1812

THE WAR THAT FORGED A NATION

W ALTER R. B ORNEMAN

For my mother

Barbara Lucille Parker Borneman

(19271956)

CONTENTS

The War That Forged a Nation

Drumbeats (18071812)

Bugles (18121814)

Finale (18141815)

At first glance, a history of the War of 1812 may seem to be far afield from my previous writings on western history. In truth, as a youngster growing up in Ohio, I cut my teeth on tales of the American Revolution, the later battles along the Great Lakes, and the settlement of the Northwest Territory. When childhood fascination turned to academic study, I quickly came to realize that whatever happened west of the Mississippi had its roots in the eastern rivers and forests that had first captured my imagination.

My chief goals here are to present a readable history of the War of 1812, place it in the context of Americas development as a nation, and emphasize its importance as a foundation of Americas subsequent westward expansion. Though frequently overlooked between the Revolution and the Civil War, the War of 1812 did indeed span half a continentfrom Mackinac Island to New Orleans and Lake Champlain to Horseshoe Bendand it set the stage for the conquest of the continents other half.

For those who wonder how I could write a history of the War of 1812 based in Colorado, I must thank the Denver Public Library, the Penrose Library of the University of Denver, and the Arthur Lakes Library of the Colorado School of Mines. I am also grateful to the research assistance of Fadra Whyte at the University of Pittsburgh and Christopher Fleitas at Yale University, and the cartographic skills of Eric Janota at National Geographic Maps.

In addition to newspapers and the Annals of Congress, many primary sources from this period are increasingly available in published form. These include the personal papers of such key figures as John Quincy Adams, Burr, Clay, Gallatin, Hamilton, Harrison, Jackson, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, and Wilkinson. John C. Fredriksens War of 1812 Eyewitness Accounts is the key to finding primary sources from lesser-known participants on both sides. Recent publication of The Naval War of 1812: A Documentary History has also placed a host of primary sources at ones fingertips. There have been many scholarly histories of the war or its phases over the years, but one of the most recent and clearly the best is Donald R. Hickeys The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Professor Hickeys insight and voluminous footnotes are a treasure trove and form bedrock for any serious study of the period. Other essential secondary sources include J. Mackay Hitsmans The Incredible War of 1812 from the British and Canadian perspective; Robert Reminis biographies of Jackson and Clay; and Arsene Latours Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana and Robert McAfees History of the Late War in the Western Countryboth published shortly after the conflict. Theodore Roosevelts The Naval War of 1812 and Alfred Thayer Mahans Sea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812 remain steady stalwarts.

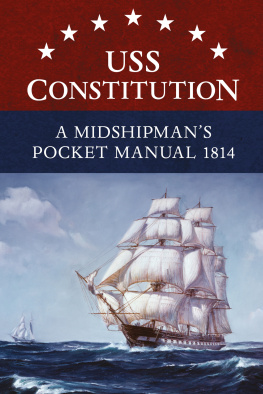

As always, my favorite part of the research was being in the field. My beloved grandparents, Walter and Hazel Borneman, may have started it all by taking me to Brocks Monument at Queenston Heights at the age of four. In ensuing years, I walked the decks of Old Ironsides, looked out across Put-in Bay, visited Presque Isle, and crossed the straits of Mackinac. More recently, my wife, Marlene, and I toured Fort McHenry, Chesapeake Bay, and Lake Champlain. Jim Gehres and Jean McGuey joined us on a whirlwind return to Queenston Heights, Lundys Lane, and Chippawa, and Jim and Gail Fleitas extended us cordial southern hospitality for a reenactment of the Battle of New Orleans. This book makes number two with two of the best, my editor, Hugh Van Dusen, and my agent, Alexander Hoyt. Im very glad to be a part of the team!

In some respects, it was a silly little warfought between creaking sailing ships and inexperienced armies often led by bumbling generals. It featured a tit-for-tat, You burned our capital, so well burn yours, and a legendary battle unknowingly fought after the signing of a peace treaty. In the retrospect of two centuries of American history, however, the War of 1812 stands out as the coming of age of a nation.

In June 1812 a still infant nation of eighteen loosely joined states had the audacity to declare war on the British Empire. Such indignation was fired by resentment over years of British high-handedness on the high seas and envious yearnings by Americans west of the Appalachians for more territory. But a good part of the country, mostly the New England states, thought there was far more to lose by pulling the lions tail than a handful of ships and impressed sailors. New Englanders did not take kindly to or go out of their way to support what they called Mr. Madisons war.

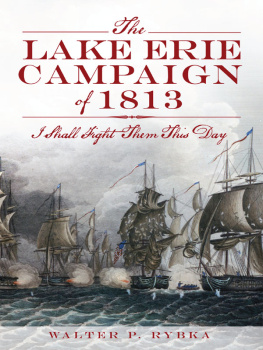

Indeed, Great Britain might have easily crushed the upstarts if it had brought its full weight to bear on the matter, but the British were preoccupied with Napoleons maneuvers in Europe, and the American war in North America remained a sideshow for its first two years. During that time the American navy proved its mettle and found an icon as the USS Constitution, Old Ironsides, sent two first-rate British frigates to the bottom. On land, despite Henry Clays boast that the militia of Kentucky alone was capable of conquering Canada, two years of invasion attempts on three fronts failed. When the tide appeared to turn in Americas favor, it was because a twenty-seven-year-old lieutenant named Oliver Hazard Perry ran a flag boasting Dont Give Up the Ship up his flagships mast and with a motley collection of hastily built ships chased the British navy from Lake Erie.

Within two months of Perrys victory, however, Napoleon met his first waterloo at Leipzig, and victorious Great Britain was free to swing a battle-hardened hand at its American cousins. Suddenly the young American nation was no longer fighting for free trade, sailors rights, and as much of Canada as it could grab, but for its very existence as a nation. In 1814 Great Britain threatened assaults against all corners of the United States: from Canada via Niagara Falls and Lake Champlain, into the heartland of the mid-Atlantic states from Chesapeake Bay, and against that door to half a continent, New Orleans. For a time it looked as if the British Empire might regain its former colonies.

With Washington in flames, only a valiant defense at Fort McHenry saved Baltimore from a similar fate. The greatest American victory in 1814, however, may have come not on the battlefield or the high seas, but at the negotiating table. Somehow, with British armies arrayed along its borders and a British blockade locking up its ports, the United States managed to sign a peace treaty on Christmas Eve, 1814, that preserved its preexisting boundaries, even if it made no reference to one of the wars most egregious causes.

The news of the Treaty of Ghent reached Washington only after Andrew Jackson had assembled a tattered force of army regulars, backwoods militia, and bayou pirates and bested the pride of British regulars. Strategically, the Battle of New Orleans was of no military significance to the war, but politically it came to fill a huge void in the American psychenot only propelling Andrew Jackson to the presidency, but also affirming a strong, new sense of national identity.

During the War of 1812, the United States would cast aside its cloak of colonial adolescence andwith more than a few bumbles along the waystumble forth onto the world stage. After the War of 1812, there was no longer any doubt that the United States of America was a national force to be reckoned with. But in the beginning, all of this was very much in doubt.