the height of the brief Arctic summer, there was evidence everywhere of the brevity of the season and the harshness of the lands extremes.

Clouds obscured the highest peaks, but surely the summit of the pass must be close. For hours we made slow but steady progress across a trailless patchwork of toadstool-shaped tussocks and grassy bogs. That had to be the passright up ahead. The verdict was unanimous except for one lone dissenter. That was the pass, all right, he argued, but it was still four miles and a major drainage awaynot within a hopeful thirty minutes.

A lively discussion consulting topo map and GPS soon confirmed the unpopular position. There were still miles to go. Under a quiet blanket of misty gray clouds, the rest had been lulled into a false hope by the sheer scale of the land itself. Here, one can walk for days and still see major landmarks seemingly unchanged.

Scale. Thats what this land is all about.

When I would mention to those only generally knowledgeable with Alaska and its literature that I was writing a history of that bold land, all too often the response would be, Oh, you mean like James Michener. As a historian and not a novelist, I gradually became upset by this comparison. Closer examination of such responses, however, actually affirmed that I was indeed on the right track. What I was writing was in fact a big picture look at Alaska, and people seemed to understand what that meant.

Now to be sure, there have been many, many books written about Alaska, but fewamong them Micheners noveltell the entire Alaskan story from its first inhabitants to contemporary challenges. Given Alaskas wide-ranging geography, its ubiquitous cast of dynamic characters, and its diverse cultural complexities, such a task is a tall order. There are so many pieces thatjust like a jigsaw puzzleit is impossible to pick up the whole without the pieces falling apart. You can admire the assembled puzzle flat on a table, but it defies handling for close-up examination. Thus, you describe the puzzle in broad terms, all the while striving not to obscure the details of its individual pieces.

But if such a broad view is necessary, why is this entire sweep of eventsthis big picture of Alaskas historyimportant, or even insightful? Alaskas historic themes are surprisingly consistent and reoccurring: new land; new people; new richesand ever-present competing views over their use. These themes have been played out by many different personalities, events, and responses over the years, but to better appreciate their place in the puzzleto get ones hands around the whole story and pick up the puzzlerequires a step backward.

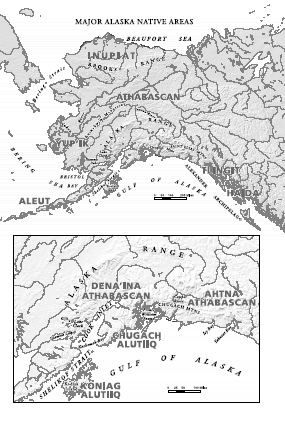

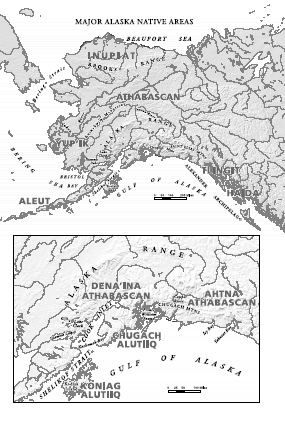

The view that results from such a vantage point is one of a succession of waves crashing across Alaskas landscape: Siberian emigrants crossing the Bering Land Bridge; Russian promyshlenniki (hunters) exploiting a fur empire; European flag bearers checking rival advances; Americans looking north in the aftermath of civil war; argonauts from across the world stampeding north to the clarion summons of gold; soldiers and sailors battling out a decisive chapter in a world war on the most bizarre of battlegrounds; another rush for a different kind of mineral wealth; and always at the core, the conflict over how the land will be used and by whom.

Throughout Alaskas history there has always been another wave cresting, another frontier to cross. Some have wished that the land would remain static, but it never has and never will. Others have been at the vanguard of change, leading the charge to extract tangible resources from its intangible beauty.

Some call Alaska the last frontier. But seen in the full spectrum of its recorded history, that appellation could be applied to any number of periods. It is not so much that Alaska is the last frontier, but rather that it is a land that has always had new frontiers thrust upon it. It is a land that always has been, and always will be, crossing the next frontier.

Raven came, releasing the Sun, Moon, and Stars. His cunning creations, the elders say, changed the world.

T LINGIT ORAL HISTORY

Mountains, Glaciers, and Innumerable Rivers

First Steps, Continuing Traditions

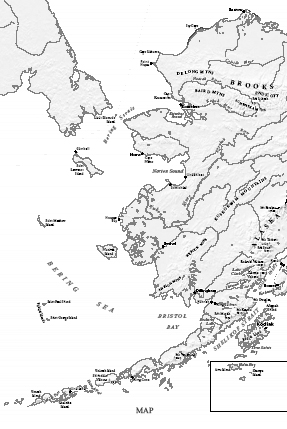

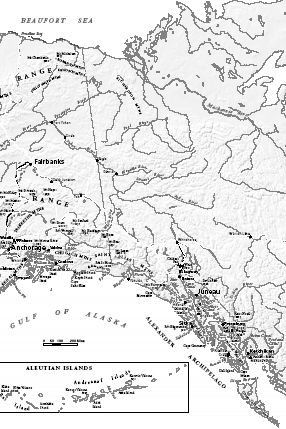

Look at a map of Alaska. What you notice first, and what remains with you long afterward, is the scale. Here is a land where superlatives abound and comparisons are few. Here is a land that dwarfs almost any wilderness you have known: Highest mountain in North AmericaDenali; third longest river system in North Americathe Yukon; largest U.S. national parkWrangellSt. Elias; southernmost tidewater glacier in North AmericaLeConte; northernmost town in the United StatesBarrow; largest U.S. national forestthe Tongass; largest subpolar icefield in the worldBagley Icefield.

Alaska is 615,230 square miles of rugged mountains, grinding glaciers, seemingly endless tundra, broad rivers, and rushing streamslarger than all but seventeen of the worlds countries. Everything that has happened or will happen herefrom the first people migrating from Siberia, to the gold rushes and oil booms, to the competing issues of wilderness versus development everything is inextricably tied to the land. One cannot understand the story without knowing something about the setting and the people who first set foot upon it.

Rivers, creeks, and streams almost without number course through the extent of Alaska, but it is the mountain ranges that most define its landscape. Jutting southward from the main landmass, the Aleutian Range is the backbone of the narrow Alaska Peninsula. To the north, the Alaska Range sprawls more than 500 miles across the heart of the state, rising to 20,320 feet atop the icy crown of North America. The Chugach and WrangellSt. Elias Mountains shadow the Alaska Range to the south and wrap around southcentral Alaskas turbulent rim of fire and ice. Southeast of the St. Elias Range, the Coast Mountains march down the southeast panhandle above the emerald waters of the Inside Passage. West of the Alaska Range, the Kuskokwim Mountains are mere foothills by comparison, but this range rises above the entangled streams and wetlands of the Yukon and Kuskokwim river systems. The Kuskokwim Mountains point north toward the Brooks Range, the northernmost mountain chain in the United States and the roof above Alaskas North Slope.